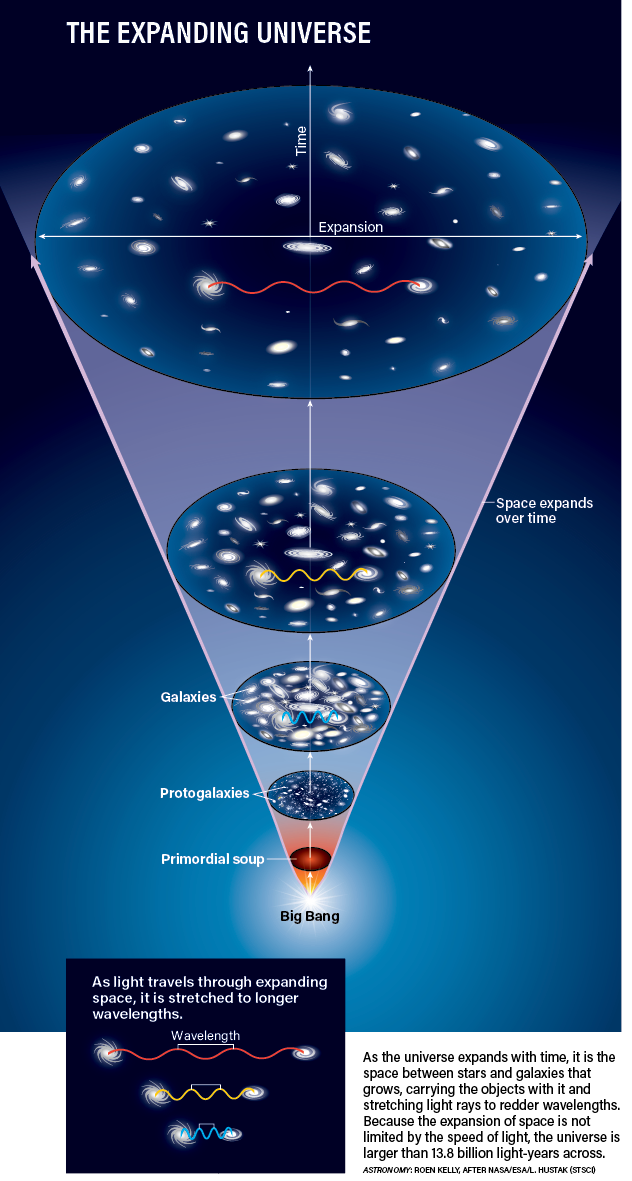

In a 1998 research breakthrough, Saul Perlmutter of the University of California, Berkeley, and his colleagues in the Supernova Cosmology Project found the expansion rate of the universe is accelerating.

Perlmutter and his team made the discovery by observing distant type Ia supernovae, whose brightnesses are well known, at different distances. His team made observations in conjunction with a team led by Brian Warner of the Mt. Stromlo-Siding Spring Observatories. This astonishing finding contradicts conventional wisdom, which suggests the universal expansion rate of galaxies away from each other is constant. Several implications follow the new finding, the most significant of which has turned cosmology on its head.

Bringing the universe to your door. We’re excited to announce Astronomy magazine’s new Space and Beyond subscription box – a quarterly adventure, curated with an astronomy-themed collection in every box. Learn More >>.

In May 1999, Perlmutter and his colleagues published a paper in Science magazine that outlined their ideas about a newly understood force in the universe — dark energy. “The universe is made up mostly of dark matter and dark energy,” wrote Perlmutter. Astronomers now think 68.3 percent of the mass-energy content of the cosmos consists of this dark energy and that it is the force accelerating the universe’s expansion. If dark energy is as dominant as astronomers believe it is, it will eventually force the universe into a cold, dark, ever-expanding end to space and time — the universe will end with a whimper, not with a bang.

Dark energy, now that it is known to exist, has come to the fore as one of science’s great mysteries. Although astronomers don’t yet know exactly what it is, three leading contenders offer possible explanations.

The first is the cosmological constant, or a static field of fixed energy, proposed by Albert Einstein (and which he later declared his biggest blunder). A second possibility is quintessence, a dynamic, scalar field of energy that varies through time and space.

