Astronomy uses a lot of acronyms — some clever, some silly. But one astronomical instrument that only sounds like an acronym is Spitzer, a space telescope that’s spent the past 16 years scouring the heavens for infrared light.

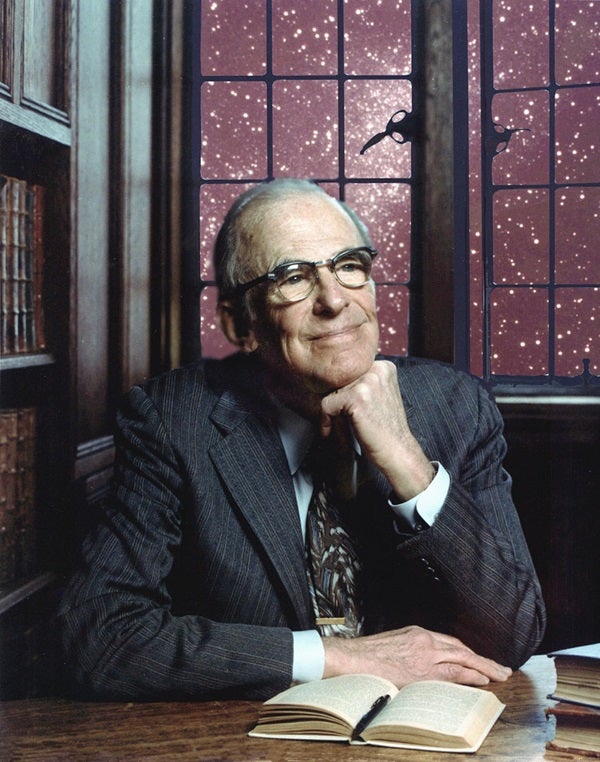

The Spitzer Space Telescope’s intriguing name pays homage to an astrophysicist named Lyman Strong Spitzer, Jr. who is often considered one of the most renowned scientists of the 20th century. In addition to a slew of valuable contributions to astrophysics, Spitzer is recognized as the first person to propose launching a large telescope into space to help us get a better view of the cosmos.

Who was Lyman Spitzer?

A relative of inventor Eli Whitney, Lyman Strong Spitzer, Jr. was born in 1914 in Toledo, Ohio. Always eager to learn, Spitzer spent much of his early adult life hopping between some of the United States’ most prestigious universities.

According to a detailed article from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), Spitzer earned a bachelor’s degree in physics from Cambridge University in 1935, a master’s degree from Princeton in 1937, and a Ph.D. in astrophysics from Princeton in 1938. He then spent a year as a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard before earning a faculty position at Yale in 1939. At this point, he was only in his mid 20s.

After the U.S. joined World War II, Spitzer was recruited by the U.S. Navy’s Division of War Research at Columbia University. There, he helped carry out valuable underwater sound research which ultimately led to the development of sonar technology. Following the war, Spitzer ventured back to Yale to briefly continue his tenure as a professor.

Proposing a space-based observatory

In 1946, after becoming part of a think-tank set up by the U.S. military, Spitzer published a report titled “Astronomical Advantages of an Extra-Terrestrial Observatory,” which proposed the U.S. government should launch a large telescope into space. This way, Spitzer argued, astronomers could bypass the obscuring effects of Earth’s turbulent atmosphere, allowing for views of the cosmos with unprecedented resolution. Additionally, Spitzer’s report notes that a telescope in space would allow for detailed observations in infrared and ultraviolet light, wavelengths largely blocked by Earth’s atmosphere. This, Spitzer hoped, would open the door to observations of the universe that were never before possible.

A year later, at just 33, Spitzer was appointed chairman of Princeton’s Department of Astrophysical Sciences, as well as the director of Princeton’s Observatory. Working with Martin Schwarzschild (son of German astrophysicist Karl Schwarzschild, who found the first exact solution to Einstein’s field equations of general relativity), Spitzer helped turn Princeton’s astrophysics department into a world-class research facility.

At Princeton, Spitzer pursued his interest in star formation and carried out foundational research on the interstellar medium — the dusty material that populates the space between stars and condenses to form new ones.

Among Spitzer’s many other astronomical contributions, the JPL article describes how he is often credited with being one of the first people to suggest that the bright stars shining in spiral galaxies burst to life relatively recently, forged from gas and dust from the interstellar medium. This realization led Spitzer to recognize that star formation is an ongoing process that still occurs throughout the cosmos today.

As Spitzer’s illustrious career continued, in 1951, he helped the U.S. government on a secret fusion research project codenamed Project Matterhorn — a name which Spitzer, an avid mountaineer, suggested. The lab is better known today as the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory.

Spitzer had a great interest in plasma physics because he wanted to understand the inner workings of stars. But he also deeply cared about creating energy from fusion for peaceful applications. Key to his attempts for controlled nuclear fusion was the funding he obtained to create the “stellarator,” a device he envisioned would use magnetic fields to contain hot, charged plasma gas. The device never quite lived up to expectations, though.

A long road to Hubble

By the early 1960s, Spitzer revived his push for a large, space-based telescope, which seemed tantalizingly possible following the birth of NASA in 1958. In 1962 (following a two-year stint as president of the American Astronomical Society), Spitzer was tasked with leading the development and design of an ultraviolet observatory that would orbit Earth to scan the cosmos without interference from our planet’s atmosphere.

After years of hard work, NASA launched the Orbiting Astronomical Observatory-3 (OAO-3; also known as Copernicus) on August 21, 1972. It came equipped with a 31.5-inch ultraviolet telescope built by Princeton University.

OAO-3 was actually the fourth space telescope NASA attempted to place into Earth orbit. The first (OAO-1) launched in 1966 and failed after just three days. The second (OAO-2) launched in 1968 and was moderately successful, lasting until 1973. The third (OAO-B) launched in 1970 but didn’t to make it to orbit. And the last, Spitzer’s OAO-3, would prove to be the most successful of these early telescopes, and it continued observing the cosmos until 1982.

Riding on the success of OAO-3 mission, Spitzer continued to make a compelling case to NASA and Congress for sending a larger, more advanced space telescope into space. By 1975, Spitzer has successfully won enough support from scientists that NASA and the European Space Agency began developing what would become the Hubble Space Telescope.

Finally — some 44 years after Spitzer first proposed sending a large telescope above the blurring haze of Earth’s atmosphere — Space Shuttle Discovery successfully deployed Hubble into Earth orbit on April 24, 1990. And, despite a few major hurdles early in its life, the iconic telescope has been steadily pumping out fascinating science and images for the past 30 years.

Honoring Lyman Spitzer

At the age of 82, Lyman Strong Spitzer, Jr. died unexpectedly on March 31, 1997, shortly after completing a regular day of work at his beloved Princeton University — the place where he spent more than half of his life.

Fast forward a few years and NASA launches the Space Infrared Telescope Facility (SIRTF) on August 25, 2003. Because SIRTF was put into an Earth-trailing orbit around the Sun, it was able to observe space free of interfering infrared radiation from our planet. This made SIRTF the fourth and final member of NASA’s Great Observatories program, which included Hubble, SIRTF, the Compton Gamma Ray Observatory, and the Chandra X-ray Observatory.

But, partly because SIRTF is not the catchiest acronym, NASA sponsored a contest to rename the nearly 1-meter, dust-penetrating telescope. After sorting through more than 7,000 essays proposing alternative names, NASA ultimately went with the Spitzer Space Telescope, honoring the visionary scientist who helped pave the way for what would become a wide-ranging fleet of large space telescopes.