One of the biggest comet findings coming out of the amazing images and data taken by the University of Maryland-led EPOXI mission as it zipped past Comet 103P/Hartley last week is that dry ice is the ‘jet’ fuel for this comet and perhaps many others.

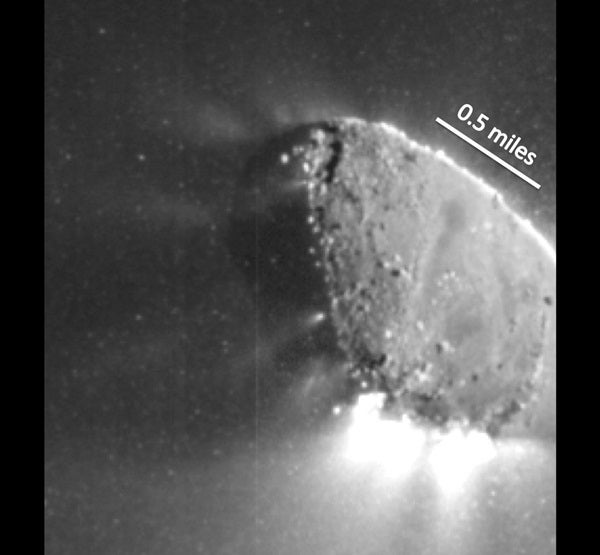

Images from the flyby show spectacular jets of gas and particles bursting from many distinct spots on the surface of the comet. This is the first time images of a comet have been sharp enough to allow scientists to link jets of dust and gas with specific surface features. Analysis of the spectral signatures of the materials coming from the jets shows primarily carbon dioxide (CO2) gas and particles of dust and ice.

“Previously it was thought that water vapor from water ice was the propulsive force behind jets of material coming off of the body, or nucleus, of comet,” said University of Maryland astronomy professor Jessica Sunshine, who is deputy principal investigator for the EPOXI mission. “We now have unambiguous evidence that solar heating of subsurface frozen carbon dioxide (dry ice) directly to a gas, a process known as sublimation, is powering the many jets of material coming from the comet. This is a finding that only could have been made by traveling to a comet, because ground-based telescopes can’t detect CO2 and current space telescopes aren’t tuned to look for this gas.”

Sunshine and other members of the EPOXI science team are meeting all this week at the University of Maryland to analyze the very large amount of data from the closest approach, and new data continues to come down at a rate of some 2,000 images each day.

The Deep Impact spacecraft that flew past Comet Hartley has three instruments — two telescopes with digital color cameras and an infrared spectrometer. The spectrometer measures the absorption, emission and reflection of light (spectroscopic signature) that is unique to each molecular compound. This allows Maryland scientists to determine the composition of the material in the jets and on the comet’s surface. They have found that water and carbon dioxide dominate the infrared spectrum of Comet Hartley’s environment and that organics, including methanol, are present at lower levels.

This is no surprise to scientists. But what is surprising is that there is a lot more carbon dioxide escaping this comet than expected.

“The distribution of carbon dioxide and dust around the nucleus is much different than the water distribution, and that tells us that the carbon dioxide rather than water takes dust grains with it into the coma as it leaves the nucleus,” said assistant research scientist Lori Feaga. “The dry ice that is producing the CO2 jets on this comet has probably been frozen inside it since the formation of the solar system.”

From Deep Impact to Hartley 2

According to University of Maryland research zcientist Tony Farnham, findings from the team’s 2005 Deep Impact mission to Comet Tempel 1, though less conclusive, nonetheless indicate that the 103P/Hartley findings that super-volatiles (CO2) and not water drive the activity probably are a common characteristic of comets. “Tempel 1 was most active before perihelion when its southern hemisphere, the hemisphere that appeared to be enhanced in CO2, was exposed to sunlight,” said Farnham, a member of both the Deep Impact and EPOXI science teams. “Unlike our Hartley encounter, during the flyby with Tempel 1, we were unable to directly trace the CO2 to the surface because the pole was in darkness during encounter.”

The Maryland scientists devised the plan to reuse the Deep Impact spacecraft and travel to a second comet in order to learn more about the diversity of comets and the processes that govern them. This became the EPOXI mission on which the spacecraft has flown to Comet 103P/Hartley.

