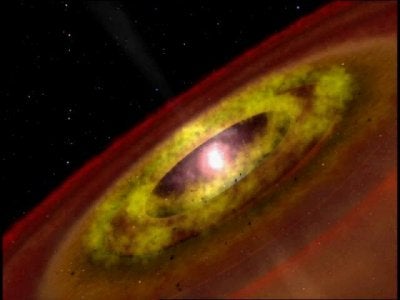

One of the major aspirations of modern astronomy is to capture the feeble light from Earth-sized planets orbiting distant stars. Taking a giant step closer to this lofty goal, a team of astronomers has combined the infrared light collected by two of the world’s largest observatories and detected a ring of gas and dust swirling around a star more than 450 light-years distant.

By linking the twin 10-meter Keck telescopes on Mauna Kea in Hawaii in October 2002 and February 2003, the astronomers made detailed measurements of the young star DG Tau and its surrounding disk of hot material. The infrared observations reveal that, while the orbiting disk extends more than 4.5 billion miles from the star (as expected), its inner edge surprisingly lies at least 11 million miles from the central star.

Of the more than 100 extrasolar planets discovered, about a quarter of them lie within 10 million miles of their host star. However, DG Tau has no protoplanetary material that close to itself. The larger-than-anticipated gap between DG Tau and its disk leads astronomers to speculate that either DG Tau’s disk is unusually far or that close-in planets have formed farther from their stars and eventually migrated inward.

“Studies like this teach us more about how stars form … and how planets eventually form in disks around stars,” states Rachel Akeson, leader of the research team and astronomer at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena.

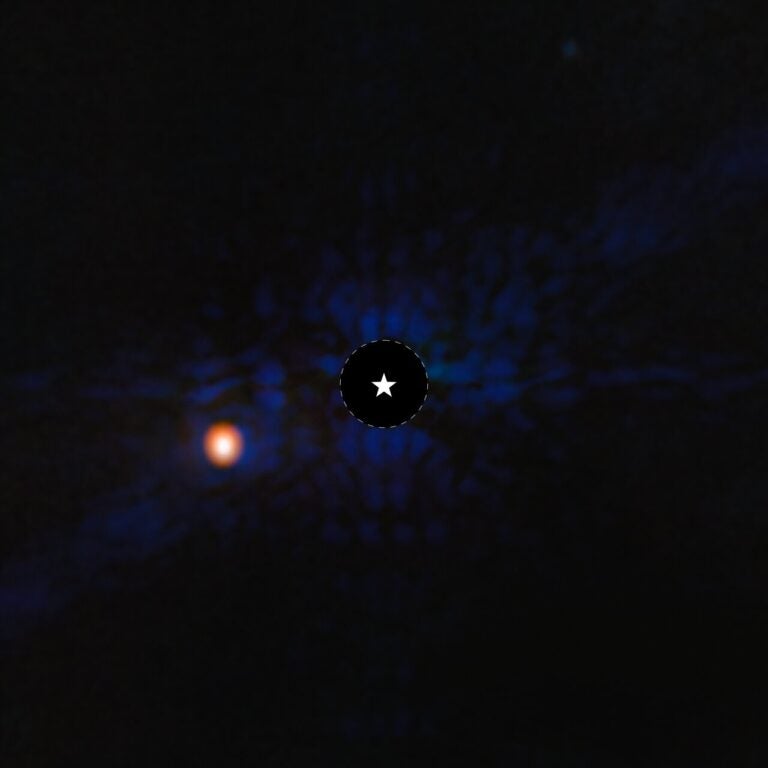

Thanks to an amazing technique called interferometry, the giant Keck mirrors work together as a single 85-meter glass, resolving finer detail than ever before. While observing the same object, the light collected by the individual telescopes is combined to create a constructive interference pattern. It would be like throwing one rock after another into a lake at just the right pace to create a set of ripples that join up and form a larger, more powerful set of waves.

The results, to be published in an upcoming issue of The Astrophysical Journal Letters, are the first published science observations by the Keck Interferometer. These findings also represent the first complete scientific study using an interferometer in combination with adaptive optics.