For decades, the basic principles governing how the Internet works have remained pretty much unchanged. But with massive growth on the horizon — thanks to everything from AI to blockchain, and from the 5G rollout to the ubiquitous Internet of Things — the amount of data we produce could eventually outpace physical storage capacity.

The solution? Look to space. That’s the bet companies like Amazon, Facebook, OneWeb, and other Silicon Valley darlings are wagering on. Elon Musk, CEO of SpaceX, is planning to carpet low-earth orbit with thousands of satellites that will bring low-latency internet to all corners of the globe. Amazon is betting on a similar so-called mega-constellation worth billions, while Facebook created PointView Tech, a subsidiary to develop their secretive Athena broadband satellite, which was granted FCC approval to begin experimental trials.

If we want to build factories on the Moon or cities on Mars — or just keep up with current data growth trends — we’ll need a robust internet in space, these companies predict. And while networking operates very differently in zero gravity, the protocols it uses could actually be applied to terrestrial Wi-Fi as well. This symbiotic relationship may not only fix our issue with an overwhelming amount of data, it could reshape the internet itself.

Connectivity problems

If you’ve ever experienced an outage while streaming Netflix, it’s likely due to the internet protocol suite on your home network. Technically known as TCP/IP, it works (roughly) this way: one computer sends info via a router to a second router, then to your home computer. But none of this data is saved on the routers. If there’s a disruption in the connection, the information is lost, and you get buffering in the middle of Black Mirror.

In space, this model simply won’t fly. The extreme distances and orbital variances make the TCP/IP system untenable. So, NASA scientists invented a new protocol in 1998 called Delay/Disruption Tolerant Networking, also known as the Bundle Protocol.

“I think mobile apps that need to transfer data in ‘spotty’ connectivity would benefit from the Bundle Protocol’s patience,” says Vint Cerf, a co-inventor of both TCP/IP in the ’60s and DTN in the ’90s. Cerf is known as “the father of the internet” and he sees not only terrestrial applications for DTN, but also views the protocol as the backbone of manned and robotic missions beyond Earth.

DTN works by sending data in bursts. This avoids errors and lags by storing information until the connection returns. And it prioritizes what it sends by importance, helping further reduce latency.

Another improvement is that DTN has integrity checks and encryption built in, unlike TCP/IP, making it a more secure form of internet. Considering the vulnerabilities of IoT devices — which are notoriously easy to hack — DTN promises to make the web more protected.

There are a few ways DTN is already being used. For example, reindeer herders in remote areas of Swedish Lapland don’t have reliable internet access. So, a team of computer scientists tested a network using DTN protocols, allowing the Saami herders to check email and cached websites and even track their reindeer flocks. Similar experiments have taken place in Antarctica.

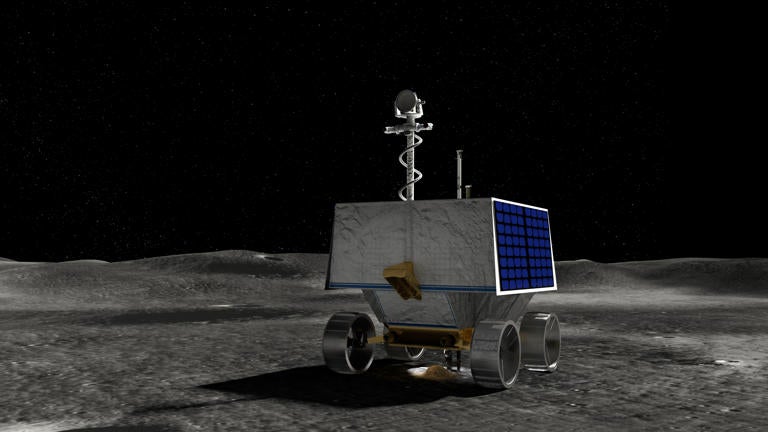

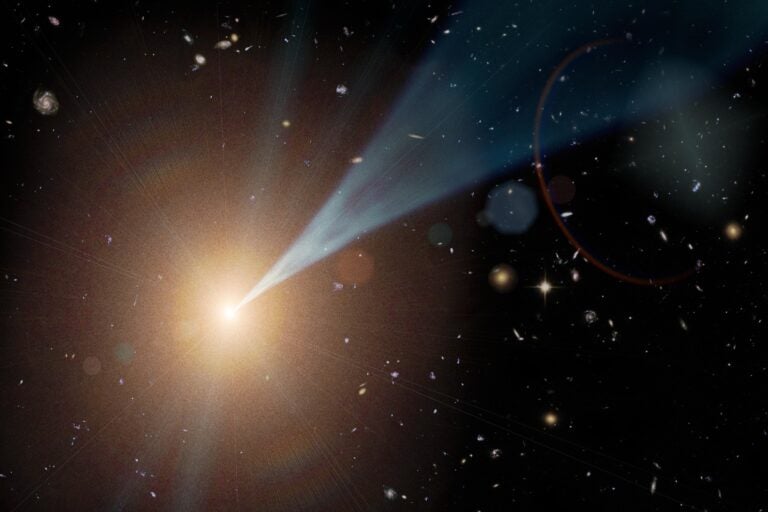

The tactic has also been used several times in outer space. DTN was enlisted to control the Spirit and Opportunity rovers, launch a bomb at a comet and is even regularly used aboard the International Space Station. Despite that success, it hasn’t seen broad rollout for commercial applications. At least, not yet.

