New observations from Suzaku, a joint Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) and NASA X-ray observatory, have challenged scientists’ conventional understanding of white dwarfs. Observers had believed white dwarfs were inert stellar corpses that slowly cool and fade away, but the new data tell a completely different story.

At least one white dwarf, known as AE Aquarii, emits pulses of high-energy (hard) X-rays as it whirls around on its axis. “We’re seeing behavior like the pulsar in the Crab Nebula, but we’re seeing it in a white dwarf,” says Koji Mukai of NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. The Crab Nebula is the shattered remnant of a massive star that ended its life in a supernova explosion. “This is the first time such pulsar-like behavior has ever been observed in a white dwarf.”

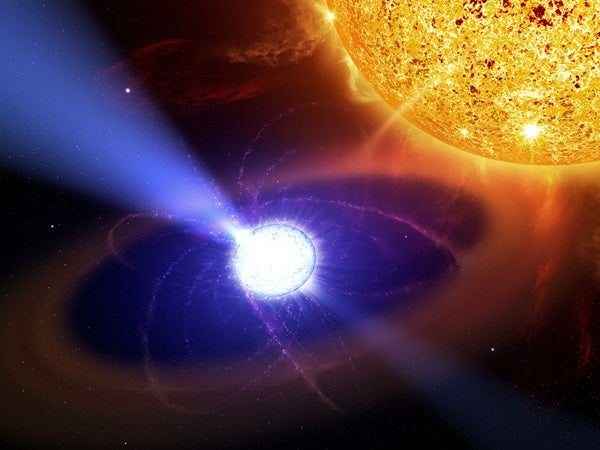

White dwarfs and pulsars represent distinct classes of compact objects that are born in the wake of stellar death. A white dwarf forms when a star similar in mass to the Sun runs out of nuclear fuel. As the outer layers puff off into space, the core gravitationally contracts into a sphere about the size of Earth, but with roughly the mass of the Sun. The white dwarf starts off scorching hot from the star’s residual heat. But with nothing to sustain nuclear reactions, it slowly cools over billions of years, eventually fading to near invisibility as a black dwarf.

A pulsar is a type of neutron star, a collapsed core of an extremely massive star that exploded in a supernova. Whereas white dwarfs have incredibly high densities by earthly standards, neutron stars are even denser, cramming roughly 1.3 solar masses into a city-sized sphere. Pulsars give off radio and X-ray pulsations in lighthouse-like beams.

Some white dwarfs, including AE Aquarii, spin very rapidly and have magnetic fields millions of times stronger than Earth’s. These characteristics give them the energy to generate cosmic rays.

To find out if this is happening, Terada and his colleagues targeted AE Aquarii with Suzaku in October 2005 and October 2006. The white dwarf resides in a binary system with a normal companion star. Gas from the star spirals toward the white dwarf and heats up, giving off a glow of low-energy (soft) X-rays. But Suzaku also detected sharp pulses of hard X-rays. After analyzing the data, the team realized that the hard X-ray pulses match the white dwarf’s spin period of once every 33 seconds.

The hard X-ray pulsations are very similar to those of the pulsar in the center of the Crab Nebula. In both objects, the pulses appear to be radiated like a lighthouse beam, and a rotating magnetic field is thought to be controlling the beam. Astronomers think that the extremely powerful magnetic fields are trapping charged particles and then flinging them outward at near-light speed. When the particles interact with the magnetic field, they radiate X-rays.

“AE Aquarii seems to be a white dwarf equivalent of a pulsar,” says Terada. “Since pulsars are known to be sources of cosmic rays, this means that white dwarfs should be quiet but numerous particle accelerators, contributing many of the low-energy cosmic rays in our galaxy.”

Launched in 2005, Suzaku is the fifth in a series of Japanese satellites devoted to studying celestial X-ray sources. Managed by JAXA, this mission is a collaborative effort between Japanese universities and institutions and Goddard.