Four months of exploring martian terrain with robotic geologists Spirit and Opportunity has given NASA scientists an unprecedented glimpse of the Red Planet. Steven Squyres, principal Mars rover investigator, and his science team came to Montreal, Canada, last week to share their latest findings at a special Mars session of the 2004 Joint Assembly of the American and Canadian Geophysical Unions.

One mystery that has stumped scientists is the origin of the famous “blueberry” spherules scattered throughout Opportunity’s landing site at Eagle Crater. These grains, which measure between an eighth and a quarter of an inch (3 to 6 millimeters), increase in abundance toward the rock outcrops on the sides of the crater and are randomly embedded within the layered rocks. Scientists believe the blueberries simply weather out of the rock and fall to the floor of the crater. They are the most likely candidates for the strong spectral signature of hematite seen in orbital and rover images.

After climbing out of the crater into the surrounding plains, Opportunity found sand ripples everywhere marked by high hematite readings, however, the microscopic imager revealed much smaller grains as the culprit. Scientists soon realized that sand ripples at Spirit’s site harbor similar minute grains. The tiny globes in Gusev, however, are made of basaltic or volcanic material.

“This must imply some local process that breaks things down to itty-bitty grains, and it just happens to be that at Meridiani they’re made of hematite and at Gusev they’re made of basalt,” says Jeff Johnson, member of the rover science team and the U.S. Geological Survey in Flagstaff, Arizona. Scientists believe that the hematite blueberries at Meridiani may have formed within watery conditions, and they plan to conduct detailed mineralogical investigations of these spheroids over the coming months.

Opportunity now is perched on the rim of a stadium-size crater named Endurance, cautiously making a counter-clockwise panoramic tour along its rim. Surveys of the steep sides of the crater reveal overhanging cliffs of exposed rocks with distinct light- and dark-colored layering. Results from the rover’s infrared remote-sensing instrument (Mini-TES) suggest these layers may be sandstones deposited by wind or water. Tempting as these formations are, they sit on a relatively steep slope of the crater and may represent a target too hazardous for Opportunity to approach. “We need to find a place where we can dip our toes into the crater and sample the rocks safely,” Squyres says.

While circumnavigating Endurance, Opportunity examined a brick-size rock believed to be ejecta from the impact that formed the crater. Rover data revealed a sulfur-rich composition, with fine layering and spherical concretions — all strong indications that the rock formed under wet conditions.

Post Endurance, Opportunity will drive over 300 feet (100 meters) to the south and take a look at its own heat shield, which struck the planet at over 185 miles (300 kilometers) an hour when it impacted. The team hopes the heat shield’s deep, fresh crater will expose subsurface material beyond the rover’s own ability to create a trench.

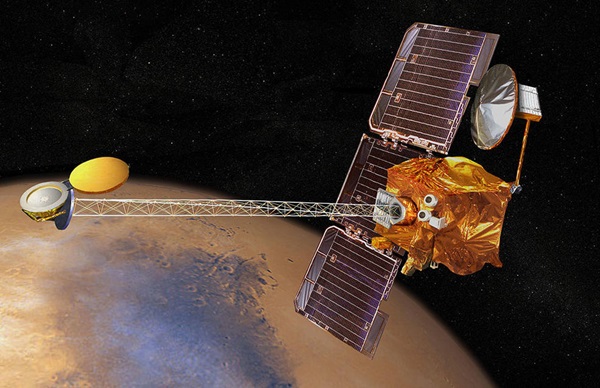

With geologists now resigned to the possibility that hard evidence for past water may lie buried or masked from view at the Gusev landing site, the rover is making haste toward a cluster of hills on the horizon. Images from Mars Global Surveyor show that the material Spirit landed on comes to a distinct edge exactly at the foot of the Columbia Hills, pointing to the possibility, according to Grant, that the hills may be composed of different material. The rover team hopes these formations may hold clues to the presence of water in Gusev.

“By crossing over that edge, we hope to get off the material that we landed on and access these new materials, which look to be older and may be the stuff that we’ve been looking for since we landed,” explains Grant. “We might see the material that may have been flushed into the crater from Ma’adim Vallis,” a prominent channel-like feature that breeches the southern rim of Gusev Crater.

Spirit keeps setting distance records — over 420 feet (130 meters) on May 20 — on its relentless drive toward the Columbia Hills, which are now less than half a mile away. “Spirit is making breathtaking progress,” says Squyres. “This kind of pace bodes well for having lots of rover capability left when we get to the hills.” Although not scheduled to arrive at the hills until mid-June, Spirit’s close-up images already are revealing exposed bedrock, giant boulders, and landslide scars across the beckoning hillsides.

“Things are going to get real interesting soon,” Squyres says.