Key Takeaways:

On July 20, 1969, astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin undocked the lunar module from the command module Columbia. With astronaut Michael Collins remaining in lunar orbit, Armstrong and Aldrin used the lunar module to touch down in the Moon’s Sea of Tranquility.

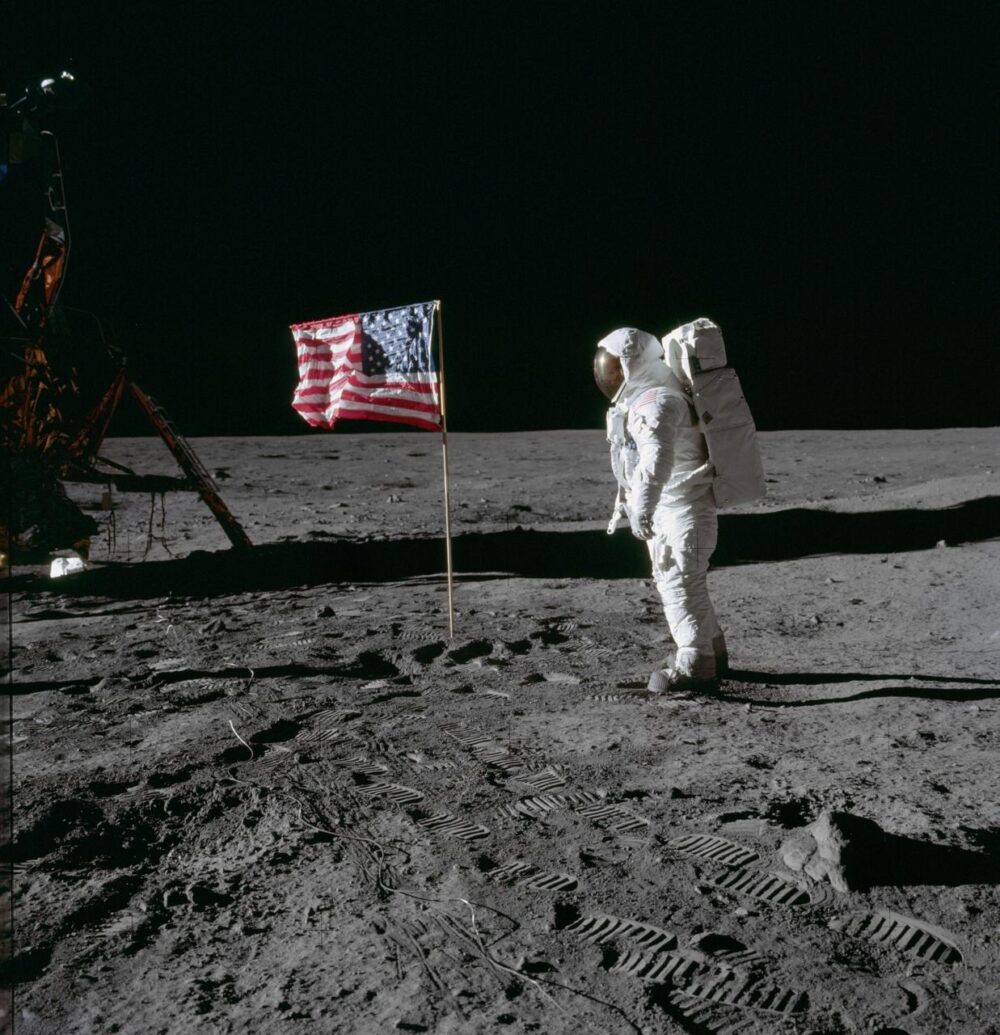

With the world watching the live transmission, Armstrong emerged from the module, becoming the first person to walk on the Moon. Aldrin followed 20 minutes later. The astronauts then spent the next 21 hours collecting Moon specimens while Collins kept the module in orbit.

After several hours of rest, the three began the journey back to Earth, and they returned home to a hero’s welcome. Although Armstrong was revered as the commander of the crew, he shied away from the attention and soon left NASA — opening up to biographers later. The Apollo 11 mission was one chapter in his eventful career as a pilot and astronaut, however here are five other details from his storied life you may not have known.

