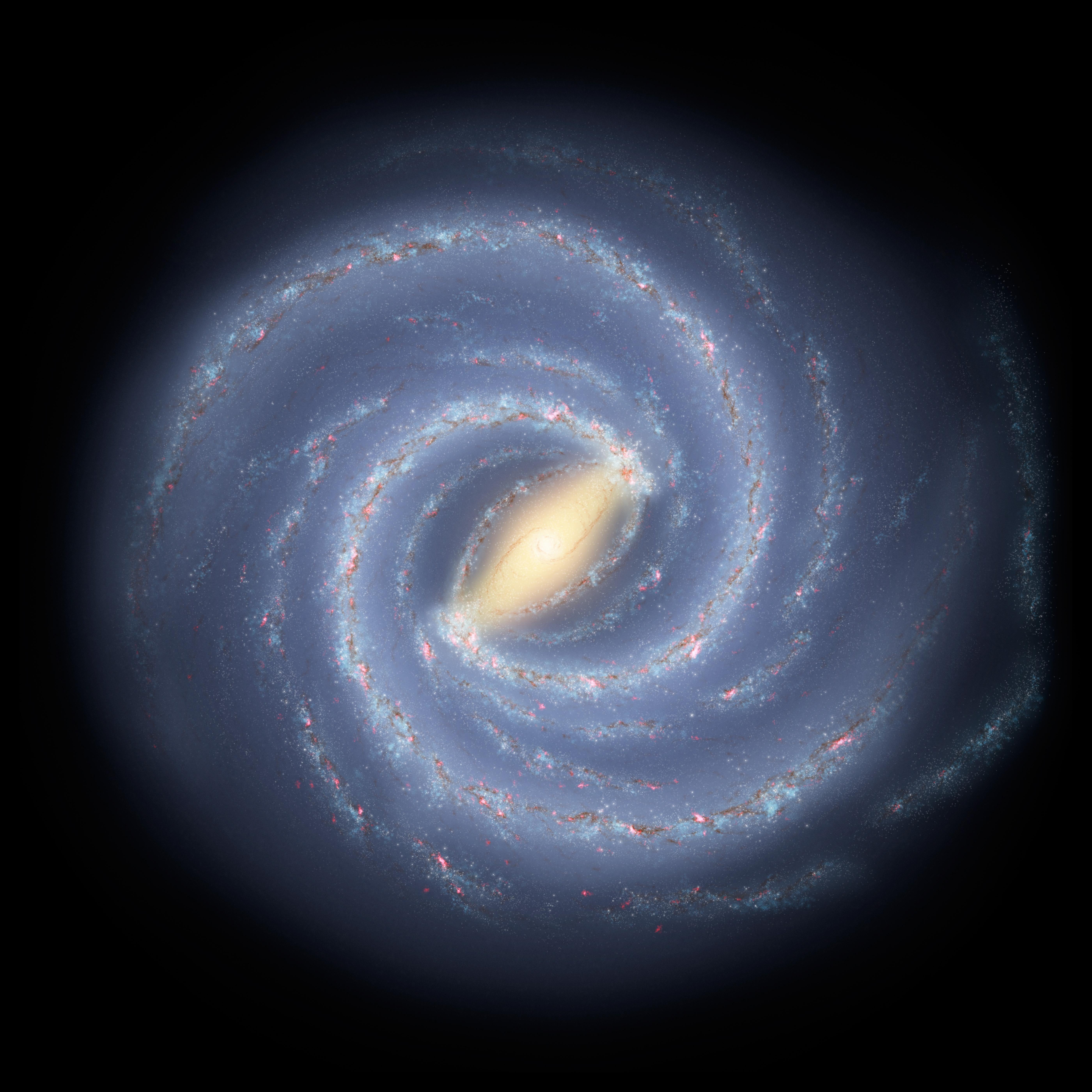

The Andromeda Galaxy is approaching the Milky Way at nearly a quarter million miles per hour. It is the closet major galaxy to our Milky Way and is the most distant thing you can see with the naked eye at 2.5 million light years away. Absolute chaos will begin as the two galaxies approach each other, eventually becoming Milkomeda. Everything will look like a massive pinball game, with huge amounts of rocks, dust, asteroids, planets, and stars being thrown in all directions.

