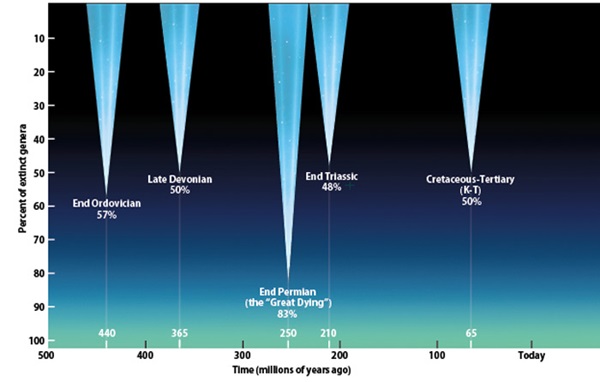

Key Takeaways:

- Earth's modern history features five major mass extinction events, with the Cretaceous-Tertiary (K-T) extinction being the most thoroughly studied. The K-T event, which led to the demise of approximately 50% of genera, is strongly associated with an asteroid impact 65 million years ago, supported by global iridium traces and the Chicxulub Crater, precipitating severe climate change.

- The Permian-Triassic (P-T) extinction stands as the most devastating in the history of complex life, resulting in the loss of about 83% of genera, including 95% of marine species; however, its precise causes remain largely enigmatic, although volcanism is a leading hypothesis.

- Causes for other significant extinction events vary, with speculations for the End Ordovician involving a gamma-ray burst, the Late Devonian possibly linked to an impact event, global cooling, or volcanism, and the End Triassic potentially resulting from volcanism, impact, or severely low oceanic oxygen levels.

- Attributing definitive causes to these mass extinctions is inherently difficult due to geological dating uncertainties ranging from hundreds of thousands to millions of years, the challenge of acquiring direct evidence, and the likelihood that each event stemmed from a complex combination of environmental and biological factors.

In the 1980s, a group of scientists, led by Nobel-prize-winning physicist Luis Alvarez, and his son, geologist Walter Alvarez, discovered fossilized traces of iridium, hundreds of times greater than normal. This iridium is spread throughout the world, and dates back to roughly 65 million years ago. Iridium is rare at Earth’s surface but is commonly found within asteroids and comets. The Alvarez hypothesis stated that an impact was the likely cause of the K-T extinction.

In 1990, Alan Hildebrand and colleagues studied a large crater just off the Yucatan peninsula in Mexico. Name Chicxulub Crater, it dates back to roughly 65 million years ago — corresponding to the K-T extinction event. Scientists now mostly believe a space rock impacted Earth roughly 65 million years ago, killing dinosaurs, and giving mammals a chance to thrive.

When a meteor impact carved out Meteor Crater in Arizona, it exposed a sequence of rocks that spans the P-T boundary. Sediments deposited precisely at the time of the P-T mass extinction, however, weren’t preserved in this part of the world. So the rocks exposed by the Meteor Crater impact event cannot be used to determine the cause of the P-T mass extinction. Scientists know the sea level rose, oxygen levels in oceans were low, and carbon dioxide levels were high — but what could have caused these effects?

All five mass extinctions likely resulted from a combination of environmental and biological reasons (a slow decrease in life over millions of years, global warming or cooling, sea levels rising), with one major event — environmental or extraterrestrial — tipping the balance. With the K-T extinction, an impact was the likely cause; with the late Ordovician, a group led by Adrian Melott of the University of Kansas, think a nearby gamma-ray burst could have send Earth into a nuclear winter (see “Do we live in a cosmic shooting gallery,” Astronomy November 2005); with the Permian, scientists think volcanism may have been the cause.

Was either of the other two — or both — from an impact event? Scientists have considered that the late Devonian may have been related to an impact event, global cooling, or volcanism. And the end-Triassic mass extinction? This extinction is the least understood of the big five. Scientists speculate maybe volcanism, an impact, or severely low levels of oxygen in the oceans led to roughly 50 percent of genera dying.

For any of these mass extinctions, all time measurements have an uncertainty of anywhere from a few hundred thousand years to a few million years. And unfortunately, direct evidence is difficult to come by.