Betelgeuse, a red supergiant in the constellation Orion, is one of the brightest stars in the night sky. It is also one of the biggest, being almost the size of the orbit of Jupiter — about 4.5 times the diameter of Earth’s orbit. The VLT image shows the surrounding nebula, which is much bigger than the supergiant itself, stretching 37 billion miles (60 billion kilometers) away from the star’s surface – about 400 times the distance of Earth from the Sun.

Red supergiants like Betelgeuse represent one of the last stages in the life of a massive star. In this short-lived phase, the star increases in size and expels material into space at a tremendous rate — it sheds immense quantities of material (about the mass of the Sun) in just 10,000 years.

The process by which material is shed from a star like Betelgeuse involves two phenomena. The first is the formation of huge plumes of gas (although much smaller than the nebula now imaged) extending into space from the star’s surface, previously detected using the NACO instrument on the VLT. The other, which is behind the ejection of the plumes, is the vigorous up and down movement of giant bubbles in Betelgeuse’s atmosphere — like boiling water circulating in a pot.

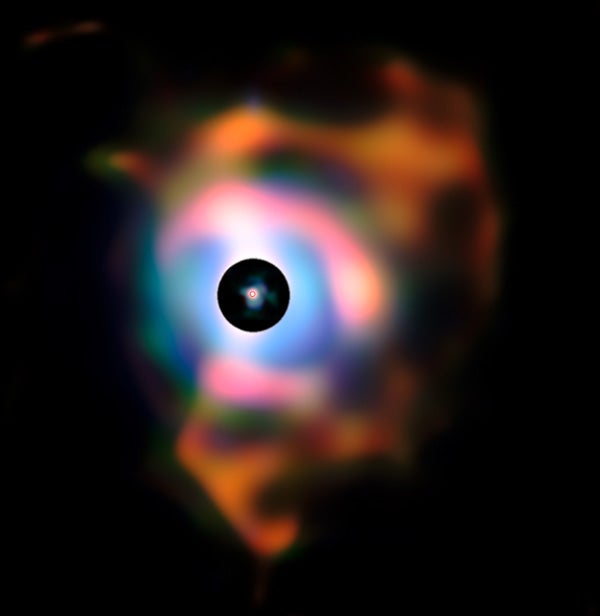

The new results show that the plumes seen close to the star are probably connected to structures in the outer nebula now imaged in the infrared with VISIR. The nebula cannot be seen in visible light, as the very bright Betelgeuse completely outshines it. The irregular, asymmetric shape of the material indicates that the star did not eject its material in a symmetric way. The bubbles of stellar material and the giant plumes they originate may be responsible for the clumpy look of the nebula.

The material visible in the new image is most likely made of silicate and alumina dust. This is the same material that forms most of the crust of Earth and other rocky planets. At some time in the distant past, the silicates of Earth were formed by a massive (and now extinct) star similar to Betelgeuse.

In this composite image, the earlier NACO observations of the plumes are reproduced in the central disk. The small red circle in the middle has a diameter about 4.5 times that of Earth’s orbit and represents the location of Betelgeuse’s visible surface. The black disk corresponds to a bright part of the image that was masked to allow the fainter nebula to be seen. The VISIR images were taken through infrared filters sensitive to radiation of different wavelengths, with blue corresponding to shorter wavelengths and red to longer. The field of view is 5.63 by 5.63 arcseconds.

Betelgeuse, a red supergiant in the constellation Orion, is one of the brightest stars in the night sky. It is also one of the biggest, being almost the size of the orbit of Jupiter — about 4.5 times the diameter of Earth’s orbit. The VLT image shows the surrounding nebula, which is much bigger than the supergiant itself, stretching 37 billion miles (60 billion kilometers) away from the star’s surface – about 400 times the distance of Earth from the Sun.

Red supergiants like Betelgeuse represent one of the last stages in the life of a massive star. In this short-lived phase, the star increases in size and expels material into space at a tremendous rate — it sheds immense quantities of material (about the mass of the Sun) in just 10,000 years.

The process by which material is shed from a star like Betelgeuse involves two phenomena. The first is the formation of huge plumes of gas (although much smaller than the nebula now imaged) extending into space from the star’s surface, previously detected using the NACO instrument on the VLT. The other, which is behind the ejection of the plumes, is the vigorous up and down movement of giant bubbles in Betelgeuse’s atmosphere — like boiling water circulating in a pot.

The new results show that the plumes seen close to the star are probably connected to structures in the outer nebula now imaged in the infrared with VISIR. The nebula cannot be seen in visible light, as the very bright Betelgeuse completely outshines it. The irregular, asymmetric shape of the material indicates that the star did not eject its material in a symmetric way. The bubbles of stellar material and the giant plumes they originate may be responsible for the clumpy look of the nebula.

The material visible in the new image is most likely made of silicate and alumina dust. This is the same material that forms most of the crust of Earth and other rocky planets. At some time in the distant past, the silicates of Earth were formed by a massive (and now extinct) star similar to Betelgeuse.

In this composite image, the earlier NACO observations of the plumes are reproduced in the central disk. The small red circle in the middle has a diameter about 4.5 times that of Earth’s orbit and represents the location of Betelgeuse’s visible surface. The black disk corresponds to a bright part of the image that was masked to allow the fainter nebula to be seen. The VISIR images were taken through infrared filters sensitive to radiation of different wavelengths, with blue corresponding to shorter wavelengths and red to longer. The field of view is 5.63 by 5.63 arcseconds.