Astronomers survey the scale of the universe by first measuring the distances to close-by objects and then using them as standard candles to pin down distances farther and farther out into the cosmos. But this chain is only as accurate as its weakest link. Up to now, finding an accurate distance to the LMC, one of the nearest galaxies to the Milky Way, has proved elusive. As stars in this galaxy are used to fix the distance scale for more remote galaxies, it is crucially important.

But careful observations of a rare class of double stars have now allowed a team of astronomers to deduce a more precise value for the LMC distance — 163,000 light-years.

“I am very excited because astronomers have been trying for a hundred years to accurately measure the distance to the Large Magellanic Cloud, and it has proved to be extremely difficult,” said Wolfgang Gieren from the University of Concepción in Chile. “Now, we have solved this problem by demonstrably having a result accurate to 2%.”

The improvement in the measurement of the distance to the LMC also gives better distances for many Cepheid variable stars. These bright pulsating stars are used as standard candles to measure distances out to more remote galaxies and to determine the expansion rate of the universe. This, in turn, is the basis for surveying the universe out to the most distant galaxies that can be seen with current telescopes. So the more accurate distance to the LMC immediately reduces the inaccuracy in current measurements of cosmological distances.

The astronomers worked out the distance to the LMC by observing rare close pairs of stars known as eclipsing binaries. As these stars orbit each other, they pass in front of each other. When this happens, as seen from Earth, the total brightness drops, both when one star passes in front of the other and when it passes behind.

By carefully tracking these changes in brightness and measuring the stars’ orbital speeds, it is possible to work out how big the stars are, their masses, and other information about their orbits. When this is combined with careful measurements of the total brightness and colors of the stars, scientists can find remarkably accurate distances.

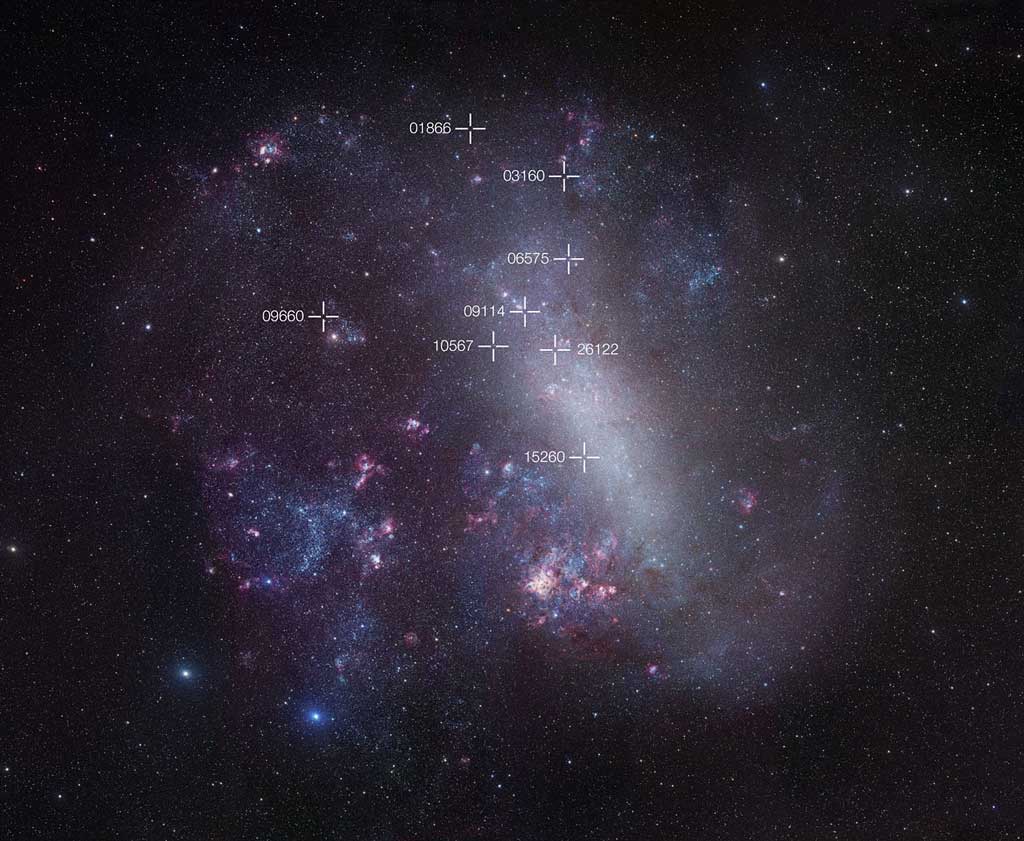

This method has been used before, but with hot stars; however, certain assumptions have to be made in this case, and such distances are not as accurate as scientists would like. But now, for the first time, scientists have identified eight extremely rare eclipsing binaries where both stars are cooler red giant stars. These stars have yielded more accurate distance values — accurate to about 2%.

“ESO provided the perfect suite of telescopes and instruments for the observations needed for this project — HARPS for extremely accurate radial velocities of relatively faint stars, and SOFI for precise measurements of how bright the stars appeared in the infrared,” said Grzegorz Pietrzynski from the University of Concepción in Chile and the Warsaw University Observatory in Poland.