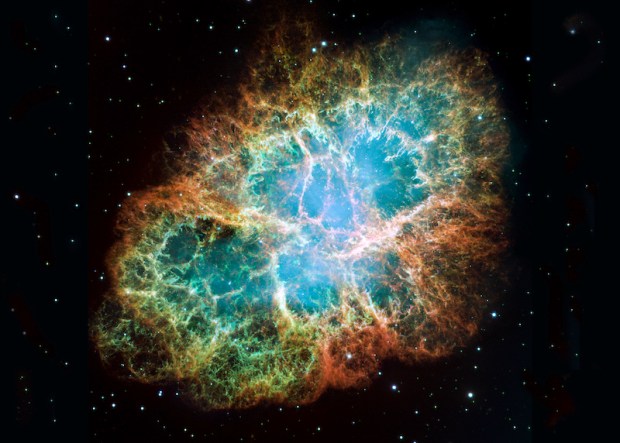

Until 2012, it was not known whether the collision was definitely going to happen or not. Researchers, using Hubble to track the motions of stars in Andromeda with unprecedented accuracy, concluded the galaxies would collide in about 4 billion years. Such collisions are relatively common, considering galaxies long lifespans. According to simulations, the remnant will look like a giant elliptical galaxy, which is a blob-like galaxy without discernible spiral arms or an internal structure.

Andromeda galaxy contains about one trillion stars and the Milky Way contains about 300 billion. The stars involved are sufficiently far apart that it’s highly improbable that any of them will individually collide. For example, the nearest part of the Sun is Proxima Centauri, which is about 4.2 light years away. If the Sun were a ping pong ball, then Proxima Centauri would be a pea about 680 miles away. Although stars are more common near the centers of each galaxy, the average distance between stars is still 100 billion miles. That is like placing one ping-pong ball every two miles; thus, it’s extremely unlikely that any two stars from the merging galaxy would collide, but some stars might be ejected.

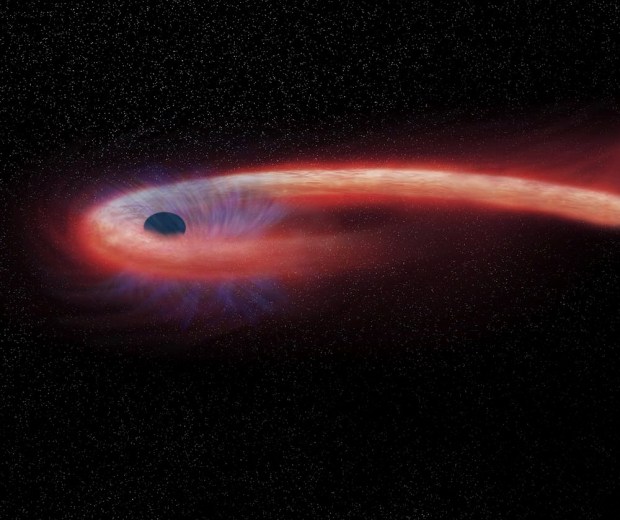

What happens to the black holes after the Andromeda and Milky Way collision?

The Milky Way and Andromeda each contain a central supermassive black hole. These black holes will eventually spiral into one another and converge near the center of the newly formed galaxy over a period that may take millions of years. When the supermassive black holes come within one light year of another, they will begin to strongly emit gravitational waves that will radiate further orbital energy until they merge completely. Gas taken up by the combined black holes could create an active galactic nucleus. If this happens it would release an inconceivable amount of energy.

OK, so what’s the future of our solar system?

Based on current calculations, scientists predict a 50% chance that in a merged galaxy the solar system will be swept out three times farther from the galactic core than its current position. Our galaxy is organized into spiral arms and the Sun is in a branch called the Orion Spur. If we were to be flung farther out, that means our solar system would land just at the fingertips of this arm. Scientists also predict sometime during the collision, there is a 12% chance that the solar system could be entirely ejected from the newly formed galaxy. For some reassurance, humanity would be long gone by then, of course. Such an event would actually have no adverse effect on the solar system and the chances of any sort of disturbance to the Sun or planets themselves may be remote, that is excluding planetary engineering.

By the time the two galaxies collide, the surface of the Earth will have already become far too hot for liquid water to exist, due to the gradually increasing luminosity of the Sun, ending all terrestrial life, but our planet will still be caught in the middle of this collision and its view of the universe will never be the same. If we could however see the night sky still, whether form the hellish perspective of Earth or from the far reaches of the outer solar system, Andromeda would be growing larger in the sky and eventually about 4 billion years from now, it could possibly stretch from horizon to horizon like a serene rainbow of dew.