The spacecraft’s images show that Hartley has an elongated nucleus, 1.2 miles (2 kilometers) in length and 0.2 mile (0.4 km) wide at the narrow neck. Hartley is only the fifth cometary nucleus ever seen and exhibits similarities and differences to the bodies or nuclei of other comets.

Mission principal investigator and science team leader Michael A’Hearn, a University of Maryland professor of astronomy, said the mission has provided, and continues to provide, a tremendous wealth of data about Comet 103P/Hartley, and the team expects to announce more science findings in the coming weeks.

One of the biggest comet findings coming out of the amazing images and data taken by the University of Maryland-led EPOXI mission as it zipped past Comet 103P/Hartley last week is that dry ice is the ‘jet’ fuel for this comet and perhaps many others.

Images from the flyby show spectacular jets of gas and particles bursting from many distinct spots on the surface of the comet. This is the first time images of a comet have been sharp enough to allow scientists to link jets of dust and gas with specific surface features. Analysis of the spectral signatures of the materials coming from the jets shows primarily carbon dioxide (CO2) gas and particles of dust and ice.

“Previously it was thought that water vapor from water ice was the propulsive force behind jets of material coming off of the body, or nucleus, of comet,” said University of Maryland astronomy professor Jessica Sunshine, who is deputy principal investigator for the EPOXI mission. “We now have unambiguous evidence that solar heating of subsurface frozen carbon dioxide (dry ice) directly to a gas, a process known as sublimation, is powering the many jets of material coming from the comet. This is a finding that only could have been made by traveling to a comet, because ground-based telescopes can’t detect CO2 and current space telescopes aren’t tuned to look for this gas.”

Sunshine and other members of the EPOXI science team are meeting all this week at the University of Maryland to analyze the very large amount of data from the closest approach, and new data continues to come down at a rate of some 2,000 images each day.

The Deep Impact spacecraft that flew past Comet Hartley has three instruments — two telescopes with digital color cameras and an infrared spectrometer. The spectrometer measures the absorption, emission and reflection of light (spectroscopic signature) that is unique to each molecular compound. This allows Maryland scientists to determine the composition of the material in the jets and on the comet’s surface. They have found that water and carbon dioxide dominate the infrared spectrum of Comet Hartley’s environment and that organics, including methanol, are present at lower levels.

This is no surprise to scientists. But what is surprising is that there is a lot more carbon dioxide escaping this comet than expected.

“The distribution of carbon dioxide and dust around the nucleus is much different than the water distribution, and that tells us that the carbon dioxide rather than water takes dust grains with it into the coma as it leaves the nucleus,” said assistant research scientist Lori Feaga. “The dry ice that is producing the CO2 jets on this comet has probably been frozen inside it since the formation of the solar system.”

From Deep Impact to Hartley 2

According to University of Maryland research zcientist Tony Farnham, findings from the team’s 2005 Deep Impact mission to Comet Tempel 1, though less conclusive, nonetheless indicate that the 103P/Hartley findings that super-volatiles (CO2) and not water drive the activity probably are a common characteristic of comets. “Tempel 1 was most active before perihelion when its southern hemisphere, the hemisphere that appeared to be enhanced in CO2, was exposed to sunlight,” said Farnham, a member of both the Deep Impact and EPOXI science teams. “Unlike our Hartley encounter, during the flyby with Tempel 1, we were unable to directly trace the CO2 to the surface because the pole was in darkness during encounter.”

The Maryland scientists devised the plan to reuse the Deep Impact spacecraft and travel to a second comet in order to learn more about the diversity of comets and the processes that govern them. This became the EPOXI mission on which the spacecraft has flown to Comet 103P/Hartley.

The spacecraft’s images show that Hartley has an elongated nucleus, 1.2 miles (2 kilometers) in length and 0.2 mile (0.4 km) wide at the narrow neck. Hartley is only the fifth cometary nucleus ever seen and exhibits similarities and differences to the bodies or nuclei of other comets.

Mission principal investigator and science team leader Michael A’Hearn, a University of Maryland professor of astronomy, said the mission has provided, and continues to provide, a tremendous wealth of data about Comet 103P/Hartley, and the team expects to announce more science findings in the coming weeks.