Planet hunters using Keck Observatory have detected an extrasolar planet that is only 4 times the mass of Earth. The planet is the second smallest exoplanet ever discovered and adds to astronomers’ growing cadre of low-mass planets called super-Earths.

“This is quite a remarkable discovery,” said astronomer Andrew Howard of the University of California at Berkeley. “It shows that we can push down and find smaller and smaller planets.”

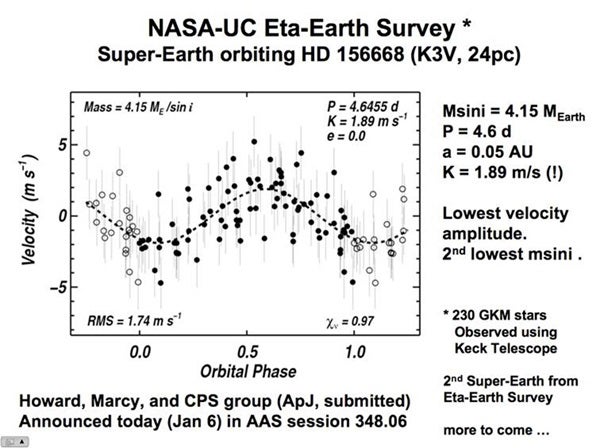

Dubbed HD156668b, the planet orbits its parent star in just over 4 days and is located roughly 80 light-years from Earth in the direction of the constellation Hercules. Howard, along with Geoff Marcy of the University of California at Berkeley, Debra Fischer of Yale University, John Johnson of the California of Institute of Technology, and Jason Wright of Penn State University, discovered the new planet with the 10-meter Keck I telescope atop Mauna Kea in Hawaii.

The researchers used the radial velocity or wobble method that relies on Keck’s High Resolution Echelle Spectrograph (HIRES) to spread light collected from the telescope into its component wavelengths, or colors. The result is called a spectrum. When the planet orbits around the back of the parent star, its gravity pulls slightly on the star, which causes the star’s spectrum to shift toward redder wavelengths. When the planet orbits in front of the star, it pulls the star in the other direction. The star’s spectrum shifts toward bluer wavelengths.

The color shifts give astronomers the mass of the planet and the characteristics of its orbit, such as the time it takes to orbit the star. Nearly 400 planets around other stars were discovered using this technique, but the majority of these planets are Jupiter-sized or larger.

“It’s been astronomers’ long-standing goal to find low-mass planets, but they are really hard to detect,” Howard said. He added that the new discovery has implications for not only exoplanet research, but also for solving the puzzle of how planets and planetary systems form and evolve.

Astronomers have pieces of the formation and evolutionary puzzle from the discovery of hundreds of high-mass planets. But, “there are important pieces we don’t have yet,” Howard said. “We need to understand how low-mass planets, like super-Earths, form and migrate.”

The goal of the Eta-Earth Survey for Low Mass Planets was to find these super-Earths. So far the survey has discovered two near-Earth-mass planets with more on the way.