The Moon would be a harsh place to call home. It has no weather and no liquid water. And with no atmosphere to hold conditions steady, lunar temperatures can oscillate from 224 degrees Fahrenheit (107 degrees Celsius) in the daytime to –228 degrees Fahrenheit (–144 C) at night. What’s more, the surface isn’t exactly ripe for agriculture. Buzz Aldrin once described lunar regolith, akin to soil, as “talcum powder-like dust.” And researchers who’ve studied lunar soil samples have described it as glassy, metallic, and loaded with minerals that have forms not commonly found on Earth.

That’s why it is so impressive that, for the first time, scientists have successfully grown plants using lunar soil gathered from previous missions to the Moon.

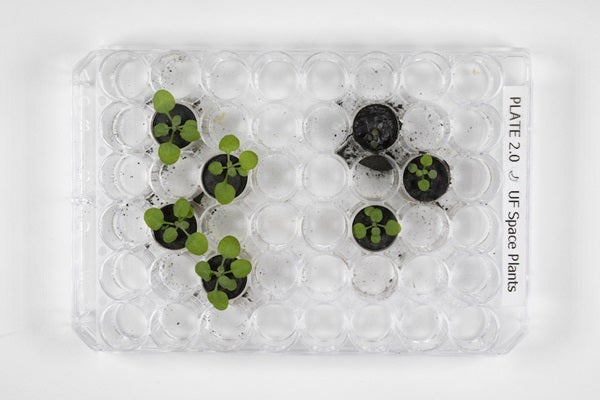

A study recently published in the journal Communications Biology documents the feat. According to study author Rob Ferl, a professor of horticultural sciences at the University of Florida, the experiment has been in the works for over a decade but researchers only carried it out last year. “Something like this takes tons of planning,” he says, because Moon soil is a finite resource and once you run out, it’s hard to come by. The team had only the equivalent of a few teaspoons to work with in a pot about the size of a thimble.

Lunar vs. terrestrial soil

In the years leading up to the experiment, researchers gathered soils from Earth that were as similar as possible to the makeup of lunar soil, says Ferl. In particular, they used soil sourced from around terrestrial craters, as well as a “lunar simulate soil” called JSC1A, an industrial mixture of chemicals meant to mimic the Moon’s soil conditions. He says getting things just right beforehand was imperative to optimizing growing conditions when the time came to plant in the real lunar soil.

The lack of a lunar atmosphere makes outdoor agriculture impossible, so researchers simulated a laboratory environment on the Moon instead. “Given conditions on the Moon, you can’t just throw seeds out on the surface and ask them to grow,” says Ferl.

He says lunar soil is different from what you might find on Earth because of the harsh solar wind and cosmic rays. Researchers found that the soil’s jagged edges and metallic minerals created suboptimal conditions for growing the Arabidopsis plant, a small flowering weed native to Europe and Asia. They chose this variety because unlike most other plants, its genes have already been mapped, making it easier to study the species’ gene expression as part of the experiment.

Stressed out

So, how did the plants fare? The team could tell both physically and biologically that the plants grown in the lunar soil struggled compared to control plants grown in terrestrial soil. “Plants grown in lunar soil tended to be smaller and they contained purplish pigments that were indications of stress. They also expressed genes typical of plants grown in marginal conditions like salty soils and soils with high metal content,” Ferl says.

But still, says Ferl, the plants grew — and that’s a big deal. Clive Neal, a researcher at Notre Dame who focuses on lunar exploration, agrees. He says that this was an excellent first experiment testing the “validity of using lunar regolith” to grow this novel set of Moon plants.

“The really intriguing thing is the results suggest mature regolith inhibits plant growth,” says Neal. The maturity of lunar soil is based on its exposure to solar winds and other inhospitable aspects the lunar surface. Researchers can pinpoint the soil’s maturity based on the size of granules as well as gases implanted in soil particles. But Neal says that there’s still a lot we don’t know. “We need more regolith returned from the Moon of varying degrees of maturity [to further study it],” he says.

Although this research is still in its infancy, Ferl is excited about where it might take researchers next. He says that this is about so much more than lunar soil. It’s about figuring out how plants can be a support system on other planets, just as they are on Earth. “What are the limits of our collective biology’s ability to live somewhere else in the solar system?” he asks.

And there’s also a more practical perspective: Ferl and his team want to figure out how to produce enough food so that humans can stay on the Moon and Mars for longer periods of time. And if plants could be a support system somewhere else in the solar system, then humans could provide their own food, rather than surviving on only what they’re able to bring along.

So, for Ferl and his team, this research is about more than growing lunar plants in a lab — it’s about surviving and thriving in a world outside of our own.