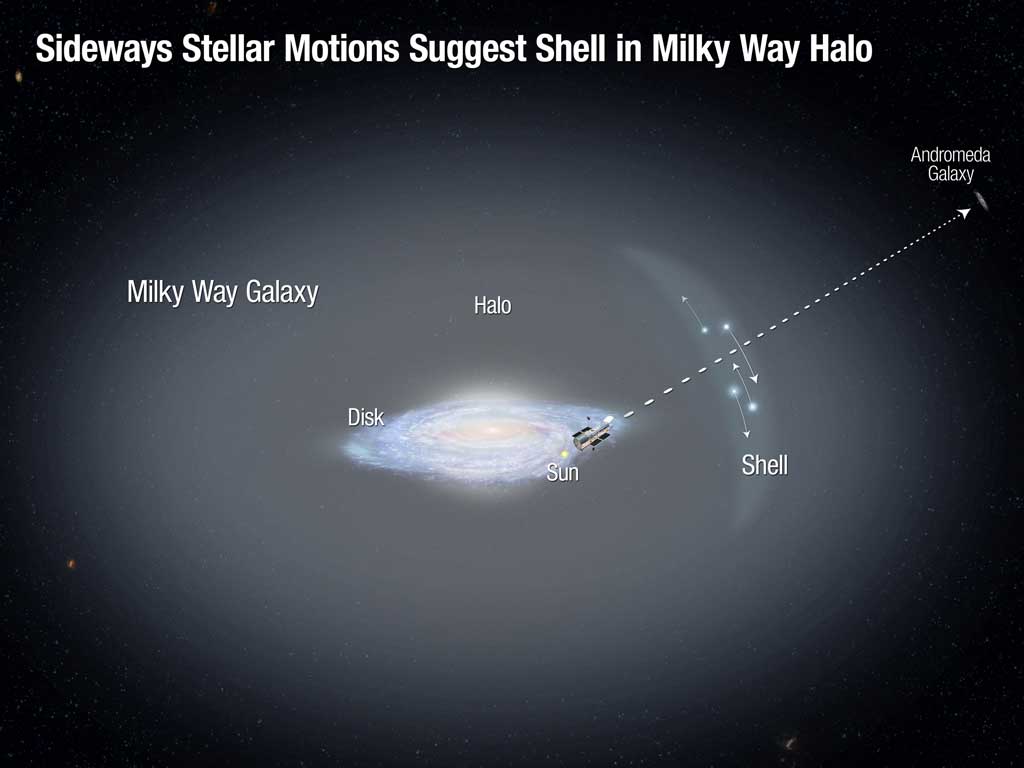

Researchers used Hubble to precisely measure, for the first time ever, the sideways motions of a small sample of stars located far from the galaxy’s center. Their unusual lateral motion is circumstantial evidence that the stars may be the remnants of a shredded galaxy that the Milky Way gravitationally ripped apart billions of years ago. These stars support the idea that the Milky Way grew, in part, through the accretion of smaller galaxies.

“Hubble’s unique capabilities are allowing astronomers to uncover clues to the galaxy’s remote past. The more distant regions of the galaxy have evolved more slowly than the inner sections. Objects in the outer regions still bear the signatures of events that happened long ago,” said Roeland van der Marel of the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore, Maryland.

The stars also offer a new opportunity for measuring the “hidden” mass of our galaxy, which is in the form of dark matter — an invisible form of matter that does not emit or reflect radiation. In a universe full of 100 billion galaxies, our Milky Way “home” offers the closest and, therefore, best site for detailed study of the history and architecture of a galaxy.

A team of astronomers led by Alis Deason of the University of California, Santa Cruz, and van der Marel identified 13 stars located roughly 80,000 light-years from the galaxy’s center. They lie in an outer halo of ancient stars that date back to the formation of our galaxy. The team was surprised to find that the stars showed more of a sideways, or tangential, amount of motion than they expected. This movement is different from what astronomers know about the halo stars near the Sun, which move predominantly in radial orbits. Stars in these orbits plunge toward the galactic center and travel back out again. The stars’ tangential motion can be explained if there is an over-density of stars at 80,000 light-years — like cars backing up on an expressway. This traffic jam would form a shell-like feature, like ones seen around other galaxies.