Interplanetary broadband

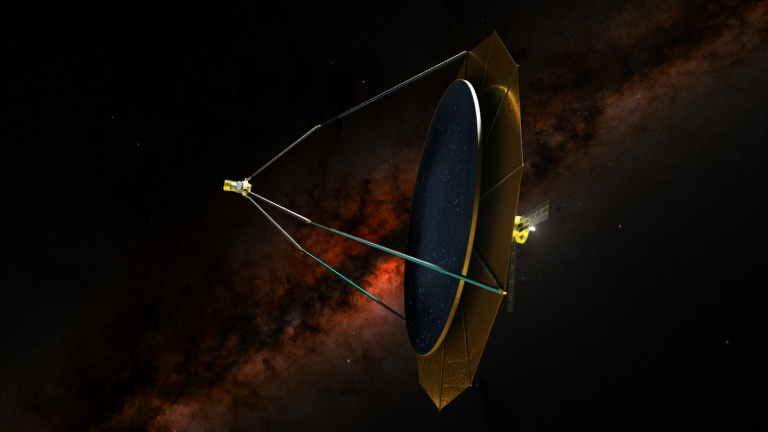

On May 24, SpaceX launched its first test of 60 Starlink satellites as part of the company’s proposed mega-constellation of 12,000 small satellites. It promises to deliver high-speed, low-cost internet to every point on the globe. But Musk also sees it as an essential step toward putting humans on Mars — another long-term goal for SpaceX.

“We could use the Starlink structure and leverage it to put an internet system on Mars,” Musk told reporters at a symposium in Seattle in June. “We are going to need high bandwidth communications between Earth and Mars and the Starlink system will provide this.”

But the first Starlink deployment wasn’t without problems. The satellites caused light pollution that drew outrage from the astronomy community. Some complained that doubling the objects in Earth orbit could make it harder to see and study the heavens, and even further contribute to space junk. According to Business Insider, SpaceX lost contact with three of the satellites. They will gradually deorbit — burn up in Earth’s atmosphere — over the next year. But some say these issues will likely be worked out as the projects scale.

“I am not sure it is possible to speak of right or wrong at this point,” Cerf says. “Something like 60 nodes have been launched for what I understand to be evaluation purposes — a prudent move before putting up thousands of satellites. There are concerns from astronomers that they will have an effect on Earth-based optical and radio astronomy. The low-Earth orbits reduce latency significantly, making satellite and terrestrial networking more similar.”

Bridging the gap between internet in space and on the ground may not just be a good business prospect — it may be necessary for the survival of companies like Amazon. The mega-corporation is best known for selling toothpaste and USB sticks from warehouses, but it also sells online data storage known as cloud computing. A lot of it. According to The Verge, Amazon controls as much as 40 percent of the programs running in the entire cloud. That’s more than Google, Microsoft and IBM combined.

But to keep up with the massive demand for data, Amazon may eventually have to move their servers off-planet. Bezos has said his plans for going to space will mitigate climate change and “save the Earth.” He’s not just talking server farms in low-earth orbit, but entire factories.

SpaceX and Amazon’s plans are still in the very early stages, however. Meanwhile, several smaller companies like Swarm and LyteLoop are racing to beat the major players, offering different variations on data storage in space. But history has shown that this nascent industry is incredibly expensive and most companies have failed before they’ve gotten off the launch pad.

Take Teledesic, for example. The ’90s startup received millions of dollars from Microsoft chairman Bill Gates and a Saudi prince, among others, to deploy 288 broadband satellites built by Boeing. But that didn’t stop the $9 billion project from flunking in 2002. Around nine other efforts from that period also promised to “darken the skies” with spacecraft, eventually fizzling out. Could the new race for satellite internet be déjà vu?

“The space industry is basing a lot of its growth on DTN and the rise of mega-constellations,” says Christopher Newman, Professor of Space Law and Policy at Northumbria University in the United Kingdom. “The question is essentially an economic one: can the market sustain both cable providers and internet-from-space … In essence, satellite providers are moving heavily into the telecommunications market and the mega-constellations are all predicated upon the market being able to support this alternative method of data delivery.”

In other words, interplanetary internet is still bound by the rules of capitalism: If Starlink or Project Kuiper can’t make money, the projects will likely phase out, like earlier, failed experiments. In the meantime, we could still be searching for signal.