Key Takeaways:

Between 2009 and 2011, researchers from the Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology (KIPAC) used Suzaku’s unique capabilities to map the distribution of iron throughout the Perseus Galaxy Cluster.

What they found is remarkable: Across the cluster, which spans more than 11 million light-years of space, the concentration of X-ray-emitting iron is essentially uniform in all directions.

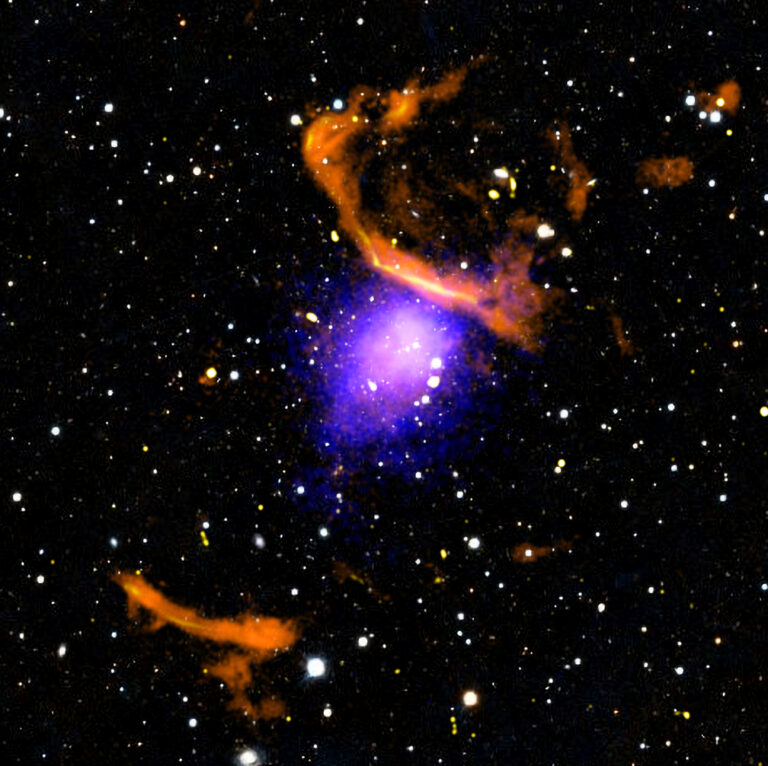

“This tells us that the iron — and by extension, other heavy elements — already was widely dispersed throughout the universe when the cluster began to form,” said Norbert Werner from KIPAC. “We conclude that any explanation of how this happened demands lead roles for supernova explosions and active black holes.”

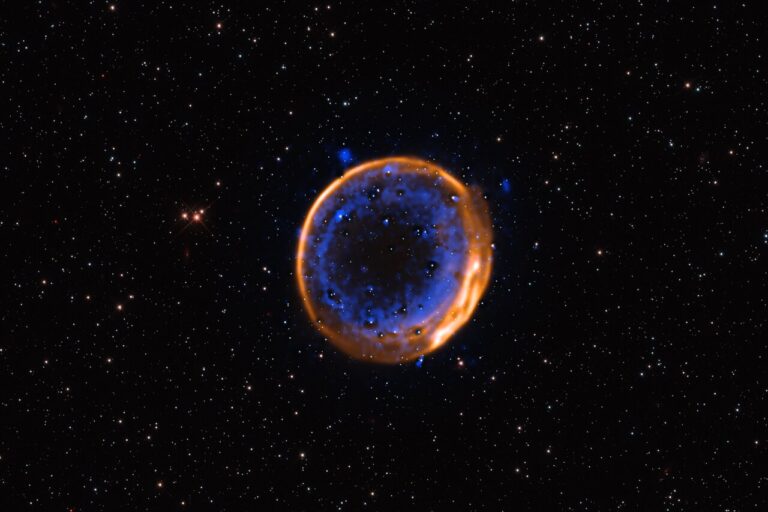

The most profligate iron producers are type Ia supernovae, which occur either when white dwarf stars merge or otherwise acquire so much mass that they become unstable and explode. According to the Suzaku observations, the total amount of iron contained in the gas filling the cluster amounts to 50 billion times the mass of our Sun, with about 60 percent of that found in the cluster’s outer half.

