Last week’s passing of Ken Mattingly, aged 87, reduces the number of men still alive to tell tales of orbiting the Moon to eight. An intrepid lunar voyager and space shuttle commander, Mattingly was an obsessive workaholic whose colorful eccentricity belied a keen wit and razor-sharp mind. In the movie Apollo 13, his career took him to Hollywood’s silver screen.

Thomas Kenneth (“T. K.”) Mattingly II was born in Chicago on March 17, 1936, with aviation in his genes — his father worked for Eastern Airlines. “I built every model I could find,” he related, “ate every box of cereal that had a paper cut-out airplane on the back.” If he kept out of trouble, his father gave him employee passes to fly on a DC-3 airliner. Weekends were spent at airports, watching planes.

Mattingly graduated in aeronautical engineering from Auburn University in 1958 and joined the Navy, hoping to fly jets. But Lieutenant Commander Glenwood Clark felt guided missiles were naval aviation’s future and tried to talk the young ensign out of flight school. Mattingly stuck to his guns.

“You’re the dumbest ensign I’ve ever met,” Clark thundered. “Out!”

Mattingly won his wings in 1960, flew A-1H Skyraider attack aircraft and A-3B Skywarrior strategic bombers, then contemplated his future: a postgraduate degree or test pilot school. He picked the latter, graduating in 1966. That April, NASA tapped him for its fifth astronaut class.

He attained expertise on the Apollo Command and Service Module (CSM), but a 1969 letter from a friend in Vietnam gave him pause. How could he stay at NASA, Mattingly mused, when his Navy buddies were fighting a real war? He went to Chief Astronaut Alan Shepard, intent on returning to active duty. Shepard told him to stick around a while longer.

Ken Mattingly and the story of Apollo 13

In August 1969, Mattingly was named Command Module Pilot (CMP) on Apollo 13, America’s third Moon landing. Teamed with Jim Lovell and Fred Haise, he was the first “rookie” CMP, a job that required him to fly solo in lunar orbit. Earlier CMPs were veteran astronauts, skilled in systems knowledge and rendezvous.

Sadly, fate had other ideas.

Two weeks before their April 1970 launch, backup crewman Charlie Duke caught German measles, exposing Mattingly to the virus. Doctors feared its two-week incubation period might see Mattingly fall ill during the flight. The political backlash in flying a sick astronaut was unthinkable and delaying Apollo 13 until May carried a hefty $800,000 price-tag.

Instead, NASA switched Mattingly for his backup, Jack Swigert. The nature of the role of CMP made it a straightforward if imperfect solution. One astronaut compared it to dropping Glenn Miller into Tommy Dorsey’s band: both great musicians but with highly individualized styles. After months of training, Lovell, Haise and Mattingly knew the inflections of each other’s voices, an indispensable asset on a space mission.

Apollo 13 suffered an oxygen tank explosion halfway to the Moon, which cancelled the landing and crippled the spacecraft, with Lovell, Haise, and Swigert barely getting home alive. Even so, Lovell arranged codewords with Mission Control to check on Mattingly’s health. As Apollo 13 headed home, he radioed an odd question.

“Are the flowers blooming in Houston?”

“No,” replied Capsule Comunicator (CapCom) Vance Brand. “Still must be winter.”

“Suspicions confirmed.”

The blooms of measles never did strike Ken Mattingly. And he played a key role in the crew’s safe return, helping mission controllers and engineers to devise a procedure to cold start the Command Module with the systems that were still functioning.

Offered options to fly as CMP with John Young and Charlie Duke on Apollo 16 or walk on the Moon on Apollo 18, Mattingly knew that later missions risked cancellation. He took Apollo 16, “a bird in the hand” and a propitious choice as Apollo 18 indeed met its demise at the sharp end of the budget axe.

More troubleshooting on Apollo 16

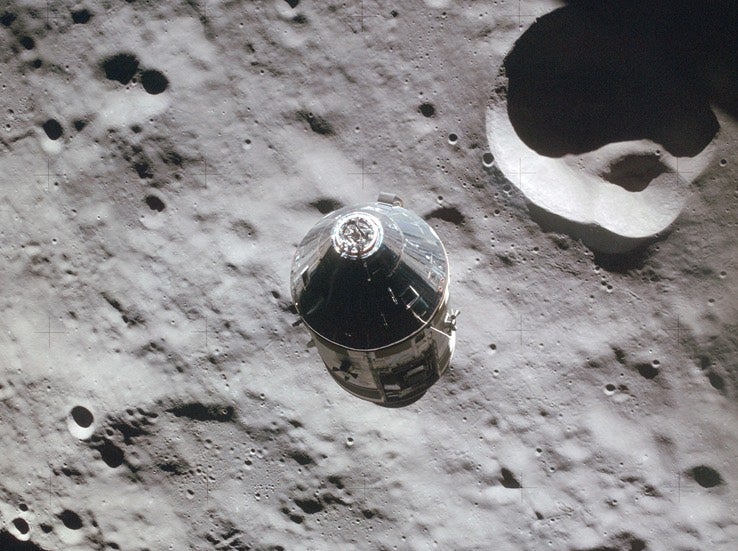

Launched on April 16, 1972, Mattingly savored weightlessness but regretted insufficient time to look at the Earth. Orbiting the Moon solo was exhilarating and he used mapping cameras, laser altimeters, mass spectrometers, and his own eyes to scrutinize an intractable grey landscape, as the strains of Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique and Holst’s The Planets boomed from a tape player.

