For decades, astronomers have been aware of something weird lurking on old, 1950s-era photographic plates: starlike flashes of light (called “transients”) that appear from nowhere and vanish just as quickly. Since these plates were taken before the 1957 launch of Sputnik, the usual explanation of satellites or space junk was out. These mystery blips have generally been dismissed as plate defects.

But two new studies from researchers at Stockholm University and Vanderbilt University are pulling these anomalies out of the file cabinet. A study in Scientific Reports concludes that the appearance of these flashes statistically correlates with two of the Cold War’s strangest topics: nuclear bomb tests and, yes, reports of Unidentified Anomalous Phenomena (UAP).

Complementing this, a study in Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific (PASP) provides evidence that at least a third of these flashes are solar reflections, meaning something physical, flat, and highly reflective was in high Earth orbit, decades before we officially put anything there.

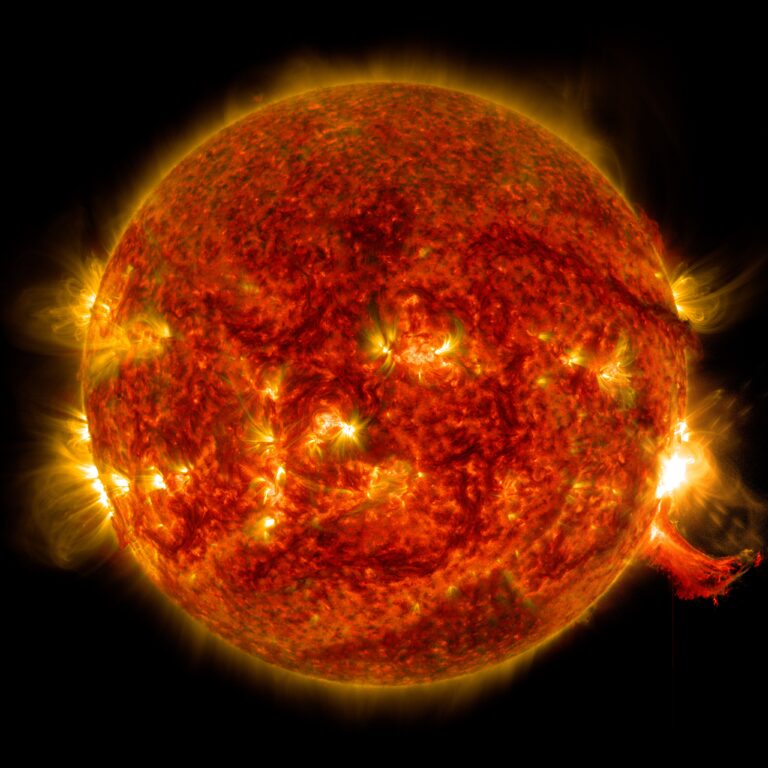

As Beatriz Villarroel, a researcher at the Nordic Institute for Theoretical Physics at Stockholm University and lead author of the PASP study, put it in a press release: “You don’t get that kind of solar reflections from round objects like asteroids or dust grains in space … only if something is very flat and very reflective and reflects the sunlight with a short flash.”

Things that go blink in the night

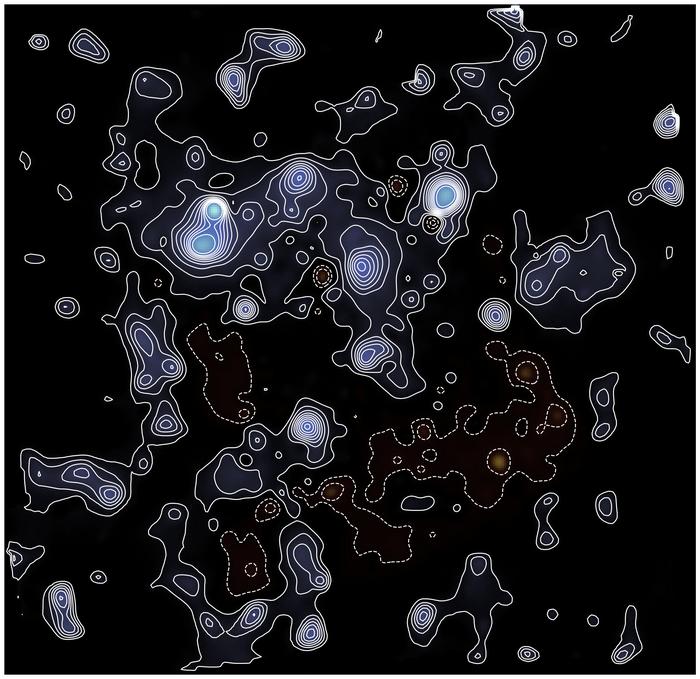

The study in Scientific Reports, led by Stephen Bruehl of Vanderbilt University, cross-referenced the flashes with other historical data. They used a large catalog of over 106,000 transient flashes, identified by the VASCO (Vanishing & Appearing Sources during a Century of Observations) project, from Palomar Observatory Sky Survey (POSS-I) photographic plates taken between 1949 and 1957. Then, they cross-referenced this database with two other datasets from the same period (1949-1957): a public list of all above-ground nuclear weapons tests and the comprehensive UFOCAT database of UAP sightings.

The correlations they found were statistically significant. A flash was 68 percent more likely to be recorded on the day after a nuclear test than on a random day. Furthermore, for every additional UAP reported on a given day, the number of flashes recorded in the sky increased by an average of 8.5 percent. The effects were also additive; on days that had both a recent nuke test and a UAP report, the number of flashes skyrocketed to more than double the norm.

