Credit: CfA/Melissa Weiss

During a press conference at the 247th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Phoenix, Devesh Nandal from the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian (CfA) and lead author of the study revealed that the universe’s most mysterious distant objects, known as little red dots, may actually be gigantic, short-lived stars.

Before he started the main part of his lecture, Nandal asked his audience a question: “How massive do you think a star can truly get?” He went on to explain how new thinking about the answer to this question was relevant to his team’s discovery.

The team collected data for this study, to be published in The Astrophysical Journal,from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). It shows how the first supermassive black holes may have formed, and goes a long way in helping scientists understand the early universe.

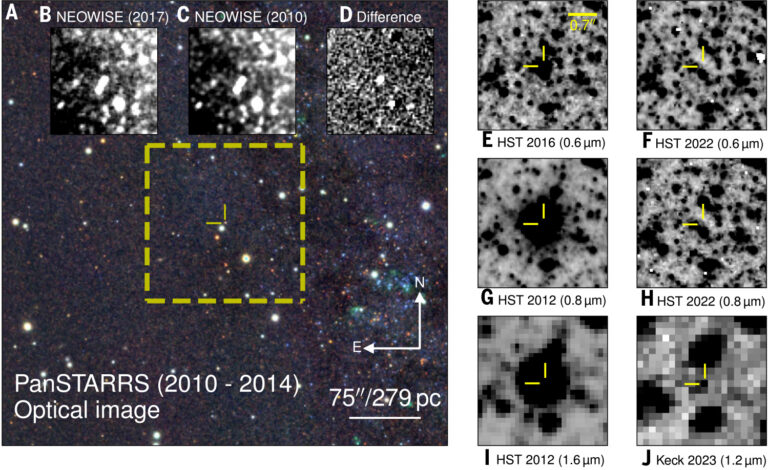

As the universe expands, wavelengths of light from distant objects stretch and become redder. The farther the object, the more stretching occurs. Early space telescopes like Hubble were built to detect shorter wavelengths of light. In that data, scientists saw interesting tiny objects they called little red dots (LRDs), but they couldn’t tell exactly what they were.

In 2022, the first deep images from the James Webb Space Telescope, which was designed to collect longer wavelengths of light, also revealed LRDs. The new data helped researchers ponder what these objects could be.

A new theory

Past theories explaining LRDs required complicated explanations involving black holes, accretion disks, and dust clouds. The new model, on the other hand, shows that one massive star can also produce the main features of LRDs: extreme brightness and a distinctive V-shaped spectrum with one bright hydrogen emission line.

So, the team created a model of a rare, metal-free, rapidly growing supermassive star about a million times the mass of the Sun, and showed that its features fit the observations of LRDs.

“Little red dots have been a point of contention since their discovery,” said Nandal. “But now, with new modeling, we know what’s lurking in the center of these massive objects, and it’s a single gigantic star in a wispy envelope. And importantly, these findings explain everything that Webb has been seeing.”

While stars across a wide range of masses align with both the spectral measurements for little red dots, only the most massive have the right luminosity. Nandal and his colleagues believe that if they can find additional little red dots that are less luminous and massive than those in the study, they will be able to uncover the truth about why and how this happens.

The new results are helping scientists come one step closer to understanding little red dots, providing direct evidence of the final, brilliant moments that occur just before a giant star collapses into a black hole.

“If our interpretation is right, we’re not just guessing that heavy black hole seeds must have existed. Instead, we’re watching some of them be born in real time,” said Nandal. “That gives us a much stronger handle on how the universe’s supermassive black holes and galaxies grew.”