The Biden Administration announced April 18 that it is committing to not conduct missile tests that launch from Earth to target and destroy satellites in a bid to establish an international norm against the practice.

In a speech at Vandenberg Space Force Base in California, Vice President Kamala Harris said the tests were a threat to U.S. national security and its growing commercial presence. “These tests, to be sure, are reckless, and they are irresponsible,” she said. “Whether a nation is spacefaring or not, we believe this will benefit everyone, just as space benefits everyone.”

She also called on nations to join the U.S. in banning such tests. “It is clear there is strong interest among our international partners to develop these norms,” said Harris.

The U.S. has not performed an anti-satellite (ASAT) test since 2008, so the move does not represent a significant practical shift. And the ban is limited to “destructive direct-ascent” tests, which would appear not to preclude destructive co-orbital tests — satellite to satellite attacks. It also would not cover nondestructive flight tests of direct-ascent ASAT missile systems. But it underscores concerns that additional tests, from any nation, could litter low Earth orbit with debris that threatens satellites and astronauts. And it follows the Artemis Accords as an example of U.S. attempts to assert a global leadership role in defining norms and regulations for the next era of space exploration.

“We must write the new rules of road,” said Harris. “And we will lead by example.”

Destructive tests

The U.S. is one of four nations that have performed ASAT tests; the others are China, India, and Russia. (The former Soviet Union was the first to demonstrate the capability.) But Russia’s most recent test Nov. 15, 2021, which targeted a satellite named Cosmos 1408, drew especially strong international condemnation.

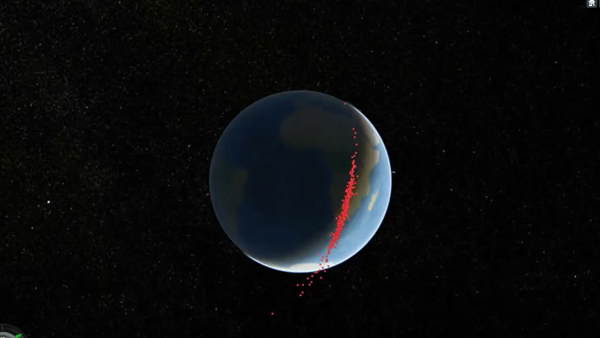

U.S. Space Command reported the destruction of Cosmos 1408 generated over 1,500 pieces of detectable orbital debris, and likely created hundreds of thousands of smaller, undetectable pieces. The test also briefly forced astronauts and cosmonauts on the International Space Station to take shelter in docked return capsules.

Cosmos 1408’s high altitude (300 miles, or 480 kilometers) and trajectory made it particularly likely to generate long-lasting debris, and to place it in the path of other spacecraft. Its orbit is less than 62 miles (100 km) above the ISS and the Chinese space station Tiangong, and a similar distance below many commercial satellites, including SpaceX’s Starlink constellation.

China’s 2007 test obliterated a satellite in an even higher orbit of about 530 miles (850 km), also creating a long-lived debris cloud. The U.S. test the following year and India’s test in 2019 targeted satellites in much lower altitudes, resulting in debris that reentered the Earth’s atmosphere more quickly.

The unilateral U.S. ban also comes nearly two months into Russia’s war against Ukraine, which Harris invoked as another example of Russia violating international norms. In response to the invasion, much of the world has cut off collaborations with Russia in space, including the European Space Agency’s joint ExoMars rover mission, which was scheduled to launch to the Red Planet later this year. ESA has said it is evaluating options to proceed with the mission without Russia.

Many space policy experts welcomed the U.S. ASAT ban, though cautioned it is a modest step. The moratorium “puts normative pressure on China, India, and Russia to follow suit and is something of an ‘easy win’ for the US,” tweeted Bleddyn Bowen, a space policy expert and lecturer at the University of Leicester. “But bear in mind that it is easy for states that have successfully tested weapons to ban testing for others that try to follow.”