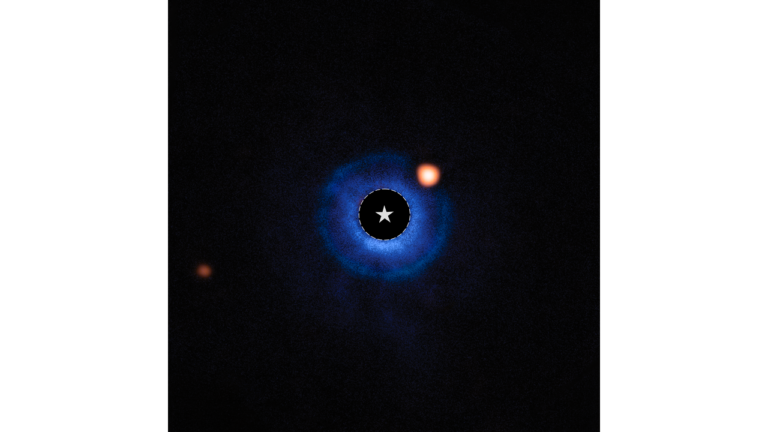

The planet is marked by high clouds in the west and clear skies in the east. Previous studies from Spitzer have resulted in temperature maps of planets orbiting other stars, but this is the first look at cloud structures on a distant world.

“By observing this planet with Spitzer and Kepler for more than three years, we were able to produce a very low-resolution ‘map’ of this giant gaseous planet,” said Brice-Olivier Demory of Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge.“We wouldn’t expect to see oceans or continents on this type of world, but we detected a clear, reflective signature that we interpreted as clouds.”

Kepler has discovered more than 150 exoplanets, which are planets outside our solar system, and Kepler-7b was one of the first. The telescope’s problematic reaction wheels prevent it from hunting planets any more, but astronomers continue to pore over almost four years’ worth of collected data.

Kepler’s visible-light observations of Kepler-7b’s moon-like phases led to a rough map of the planet that showed a bright spot on its western hemisphere. But these data were not enough on their own to decipher whether the bright spot was coming from clouds or heat. The Spitzer Space Telescope played a crucial role in answering this question.

Like Kepler, Spitzer can fix its gaze at a star system as a planet orbits around the star, gathering clues about the planet’s atmosphere. Spitzer’s ability to detect infrared light means it was able to measure Kepler-7b’s temperature, estimating it between 1500° and 1800° Fahrenheit (815° and 1000° Celsius). This is relatively cool for a planet that orbits so close to its star — within 0.06 astronomical unit — and, according to astronomers, too cool to be the source of light Kepler observed. Instead, they determined light from the planet’s star is bouncing off cloud tops located on the west side of the planet.

“Kepler-7b reflects much more light than most giant planets we’ve found, which we attribute to clouds in the upper atmosphere,” said Thomas Barclay from NASA’s Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California. “Unlike those on Earth, the cloud patterns on this planet do not seem to change much over time — it has a remarkably stable climate.”

The findings are an early step toward using similar techniques to study the atmospheres of planets more like Earth in composition and size.

“With Spitzer and Kepler together, we have a multi-wavelength tool for getting a good look at planets that are trillions of miles away,” said Paul Hertz, director of NASA’s Astrophysics Division in Washington, D.C. “We’re at a point now in exoplanet science where we are moving beyond just detecting exoplanets, and into the exciting science of understanding them.”

Kepler identified planets by watching for dips in starlight that occur as the planets transit, or pass in front of their stars, blocking the light. This technique and other observations of Kepler-7b previously revealed that it is one of the puffiest planets known: If it could somehow be placed in a tub of water, it would float. The planet was also found to whip around its star in just less than five days.