Using ESO’s Very Large Telescope Interferometer, astronomers have probed the inner parts of the disc of material surrounding a young stellar object, witnessing how it gains its mass before becoming an adult.

The astronomers had a close look at the object known as MWC 147, lying about 2,600 light-years away towards the constellation of Monoceros (the Unicorn). MWC 147 belongs to the family of Herbig Ae/Be objects. These have a few times the mass of our Sun and are still forming, increasing in mass by swallowing material present in a surrounding disc.

MWC 147 is less than half a million years old. If one associated the middle-aged, 4.6 billion year old Sun with a person in his early forties, MWC 147 would be a 1-day-old baby.

The morphology of the inner environment of these young stars is however a matter of debate and knowledge of it is important to better understand how stars and their cortege of planets form.

Astronomers have used the four 8.2-meter Unit Telescopes of ESO’s Very Large Telescope to this purpose, combining the light from two or three telescopes with the MIDI and AMBER instruments.

“With our VLTI/MIDI and VLTI/AMBER observations of MWC 147, we combine, for the first time, near- and mid-infrared interferometric observations of a Herbig Ae/Be star, providing a measurement of the disc size over a wide wavelength range,” says Stefan Kraus, lead author of the paper reporting the results. “Different wavelength regimes trace different temperatures, allowing us to probe the disc’s geometry on the smaller scale, but also to constrain how the temperature changes with the distance from the star.”

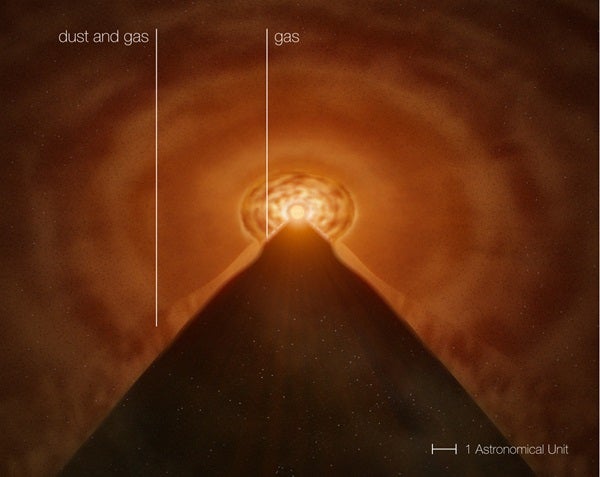

The near-infrared observations probe hot material with temperatures of up to a few thousand degrees in the innermost disc regions, while the mid-infrared observations trace cooler dust further out in the disc.

The observations show that the temperature changes with radius are much steeper than predicted by the currently favored models, indicating that most of the near-infrared emission emerges from hot material located very close to the star, that is, within one or two times the Earth-Sun distance (1-2 AU). This also implies that dust cannot exist so close to the star, since the strong energy radiated by the star heats and ultimately destroys the dust grains.

“We have performed detailed numerical simulations to understand these observations and reached the conclusion that we observe not only the outer dust disc, but also measure strong emission from a hot inner gaseous disc. This suggests that the disc is not a passive one, simply reprocessing the light from the star,” explains Kraus. “Instead, the disc is active, and we see the material, which is just transported from the outer disc parts towards the forming star.”

The best-fit model is that of a disc extending out to 100 AU, with the star increasing in mass at a rate of 7 millionths of a solar mass per year.

“Our study demonstrates the power of ESO’s VLTI to probe the inner structure of discs around young stars and to reveal how stars reach their final mass,” says Kraus.