The third possibility is that dark energy doesn’t exist; what astronomers observe with distant supernovae represents a breakdown of Einsteinian gravitational physics that has yet to be explained. A fourth possibility could be something we don’t yet understand.

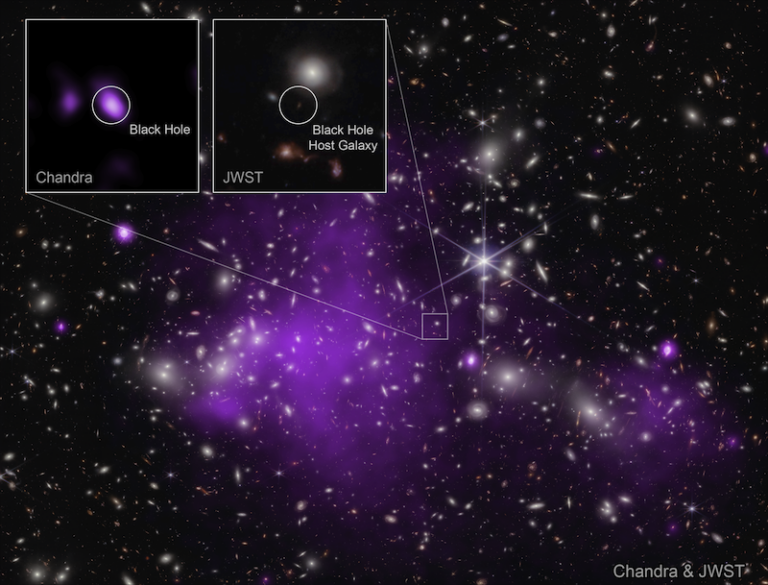

Determining what dark energy is will be far more complex than the discovery of the accelerating universe. Astronomers are using the Hubble Space Telescope to “push back to higher redshifts to measure the onset of acceleration,” says Adam Riess of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore. One important moment to focus on is the so-called transition point, the time when dark-energy acceleration overtook the normal pull of gravity and became the dominant force in the universe. This probably happened about 5 billion years ago, according to Riess.

Research on type Ia supernovae must continue to get a handle on this question. Could the reliability of type Ia supernovae come into question? The fact that not as many heavy metals existed in the very early universe could influence the brightnesses of these objects and throw astronomers’ observations off the mark.