He had several close calls in flight

Many people remember Armstrong as the calm commander who landed Apollo 11 on the Moon in 1969. But it took him decades of flying to gain the needed experience to safely navigate the spacecraft.

Armstrong first received his pilot’s license at age 16. After graduating high school in Ohio in 1948, he attended Purdue University and had his tuition paid for by the Holloway Plan. The program had him attend his first two years at Purdue, then leave for two years of flight training and one year of aviator service with the U.S. Navy before returning to campus to finish his final two years.

While serving in the Korean War in 1951, Armstrong was flying low at 500 feet and 350 miles per hour. His plane hit a wire the North Koreans had strung up to damage low-flying planes. The wire ripped six feet off his right-wing. Armstrong flew his plane toward the ocean and away from enemy territory. He ejected over the water, but the winds dragged his parachute back toward land. To his surprise, an American military vehicle soon rumbled by and picked him up. The driver was a friend from flight school.

He had musical talents

While finishing his bachelor’s in aeronautical engineering, Armstrong also joined a fraternity and had a bit of fun. For the school’s Varsity Varieties, each fraternity had to present a short musical review. Armstrong twice wrote and directed his fraternity’s musical, including a version of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. It appears he paid too much attention to the musical, and he received a C that term in psychology for engineers, a C in aircraft vibrations and a D in electrical engineering.

Armstrong also met his first wife, Janet, at Purdue University where she was studying home economics. The couple wed in 1956, and Armstrong began working as a test pilot after graduation. They moved to California where Armstrong took a job at Edwards Air Force Base. Whenever he flew over their house, Armstrong would tip the plane wings to say “hello” to his wife and young son below.

He was a private person

Armstrong’s second child, Karen, died at the age of three in 1962. She had a tumor on her brain stem and later died of complications from the illness. Friends and co-workers remembered he aged quickly during this time and kept quiet about his loss. One friend from Purdue recalled he returned to Indiana for the school’s homecoming events. Their group of friends met for cocktails, and Armstrong broke down after seeing a friend’s young daughter in her green party dress.

Soon after his daughter’s death, Armstrong decided to apply to a new NASA space project. When NASA first convened Project Mercury to pursue human space flight, Armstrong was ineligible because he was a civilian, not a military pilot. In 1962, NASA started a new project and invited civilian pilots to apply. Armstrong initially hesitated, but he and his wife wanted to leave California after losing Karen.

He flew many, many missions

Armstrong was selected for NASA Astronaut Corps in September 1962, but he wasn’t considered NASA’s top guy. He flew his first mission as backup crew in 1965. He continued to serve on crews for space flights until November 1967 when he was selected to command the Apollo 11 on a lunar mission.

The White House wanted the commander to be a civilian, and NASA leaders picked Armstrong both as the commander and the first one to step out of the lunar module and onto the Moon dust. Many people suspected the higher ups chose Armstrong due to his likable persona. Armstrong was known for his quiet confidence, and he never took any shortcuts on his way to making history.

When Armstrong walked on the Moon on July 21, 1969, he said, “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.” He later claimed he said “a man” and the tape has been analyzed over the years to see if an ‘a’ was indeed present.

He still had to defend his master’s thesis

After his historic Moonwalk, Armstrong received invitations to meet with dignitaries worldwide. He became a household name, but he still had to impress his thesis committee the hard way.

Armstrong had completed his coursework at the University of Southern California for a master’s in aeronautical engineering while still working as a test pilot in California. In 1970, he returned to USC and successfully passed an oral defense of his thesis.

Armstrong left NASA in 1971, moved his family back to Ohio and took a professor position at the University of Cincinnati, where he remained for the next eight years. He remained connected with NASA and he served on various commissions, including the one that investigated the explosion of the Space Shuttle Challenger.

He continued to fly well into his 70s. When he died at the age of 82 in 2012, he donated many of his personal papers to Purdue University, including the staggering 70,000 pieces of fan mail.