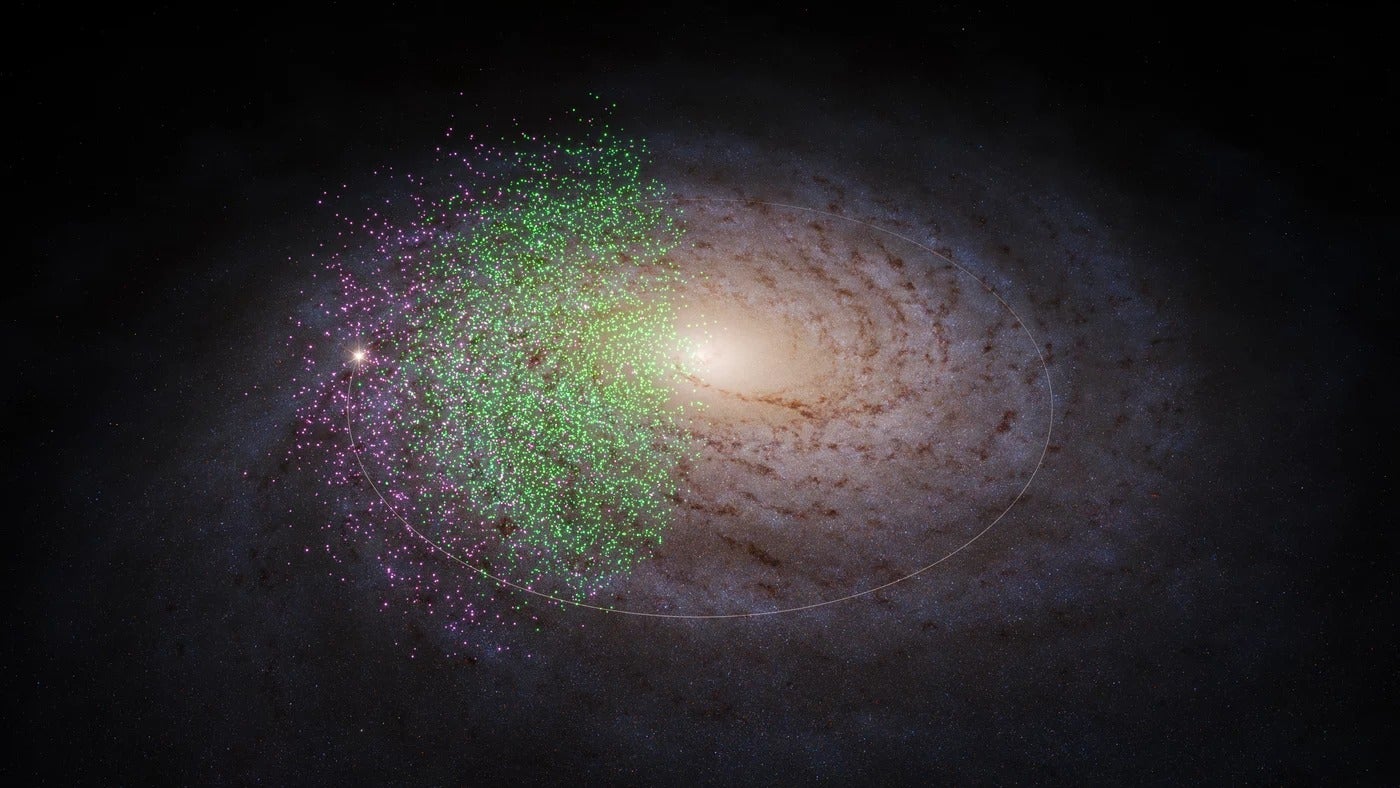

Deason and her team plucked the outer halo stars out of seven years’ worth of archival Hubble telescope observations of our neighboring Andromeda Galaxy (M31). In those observations, Hubble peered through the Milky Way’s halo to study the more distant galaxy’s stars, which are more than 20 times farther away. The Milky Way’s halo stars were in the foreground and considered as clutter for the study of M31. But to Deason’s study, they were pure gold. The observations offered a unique opportunity to look at the motion of Milky Way halo stars.

Finding the stars was meticulous work. Each Hubble image contained more than 100,000 stars. “We had to somehow find those few stars that actually belonged to the Milky Way halo,” van der Marel said. “It was like finding needles in a haystack.”

The astronomers identified the stars based on their colors, brightnesses, and sideways motions. The halo stars appear to move faster than M31’s stars because they are so much closer. Team member Sangmo Tony Sohn of STScI identified the halo stars and measured both the amount and direction of their slight sideways motion. The stars move on the sky only about one milliarcsecond a year, which would be like watching a golf ball on the Moon moving one foot per month. Nonetheless, this was measured with 5 percent precision.

“Measurements of this accuracy are enabled by a combination of Hubble’s sharp view, the many years’ worth of observations, and the telescope’s stability,” said van der Marel. “Hubble is located in the space environment, and it’s free of gravity, wind, atmosphere, and seismic perturbations.”

Stars in the inner halo have highly radial orbits. When the team compared the tangential motion of the outer halo stars with their radial motion, they were very surprised to find that the two were equal. Computer simulations of galaxy formation normally show an increasing tendency towards radial motion if one moves further out in the halo. These observations imply the opposite trend. The existence of a shell structure in the Milky Way halo is one plausible explanation of the researchers’ findings. Such a shell can form by accretion of a satellite galaxy. This is consistent with a picture in which the Milky Way has undergone continuing evolution over its lifetime due to the accretion of satellite galaxies.

The team compared their results with data of halo stars recorded in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. Those observations uncovered a higher density of stars at about the same distance as the 13 outer halo stars in their Hubble study. A similar excess of halo stars exists across the constellations Triangulum and Andromeda. Beyond that radius, the number of stars plummets.

Deason immediately thought the two results were more than just coincidence. “What may be happening is that the stars are moving quite slowly because they are at the apocenter, the farthest point in their orbit about the hub of our Milky Way,” Deason said. “The slowdown creates a pileup of stars as they loop around in their path and travel back towards the galaxy. So the in-and-out or radial motion decreases compared with their sideways or tangential motion.”

Shells of stars have been seen in the halos of some galaxies, and astronomers predicted that the Milky Way may contain them, too. But until now, there was limited evidence for their existence. The halo stars in our galaxy are hard to see because they are dim and spread across the sky.

Encouraged by this study, the team hopes to search for more distant halo stars in the Hubble archive. “These unexpected results fuel our interest in looking for more stars to confirm that this is really happening,” Deason said. “At the moment, we have quite a small sample. So we really can make it a lot more robust with getting more fields with Hubble.” The Andromeda observations only cover a small “keyhole view” of the sky.

The team’s goal is to put together a clearer picture of how the Milky Way formed. By knowing the orbits and motions of many halo stars, it will also be possible to calculate an accurate mass for the galaxy. “Until now, what we have been missing is the stars’ tangential motion, which is a key component,” Deason said. “The tangential motion will allow us to better measure the total mass distribution of the galaxy, which is dominated by dark matter. By studying the mass distribution, we can see whether it follows the same distribution as predicted in theories of structure formation.”