Nedelin disaster

October 24, 1960

Cold war hysteria led to the rushed test-launch of an R-16 intercontinental ballistic missile at the Soviet Union’s Baikonur Cosmodrome that killed at least 92 people. With the R-16’s fuel tanks filled — and leaking — and worsening electrical problems, Marshal of Artillery Mitrofan Nedelin, reportedly under pressure from the Kremlin, ordered launch preparations to continue over workers’ objections. The rocket’s second stage ignited accidentally and mushroomed into a fireball 130 yards across that left deadly toxic chemicals in its wake. Exactly three years later, another accident at Baikonur claimed eight lives.

July 21, 1961

Splashdown came not with relief but terror for Mercury astronaut Gus Grissom after his 15 minutes in space. The hatch on his Liberty Bell 7 capsule came off and the craft began to fill with water. Marine divers rescued Grissom, who denied claims that he might have pulled the hatch in panic, but helicopters had to cut loose the sodden capsule. In 1999, the Discovery Channel funded a search and recovery operation for the craft, which was dredged up from a depth of 15,000 feet.

July 22, 1962

Mariner 1 was only about five minutes into its trip from Earth to Venus when a missing hyphen in its computer program caused it to veer dangerously off course, threatening to crash into heavily trafficked shipping lanes or a populated area. The range safety officer sent it a command to self-destruct just six seconds before the craft separated from its launch vehicle, which did not have a destruct mechanism. Its twin, Mariner 2, was deployed successfully the following month and took infrared measurements of Venus’s cool clouds and hot surface.

March 16, 1966

Gemini VIII astronauts David Scott and Neil Armstrong somehow kept level heads when their craft began to spin out of control half an hour after it docked with another vehicle, Agena — the first time two separately launched craft linked together in space. Hoping to stop the rolling and tumbling, the astronauts undocked, only to find their ship spun faster — once each second. Ten minutes later, balance was restored by firing the thrusters, one of which ironically had caused the problem when it became stuck in the “on” position.

January 27, 1967

Apollo 1 astronauts Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee were conducting a practice run for their launch the next month when an electrical short sparked a fire in the command module’s pure-oxygen environment. In the weightlessness of space, the fire’s own combustion products would have surrounded it and snuffed it out, but on Earth, the blaze engulfed the module and within 24 seconds, all three were dead. On each future mission, NASA installed an emergency escape hatch (it would have taken 90 seconds for the Apollo 1 team to break out to safety) and a system to dilute the oxygen for ground tests.

April 24, 1967

Vladimir Komarov became the first man to die in spaceflight when his problem-plagued Soyuz 1 craft crashed on return to Earth. Four previous unmanned flights of the Soyuz design had each malfunctioned in different ways, and mission designers had not wanted to send a cosmonaut up in it. But up Komarov went, and once in orbit, nothing seemed to work — one of two solar panels failed to deploy and the ship wouldn’t stabilize. On his 18th orbit around the planet, Komarov was able to manually fire the motor for re-entry, only to die when the craft’s primary parachute failed to open and the backup became tangled.

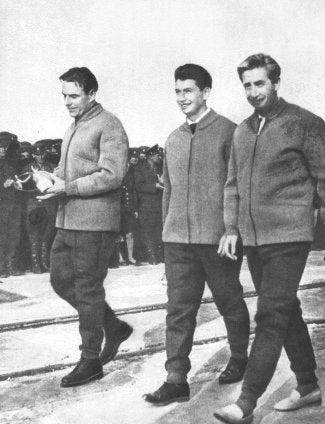

Komarov (left) is pictured here with his Voskhod crewmates Boris Yegorov (center) and Konstaning Feoktistov on October 12, 1964.

January 18, 1969

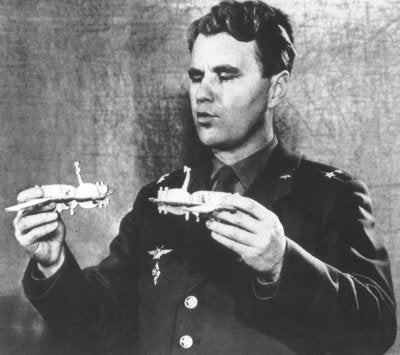

Soyuz 5 had successfully docked with sister ship Soyuz 4 (illustrated here by Soyuz 4 commander Vladimir Shatalov) in the first crew transfer between two vehicles in space when problems developed for cosmonaut Boris Volynov on re-entry. Unable to jettison the Equipment Module that was blocking the craft’s heat shield, Soyuz 5 somersaulted until it steadied itself with its thin-skinned nose pointing forward. Volynov frantically scribbled notes as smoke filled his cabin and he waited to die, but miraculously, the stresses of re-entry tore off the extra module and Soyuz 5 flipped into the right position. Despite impaired parachute function, Volynov survived a crash landing 1,200 miles from his target and was found hours later being tended to by villagers.