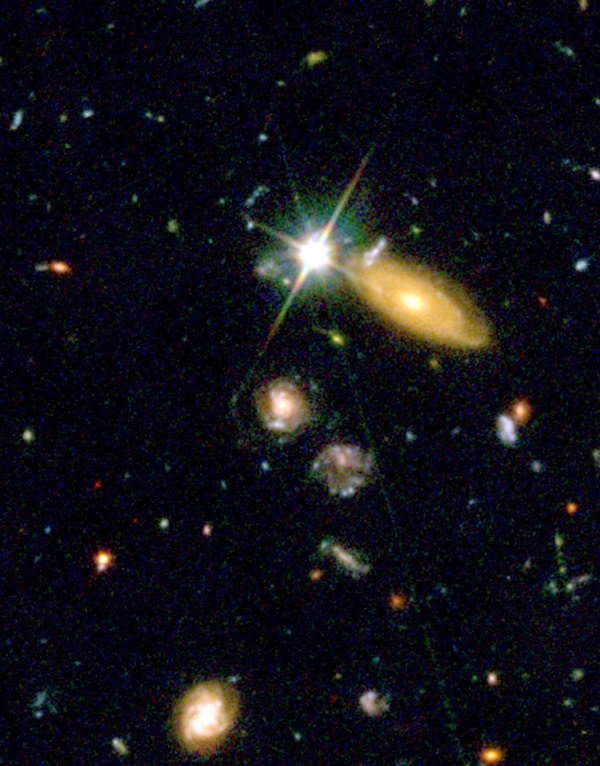

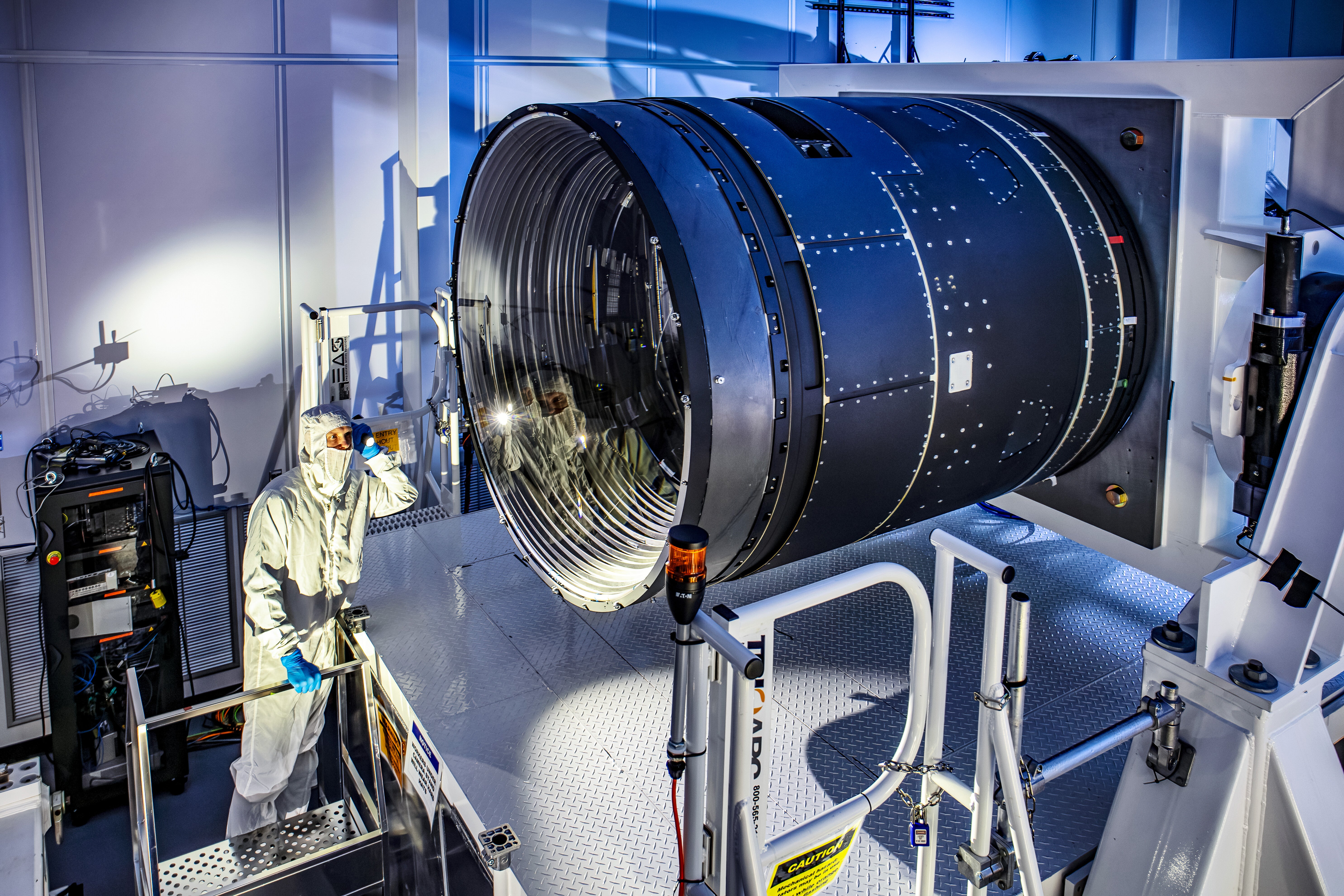

Other techniques will also come into play. Astronomers will observe galaxy clusters to see how their densities vary with distance. This could relate to whether gravity or dark energy dominated at certain times in the cosmos’ past. Cosmologists will also study gravitational lenses for clues to dark energy’s existence in the distortion patterns visible in these optical illusions. This pioneering technique, developed by the University of Pennsylvania’s Gary Bernstein, is in its infancy. “Right now,” says Bernstein, “we’re just starting to measure dark energy, but the more galaxies we get, the better we’ll do. The goal is to see as much sky as possible.”

The era of dark energy has just begun. Although no one yet knows what it is, astronomers think it represents an essential part of understanding the universe. Vast amounts of research will focus on dark energy in the years to come.