Overhead, some 5,000 satellites orbit in what’s called low Earth orbit (LEO). Most of these satellites are focused on scientific pursuits, but others are crucial to our global communication networks. The permanently staffed International Space Station (ISS) also calls LEO home.

LEO ranges in altitude from 100 miles (160 kilometers) up to 1,200 miles (2,000 km) above Earth’s surface. Objects in LEO aren’t slothfully circling Earth, either, they travel at around 15,700 mph (25,000 km/h). But satellites aren’t the only objects that inhabit this region.

The U.S. Department of Defense’s global Space Surveillance Network (SSN) is tracking over 27,000 pieces of space junk in LEO. Much more orbital debris that is too small for tracking but still large enough to pose a threat to missions also resides in LEO.

Both space junk and spacecraft in LEO are on the rise. And that increases the probability of a collision. Thankfully, Earth’s atmosphere stretches up into LEO, creating drag on debris that eventually reins in its orbit until it burns up in the lower atmosphere.

However, a recent study published Sept. 23 in Geophysical Research Letters shows that increased levels of carbon dioxide will reduce the density of Earth’s upper atmosphere. And that will ultimately increase how long space debris takes to burn up.

The atmospheric cake

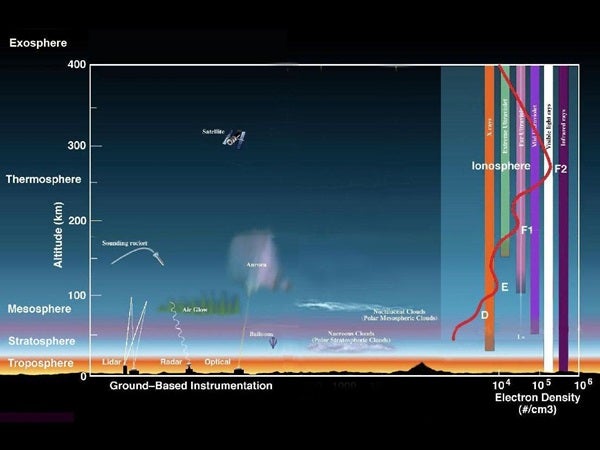

Earth’s atmosphere is kind of like a layered cake. At the very bottom is the troposphere, which holds all the air plants and animals need to survive. Next are the stratosphere and mesosphere, respectively. Then comes the thermosphere. This is where the ISS orbits, at an average altitude of about 250 miles (400 km). And finally, the icing on this atmospheric cake: the exosphere.

As CO2 increases, the troposphere warms. But the opposite is true in the stratosphere, mesosphere, and thermosphere. These layers cool down with increasing CO2, causing the atmospheric layers to contract.

In the short-term, lower atmospheric density at high altitudes isn’t a huge concern. But in the long-term, the effect can significantly increase the lifetime of space debris.

Diminishing drag

To calculate the impact climate change might have on space junk, author Ingrid Cnossen, a NERC independent research fellow at the British Antarctic Survey, modeled Earth’s entire atmosphere up to 310 miles (500 km). He then simulated the evolution of this atmosphere between 2015 and 2070. The simulation factored in CO2 and other greenhouse gas trends, historical changes in the Earth’s magnetic field, and solar cycle influences to create a realistic projection.

“The changes we saw between the climate in the upper atmosphere over the last 50 years and our predictions for the next 50 are a result of CO2 emissions,” Cnossen said in a press release. “It is increasingly important to understand and predict how climate change will impact these regions, particularly for the satellite industry and the policymakers who are involved with setting standards for that industry.”

Overall, Cnossen found that at an altitude of about 250 miles (400 km), the density of the thermosphere will decrease by 30 to 35 percent over the next few decades. Based on the results of another study (published in the JGR Atmospheres in 2021), such a significant reduction in the density of the thermosphere would increase the lifetime of objects in LEO by 30 percent compared to 2000.

And according to the 2021 study, a 30 percent reduction in thermosphere density is likely, even if humanity limits global warming to 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit (1.5 degrees Celsius), the current threshold set by the Paris Agreement.

“Space debris is becoming a rapidly growing problem for satellite operators due to the risk of collisions, which the long-term decline in upper atmosphere density is making even worse,” said Cnossen. “I hope this work will help to guide appropriate action to control the space pollution problem and ensure that the upper atmosphere remains a usable resource into the future.”