A new, nearby exoplanet could be just the boilerplate needed to find out if life could exist in untold numbers of star systems.

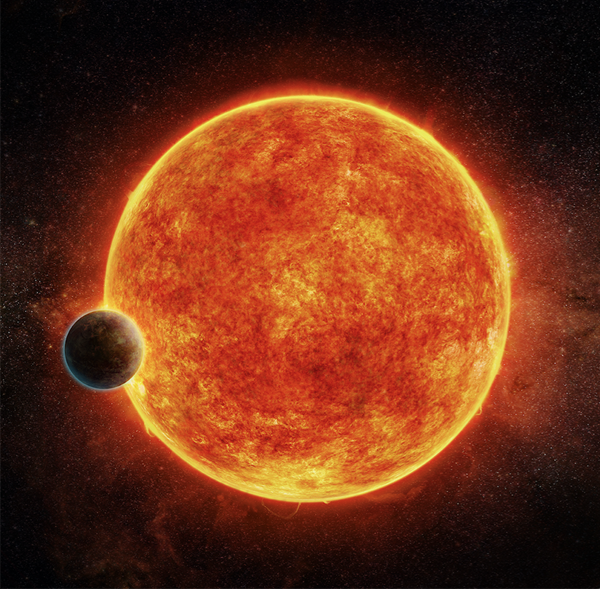

The planet, LHS 1140b, is 49 light years away. It orbits a small M-dwarf star every 24 days. The planet itself is 1.4 times larger and 6.6 times more massive than Earth, and the principal investigators of the study published today in Nature believe it to be rocky.

Our list of exoplanets is long — nearly 3,500 strong, with new planets coming every week. But the list of potentially habitable exoplanets is much shorter, topping out around a dozen. Most on that list are around M-dwarfs like LHS 1140. That’s because they’re the most abundant stars in the galaxy and some of the easier stars to capture transit signals from.

A planet is considered habitable when it’s in an area where liquid water might exist. But there’s a problem with planets around M-dwarfs, also known as red dwarfs: Tiny red dwarfs start out as furious flare machines, which could violently strip away primordial atmospheres around recently formed planets. And this could happen on the timescale of 3 billion years.

“There has been lots of debate about whether these planets can maintain a magnetic field (and if that’s important for habitability) and if M-dwarf planets lose their atmospheres in their host star’s active youth,” principal investigator Jason Dittman of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics told Astronomy. “This debate definitely isn’t settled, and there are compelling reasons why these planets might lose their atmospheres and there are also ways that you can imagine it can hold onto its atmosphere.”

There’s been compelling evidence lately that some of these planets around red dwarfs could, in fact, retain an atmosphere.That’s the case of GJ 1132b, a hellish world with Venus-like temperatures around an M-dwarf star that, despite all odds, seems to hold on to an atmosphere.

But an atmosphere around a habitable M-dwarf planet has never been spotted. LHS 1140b could provide an opportunity for some of the first observations. Unlike TRAPPIST-1 and Proxima Centauri, two stars that host planets in the habitable zone but have active flares that could ruin the chances their planets have atmospheres, LHS 1140 is a relatively calm, older star. If a planetary atmosphere managed to form, it could still survive today.

This also makes studying signals from the planets easier than around more active M-dwarfs. Modern telescopes like the Giant Magellan Telescope and Hubble Space Telescope might even be capable of spotting oxygen in the atmosphere of LHS 1140b. Indeed, Hubble has already completed one observation campaign with a few more to follow. If either of those telescopes can’t quite suss it out, future telescopes like the James Webb Space Telescope might make it easier.

If an atmosphere is spotted, it may help settle the great debate over whether M-dwarf planets can hold onto their atmospheres long enough to sustain life.

“I think that even during the star’s active early lifetime that water can possibly survive to the present day on these planets,” Dittman says. “We don’t know how much water they start with, so it’s perfectly feasible that these planets lost lots of water early on, but still managed to hold on to a little bit of water today.”