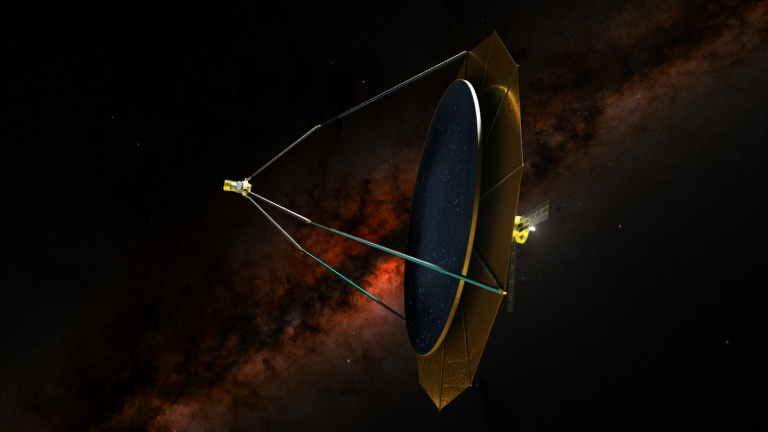

The spacecraft, dubbed al-Amal (Hope), launched from Japan’s Tanegashima Space Center on July 20 (local time). The historic launch kicked off the first interplanetary mission from an Arab nation, and Hope’s arrival at the Red Planet is set to coincide with 50th anniversary of the Emirates’ independence.

Are you ready to take a closer look at Mars? Check out our free downloadable eBook: Mars: Exploring the Red Planet.

Opening a window into Mars’ atmosphere

Hope will build on the legacy of NASA’s Mars Atmosphere and Volatile EvolutioN (MAVEN) orbiter, which is still functioning in orbit around Mars. Among other things, MAVEN revealed just how quickly the solar wind stripped Mars of its primordial atmosphere. And one goal of Hope is to answer lingering questions about how the Sun continues to affect Mars’ atmosphere on a global scale today.

To that end, Hope carries three instruments: a digital imager that will measure water ice and ozone in Mars’ lower atmosphere; an infrared spectrometer that will measure the global distribution of dust, ice clouds, and water vapor in Mars’ lower atmosphere; and a spectrometer that will measure the variability of hydrogen and oxygen in Mars’ upper atmosphere.

Over the course of about 10 days, Hope will collect atmospheric data covering the entire planet at varying local times of day, says Pete Withnell of the University of Colorado at Boulder, the mission’s program manager. This will, for the first time, enable scientists to track and understand the daily cycle of Mars’ temperature, water vapor, and dust, he says.

Previous missions to Mars have provided data at either fixed local times (from orbiters) or at mostly fixed locations on the surface (from rovers), says Withnell. While these missions have provided a wealth of knowledge, questions about the overall climate of Mars and the behavior of its atmosphere remain unanswered, he says. Through EMM, Withnel adds, scientists will finally be able to pull together a global understanding of the Red Planet.

By simultaneously observing both Mars’ lower and upper atmosphere, and by observing them together at all times of day, researchers will get a better understanding of the coupling between the two layers of the planet’s atmosphere, explains Bruce Jakosky, a planetary scientist at the University of Colorado at Boulder and an EMM science team member. Because this coupling passes gases from the lower atmosphere to the upper atmosphere that are subsequently lost to space, he says, the team expects the results to have an impact on our understanding of Mars’ long-term atmospheric evolution.

By better understanding Mars’ changing atmosphere, researchers hope to gain insight into how ancient Mars turned from what may have been an ocean-rich Eden into the barren desert world with an extremely thin atmosphere that it is today.

Surprisingly, the mission’s biggest technical challenge —so far — had little to do with design and engineering of the spacecraft itself. The most challenging hurdle was simply getting the spacecraft to the Japanese launch site in the middle of a global pandemic, says Omran Sharaf, EMM’s project director.

The researchers did not expect the routine transfer of Hope from Dubai to Tanegashima to become such a mission-critical race against time, but the COVID-19 pandemic forced airport closures, says Sharaf, which greatly complicated its journey to the launch pad.

Hope inspires hope for STEM students

As for the mission’s impact on science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) and aerospace studies in the UAE, Sharaf says EMM has already inspired Emiratis who want to pursue aerospace engineering and planetary science.

The UAE is now offering space systems engineering degrees in universities — which wasn’t the case when EMM was first announced in 2014, says Sharaf. The country is also seeing a tremendous boost in universities offering a wide variety of STEM degrees, as well as an uptick in students switching majors from other subjects to science, adds Sharaf.

All this is in addition to the UAE’s existing Arab Space Pioneer program, which invites talented young people from around the Arab world to the Emirates to learn about satellite engineering and space sciences.

“Our goal is less [to become] a major player than [it is] to become a major collaborator,” says Sharaf. “We’re interested in fostering and encouraging creative and beneficial collaborations, rather than aiming for preeminence. We’d like to see the Emirates as a hub and destination for global talent in space research.”