Astronomy reached out to two respected scholars of the Space Age to gain perspectives on America’s two crewed programs for lunar exploration: the Apollo missions of the 1960s and 1970s, and the Artemis missions of the 21st century.

Here’s what they had to say.

Comparing Artemis with Apollo is only natural. The spacecraft look similar, they are both lunar exploration programs, and even the names suggest a familial bond. But when it comes to the larger geopolitical context —and the question of whether or not we are in the midst of a new Space Race — the similarities between the programs dissolve.

President Kennedy proposed Project Apollo as a political response to the threat of Soviet influence on the world order. He saw spaceflight as an essential form of soft power in the United States’ contest for geopolitical alignment and international influence. The Artemis program is not primarily aimed at international audiences and global influence. The United States is not sending humans to the lunar South Pole to win the hearts and minds of the world, and convince countries to pursue liberal democracy as opposed to socialist democracy or communism. Spaceflight does not serve the same role in international politics that it did in the 1960s. Today, we look to space diplomacy to create stronger bonds between nations, advance science, and prevent military conflict, among other objectives. In the 1960s, however, it was part of a larger ideological contest about how societies should be organized.

The first lunar landing brought people together. It drew the largest audience in history. People on every continent stopped what they were doing — no matter what time of day or night — to watch those first steps live, together. Across the world, people expressed a sense of global citizenship and unity. Will Artemis inspire the same sentiment? Will it close the divisions we observe today? It is too early to tell. But, like Apollo, it will expand human experience. Humans will experience something that has never been experienced before. For Apollo, it was setting foot on another celestial object. For Artemis, it will be living and working on another world. By extending the bounds of our experience, spaceflight will again broaden what it means to be human, a process that is likely as meaningful today as it was in 1969.

— Teasel Muir-Harmony

Project Apollo curator, National Air and Space Museum

About the only similarity between Apollo and Artemis is the destination — the surface of Earth’s Moon. Apollo was a unilateral effort driven by Cold War politics and was a head-to-head race to see whether the United States or the Soviet Union would get to the Moon first. Science and exploration were decidedly secondary objectives; the goal was simply safely getting to the Moon and back to Earth. Apollo was never planned as the beginning of a sustained program of solar system exploration. Once the United States won the race to the Moon, there was enough inertia (and hardware) to support a few more missions, but no approved plan for what would follow. So the United States after 1972 simply stopped human exploration.

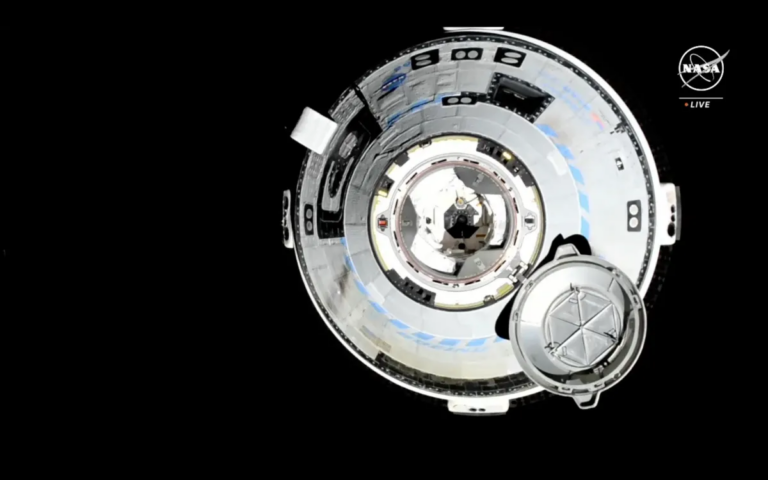

Artemis, according to the December 2017 policy directive that began it, is intended to be the first step in “an innovative and sustainable program of exploration with commercial and international partners to enable human expansion across the solar system and to bring back to Earth new knowledge and opportunities. Beginning with missions beyond low-Earth orbit, the United States will lead the return of humans to the Moon for long-term exploration and utilization, followed by human missions to Mars and other destinations.” Competition with other countries, especially China, is a secondary objective compared to such a sustained exploration effort. The Artemis 1 mission is the first step in the path toward this bold objective. Time will tell whether the United States has the political will to lead such a long-term effort.

— John M. Logsdon,

Professor Emeritus of Political Science and International Affairs, Space Policy Institute at the Elliott School of International Affairs, George Washington University