July 20, 1969

Even when it puts its best foot forward, the space program sometimes stumbles a little. When U.S. astronaut Neil Armstrong, the first man to walk on the moon, recited the line he had prepared for the momentous occasion, “That’s one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind,” he forgot to say the word “a.” And when his compatriot Buzz Aldrin put his foot down on the lunar surface, he felt the urine bag in his boot break.

November 20, 1969

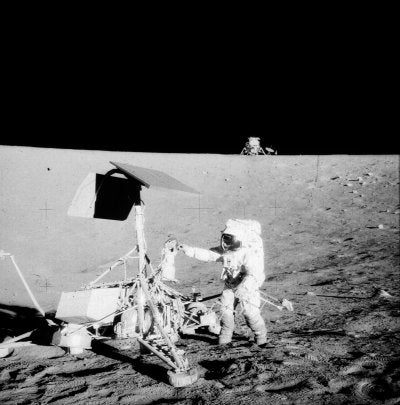

Less than a minute after launch, Apollo 12 was struck by lightning not once but twice. Circuit breakers tripped, and crewmembers Charles Conrad, Richard Gordon, and Alan Bean scrambled to reset the power buses before reaching orbit. They made it to the moon and on their second moonwalk, Bean and Conrad carried off pieces of the Surveyor 3 probe (shown at right with Conrad) that had landed two years before. Tests showed a bacterium on Surveyor 3’s removed parts — a sign of possible life on the moon — but soon scientists realized the germ was Earth-born and the probe hadn’t been properly sterilized.

April 13, 1970

Apollo 13, launched April 11 with a last-minute crew change because of rubella exposure, suffered an oxygen tank explosion on April 13 that nearly cost astronauts Jim Lovell, Jack Swigert, and Fred Haise their lives. Access to two fuel cells was lost and the only other oxygen tank began to leak, starving the remaining fuel cell. Giving up on a moon landing, the crew turned everything off except the communications and environmental controls systems and moved into the lunar module for 86 hours, straining its intended capacity of two people for 48 hours. Even the air crew members exhaled threatened to poison them in this cramped space, and mission controllers on the ground instructed the crew to make a carbon dioxide filter from materials on hand, just one of the measures that saved the astronauts’ lives.

June 29, 1971

Soyuz 11 cosmonauts Georgi Dobrovolsky, Vladimir Volkov, and Viktor Patsayev had just completed a record-breaking 23 days in space, most of which was spent as the first crew to board the world’s first orbiting space station, Salyut 1, when tragedy struck. A pressure relief valve was blown open when the three modules in the Soyuz 11 separated, as planned, for re-entry. The air in their descent module was sucked into space and the cosmonauts, who were not wearing pressurized suits, could not be revived when the module landed. The disaster prompted engineers to lower subsequent Soyuz crew sizes from three to two to accommodate the bulky, lifesaving suits.

January 28, 1986

The Challenger was seared into the memories of millions of people who watched in horror as it exploded shortly after launch on a cold January morning. Six astronauts and high-school teacher Christa McAuliffe died when their cabin plunged into the Atlantic. Two years of investigations determined the cause was faulty O-rings, plastic washers sandwiched between joints in the booster rockets. The cold weather made the usually flexible rings stiff, and hot gases escaped, which helped ignite the explosion.

1990 to 1993

After its deployment from Space Shuttle Discovery, the Hubble Space Telescope suffered from blurry vision due to a misshape in its primary mirror corresponding to 1/50 the thickness of a human hair. In December 1993 the first space shuttle servicing mission installed the Corrective Optics Space Telescope Axial Replacement (COSTAR) apparatus to sharpen Hubble’s gaze. Instruments added to the telescope later were built to correct for the misshapen mirror, so COSTAR will be removed during the fourth servicing mission (tentatively scheduled for late 2004).

February 23, 1997

The Russian Space Station Mir launched in 1986, endured a string of worrisome accidents, including both a fire and a collision with a cargo craft carrying garbage in 1997. The fire started when an oxygen-generating tool malfunctioned and burned for 90 seconds, damaging surrounding hardware. The crew, including U.S. astronaut and physician Jerry Linenger, used masks to breathe through the heavy smoke until the air was deemed safe. The failing Mir was purposely crashed into the Pacific Ocean in 2001.

February 1, 2003

The Space Shuttle Columbia was just 16 minutes from landing when it broke apart after nearly 15 days in space, killing all seven of its crew members and scattering debris across eastern Texas and western Louisiana. The international team of STS-107 enjoyed exceptional camaraderie, as evidenced by photographs such as this one, taken January 27. Clockwise from lower right are David Brown, Michael Anderson, Kalpana Chawla, and Ilan Ramon. Not pictured are Rick Husband, William McCool, and Laurel Clark.