The team estimates that at least 40 billion type Ia supernovae contributed to the chemical “seeding” of the space that later became the Perseus Galaxy Cluster.

Making iron is one thing, while distributing it evenly throughout the region where the cluster formed is quite another. The researchers suggest that everything came together during one specific period of cosmic history.

Between about 10 and 12 billion years ago, the universe was forming stars as fast as it ever has. Abundant supernovae accompany periods of intense star formation, and the rapid-fire explosions drove galaxy-scale outflows. At the same time, supermassive black holes at the centers of galaxies were at their most active, rapidly accreting gas and releasing large amounts of energy, some of which drove powerful jets. Together, these galactic “winds” blew the chemical products of supernovae out of their host galaxies and into the wider cosmos.

Sometime later, in the regions of space with the largest matter densities, galaxy clusters formed, scooping up and mixing together the cosmic debris from regions millions of light-years across.

“If our scenario is correct, then essentially all galaxy clusters with masses similar to the Perseus cluster should show similar iron concentrations and smooth distributions far from the center,” said Ondrej Urban from KIPAC.

Galaxy clusters contain hundreds to thousands of galaxies, as well as enormous quantities of diffuse gas and dark matter, bound together by their collective gravitational pull.

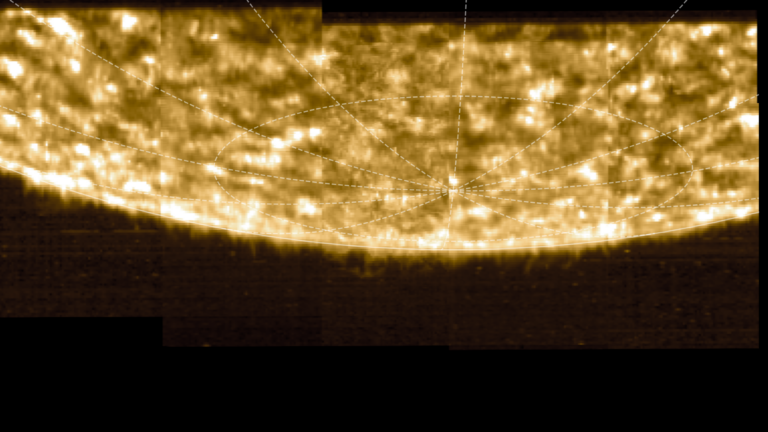

New gas entering the cluster falls toward its center, eventually moving fast enough to generate shock waves that heat the infalling gas. In the Perseus cluster, gas temperatures reach as high as 180 million degrees Fahrenheit (100 million degrees Celsius), so hot that the atoms are almost completely stripped of their electrons and emit X-rays.

The Perseus Galaxy Cluster, which is located about 250 million light-years away and named for its host constellation, is the brightest extended X-ray source beyond our galaxy and the brightest and closest cluster for which Suzaku has attempted to map outlying gas.

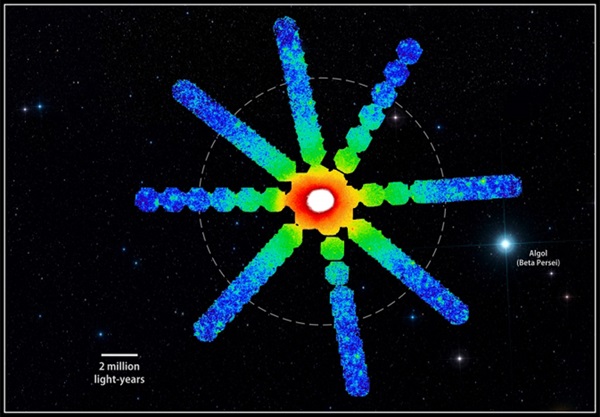

The team used Suzaku’s X-ray telescopes to make 84 observations of the Perseus cluster, resulting in radial maps along eight different directions. Thanks to the sensitivity of the spacecraft’s instruments, the researchers could measure the iron distribution of faint gas in the cluster’s outermost reaches, where new gas continues to fall into it.