Key Takeaways:

At first glance, a weather forecaster for Venus would have either a really easy or a really boring job, depending on your point of view. The climate on Venus is widely known to be unpleasant —at the surface, the planet roasts at more than 800° Fahrenheit (425° Celsius) under a suffocating blanket of sulfuric acid clouds and a crushing atmosphere more than 90 times the pressure of Earth’s. Intrepid future explorers should abandon any hope for better days, however, because it won’t change much.

“Any variability in the weather on Venus is noteworthy because the planet has so many features to keep atmospheric conditions the same,” said Tim Livengood, a researcher with the National Center for Earth and Space Science Education, Capitol Heights, Maryland, and now with the University of Maryland, College Park.

“Earth has seasons because its rotation axis is tilted by about 23°, which changes the intensity of sunlight and the length of the day in each hemisphere throughout the year,” explained Livengood, who is stationed at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “However, Venus has been tilted so much, it’s almost completely upside down, leaving it with a net tilt of less than 3° from the Sun, so the seasonal effect is negligible. Also, its orbit is even more circular than Earth’s, which prevents it from getting significantly hotter or cooler by moving closer to or farther away from the Sun. And while you might expect things to cool down at night — especially since Venus rotates so slowly that its night lasts almost 2 Earth months — the thick atmosphere and sulfuric acid clouds act like a blanket while winds move heat around, keeping temperatures pretty even. Finally, almost all the planet’s water has escaped to space, so you don’t get any storms or precipitation like on Earth where water evaporates and condenses as clouds.”

However, higher up, the weather gets more interesting, according to a new study of old data by NASA and international scientists. The team detected strange things going on in data from telescopic observations of Venus in infrared light at about 68 miles (110 kilometers) above the planet’s surface, in cold, clear air above the acid clouds, in two layers called the mesosphere and the thermosphere.

“Although the air over the polar regions in these upper atmospheric layers on Venus was colder than the air over the equator in most measurements, occasionally it appeared to be warmer,” said Theodor Kostiuk of Goddard. “In Earth’s atmosphere, a circulation pattern called a ‘Hadley cell’ occurs when warm air rises over the equator and flows toward the poles, where it cools and sinks. Since the atmosphere is denser closer to the surface, the descending air gets compressed and warms the upper atmosphere over Earth’s poles. We saw the opposite on Venus. In addition, although the surface temperature is fairly even, we’ve seen substantial changes — up to 54° Fahrenheit (about 30 kelvin change) — within a few Earth days in the mesosphere — thermosphere layers over low latitudes on Venus. The poles appeared to be more stable, but we still saw changes up to 27° Fahrenheit (about 15 K change).”

“The mesosphere and thermosphere of Venus are dynamically active,” said Guido Sonnabend of the University of Cologne, Germany. “Wind patterns resulting from solar heating and east to west zonal winds compete, possibly resulting in altered local temperatures and their variability over time.”

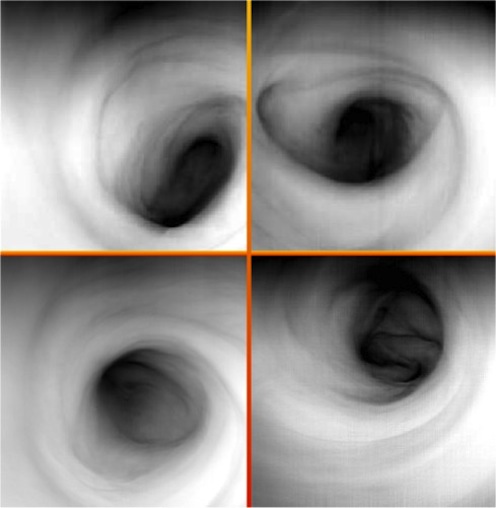

This upper atmospheric variability could have many possible causes, according to the team. Turbulence from global air currents at different altitudes flowing at more than 200 mph (300 km/h) in opposite directions could exchange hot air from below with cold air from above to force changes in the upper atmosphere. Also, giant vortexes swirl around each pole. They, too, could generate turbulence and change the pressure, causing the temperature to vary.

Because the atmospheric layers the team observed are above the cloud blanket, they may be affected by changes in sunlight intensity as day transitions to night, or as latitude increases toward the poles. These layers are high enough that they could even be affected by solar activity (the solar cycle), such as solar explosions called flares and eruptions of solar material called coronal mass ejections.

The team saw changes over periods spanning days, to weeks, to a decade. Temperatures measured in 1990–91 were warmer than in 2009. Measurements obtained in 2007 using Goddard’s Heterodyne Instrument for Planetary Wind and Composition (HIPWAC) observed warmer temperature in the equatorial region than in 2009. Having seen that the atmosphere can change, a lot more observations are needed to determine how so many phenomena can affect Venus’ upper atmosphere over different intervals, according to the team.

“In addition to all these changes, we saw warmer temperatures than those predicted for this altitude by the leading accepted model, the Venus International Reference Atmosphere model,” said Kostiuk. “This tells us that we have lots of work to do updating our upper atmospheric circulation model for Venus.”

Although Venus is often referred to as Earth’s twin because they are almost the same size, it ended up with a climate very different from Earth’s. A deeper understanding of Venus’ atmosphere will let researchers compare it to the evolution of Earth’s atmosphere, giving insight as to why Earth now teems with life while Venus suffered a hellish fate.

The team measured temperature and wind speeds in Venus’ upper atmosphere by observing an infrared glow emitted by carbon dioxide (CO2) molecules when they were energized by light from the Sun. Infrared light is invisible to the human eye and is perceived by us as heat, but it can be detected by special instruments. In the research, it appeared as a line on a graph from a spectrometer, an instrument that separates light into its component colors, each of which corresponds to a specific frequency. The width of the line revealed the temperature while shifts in its frequency gave the wind speed.

The researchers compared observations from 1990 and 1991 using Goddard’s Infrared Heterodyne Spectrometer instrument at NASA’s Infrared Telescope Facility on Mauna Kea, Hawaii, to observations from 2009 using the Cologne Tunable Heterodyne Infrared Spectrometer instrument at the National Optical Astronomy Observatory’s McMath Telescope at Kitt Peak, Arizona.