Homebound from the Moon, with the Earth a sliver-like crescent, 200,000 miles (320,000 kilometers) away, Mattingly made an 84-minute spacewalk to retrieve film magazines from cameras mounted inside the Service Module. He also performed an experiment in which he exposed microbial specimens to space for 10 minutes, and brought them back onboard for post-flight analysis.

Mattingly also helped save Young and Duke’s Moon landing. Having undocked the CSM from their Lunar Module (LM), he prepared to fire the engine to circularize his ship’s orbit. But during a scheduled pre-burn test of the gimbals that steered the engine, one of the backup gimbals began oscillating, swiveling the engine from side to side and causing the craft to shudder like a train on a rickety track. If the CSM’s engine was faulty, a landing was off the cards. The crew were forced to wait as Mission Control deliberated whether to move forward with the landing.

Few engineers knew that the control signals to the CSM’s engine for both the primary and backup gimbals ran through a single cable. What’s more, the cable had previously been found to be too short, and was prone to coming unplugged when the engine swiveled all the way over. Mattingly learned this before launch, and thought the cables had been replaced. He decided not to mention the cabling as he troubleshooted the gimbal oscillations with Mission Control, but the fear of a double control failure played on his mind. After a nearly six-hour delay, Mission Control approved the landing to go ahead.

After the flight, chatting to Apollo Program Manager Jim McDivitt, he expressed astonishment that Young and Duke had been allowed to land.

“We didn’t know they went through the same cable,” McDivitt laughed. “You’re the only one who did. If we’d known, we wouldn’t have let you land!”

The Shuttle Columbia years

Ten years later, in June 1982, Mattingly commanded the Space Shuttle Columbia’s fourth orbital mission, STS-4. Flying with Pilot Hank Hartsfield, the duo tested the reusable spaceplane, including its Canadian robot arm and space suit. They also did several secret Air Force experiments, their names disguised in the checklist under cryptic code-words.

Near the flight’s end, after packing away the secret experiments, Mission Control told them an Air Force officer wanted to speak to them on a secure link. He told Mattingly to “do Tab November”.

The astronauts exchanged glances. What was Tab November? Military secrecy precluded them from openly asking over the airwaves. Their only option was to unpack the experiments, find the checklist and identify the code-word. After much searching, they found the glossary entry for Tab November: “Pack everything away and secure it.”

This cloak-and-dagger secrecy became more acute on Mattingly’s second shuttle mission, STS-51C in January 1985, whose crew launched a Pentagon spy satellite. The astronauts had secret meeting rooms, a secret safe for their documents, and a secret phone with an unlisted number. In all their time training together, the phone rang once. It was a sales call.

Mattingly even had to disguise his training destinations, filing flight plans to certain places, then renting cars to reach off-the-beaten-track military sites. On one occasion, their secretary booked them secretly into a motel, but upon arrival the crew was astonished to spot an enormous message on the marquee: Welcome, STS-51C Astronauts.

When STS-51C ended, so did Mattingly’s astronaut career, with a return to active duty in the Naval Space and Warfare Systems Command. At the Pentagon, he met his commanding officer, Vice Admiral Glenwood Clark, the same figure who sought to dissuade him from flight school a quarter-century before.

“Admiral,” said Mattingly. “Do you remember me?”

Clark looked him straight in the eye.

“I sure do. You were the dumbest ensign I ever met!” The two men laughed.

Aside from flying in space, Mattingly supervised the training of the shuttle’s first astronauts. His fanatical attention to detail made him a quasi-comical figure to his fellow astronauts, remembered by Dave Leestma for his action items in green ink and by James van Hoften for his to-do lists, which never got shorter. Jim Lovell praised him as “conscientious” and George “Pinky” Nelson joked that Mattingly “didn’t just see the forest, he saw every tree.”

When Mattingly landed Columbia on July 4, 1982, the only U.S. space mission to end on Independence Day, he was welcomed home by President Ronald Reagan, who lauded him as an “inspiration”. But Mattingly had a different message for his rapt young audience. “Where we’re going to go in the future,” he said, “is something that depends on you.”