The team argues this pattern makes “plate defects” an unlikely culprit — why would a chemical flaw on a glass plate care about a nuclear test or a UAP sighting? The day-after timing for nuke tests is also strange, seemingly ruling out direct bomb debris. This leaves the researchers with speculative, but data-backed, possibilities. One is an unknown, lingering atmospheric phenomenon. The other, the paper states, is “more speculative, drawing on a well-known strand of UAP lore suggesting that nuclear weapons may attract UAP.”

The team notes that while this link has been “claimed for decades based on anecdotal evidence, it has until now lacked any systematic supporting data.” They suggest their results “could be viewed as indicating that transients are artificial, reflective objects” in high orbit or in the atmosphere, adding to the “growing evidence supporting the interpretation of transients as real observations … rather than as emulsion defects.”

The secret hiding in the shadow

The study published in PASP moves from statistical correlation to a direct search for the objects themselves. For their methods, this team, led by Villarroel, hunted for two key pieces of evidence. The team’s findings hit the jackpot on both counts.

First, if these flashes are glints from a single, flat, spinning object (or a formation of objects), they might flash multiple times as they move, creating a line of flashes on a single long-exposure plate.

They found several promising alignments, including a 5-point alignment with a 3.9-sigma statistical significance (meaning the odds of it being a random chance alignment are roughly 0.8 percent) found on a plate from July 27, 1952. This is the same night as the famous “Washington Flap” UAP incident, where anomalous objects were tracked on radar over the White House and Washington, D.C.

Second, if the flashes are plate defects, they should be randomly scattered all over the plate. But if they are indeed solar reflections from objects in orbit, they physically cannot appear in the one place the sun doesn’t shine: the Earth’s umbra, or shadow. If you find flashes distributed evenly throughout the shadow, then they are likely defects. No flashes in the shadow? Now you’ve got something.

The team calculated the expected number of flashes that should have fallen in Earth’s shadow (if the flashes were indeed just defects) and compared it to what they actually found. The result: a third of the expected flashes were missing. They expected ~1,223 transients in the shadow, but only observed 349. This is a 22-sigma finding, a statistical grand slam that confirms the flashes must be avoiding the Sun’s shadow.

The paper concludes that at least one-third of the 106,000+ flashes aren’t defects at all. They are real, physical objects that are high enough to be in orbit and flat enough to be reflective.

So, what was it?

Together, these two studies paint a picture that is hard to ignore. The Scientific Reports study shows an unexplained behavioral link to nuke tests and UAPs. The PASP study provides the physical evidence that at least some of these things are real, high-orbit, reflective objects.

So what were they? The papers note the “non-terrestrial artifact” hypothesis, and the alignment on the same night as the 1952 D.C. UAP incident is a provocative coincidence. However, a more natural explanation is that nuclear tests create some unknown atmospheric phenomenon. This idea struggles to explain the flat, reflective nature of the objects or the one-day delay in their appearance.

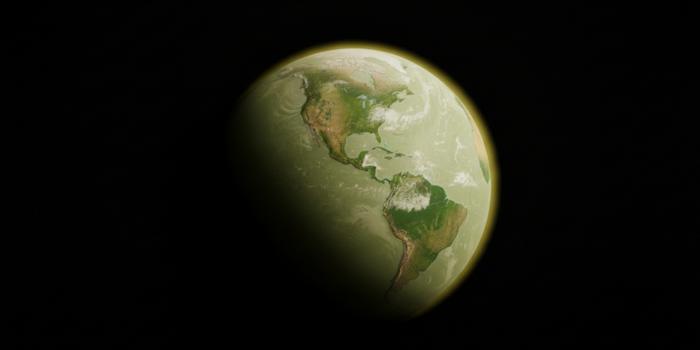

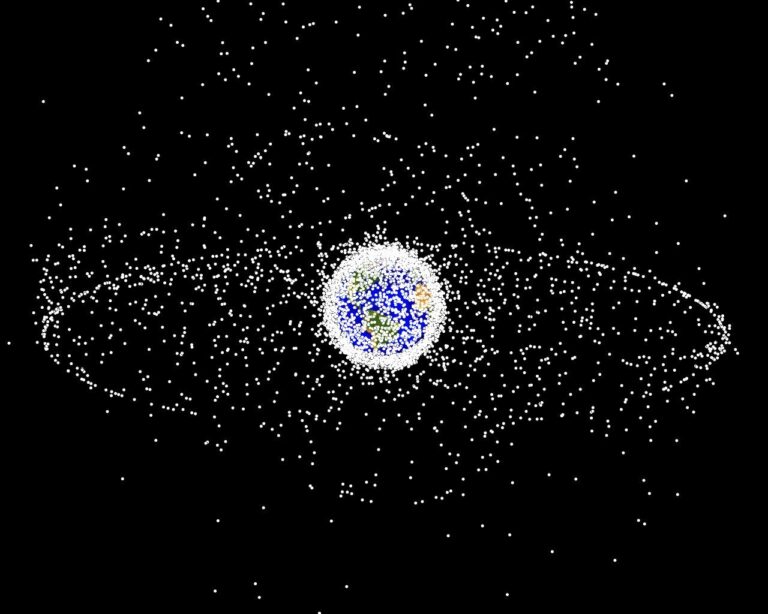

Ultimately, we’re left with one conclusion that seems unavoidable: The empty pre-Sputnik sky wasn’t so empty after all. The data seems clear: Something was up in high-Earth orbit, reflecting the sun. What it was, why it was, and why its appearance seems linked to humanity’s most sensitive activities is now, thanks to this new research, a very real scientific question.