The Event Horizon Telescope Array is almost certainly one of the most geographically widespread array telescopes ever “built”: spanning four continents, including Antarctica, the array taps into the potential of the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array along with around a dozen other telescopes.

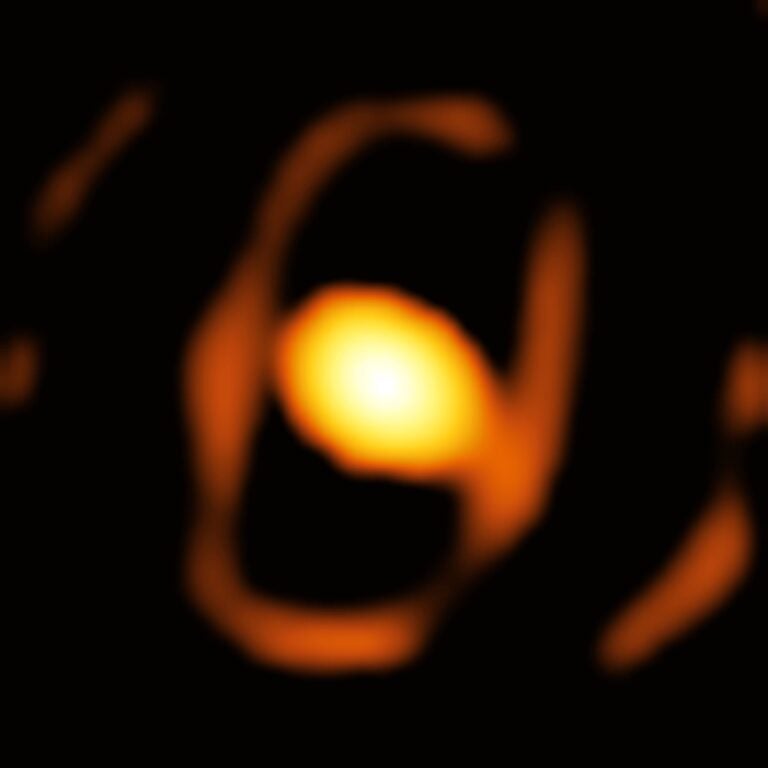

The goal? To image a black hole for the first time.

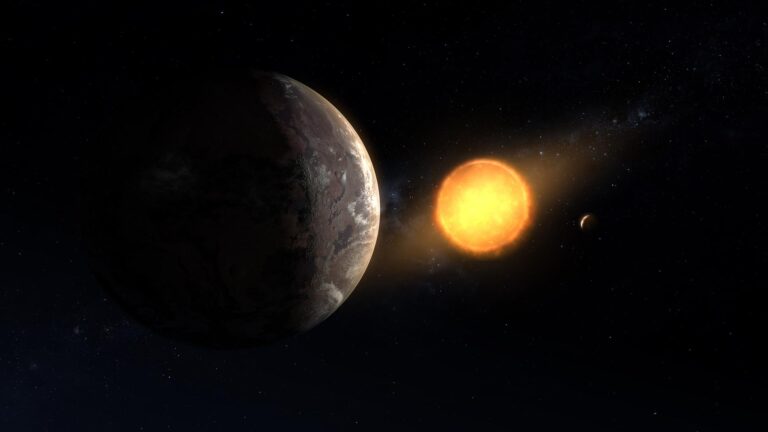

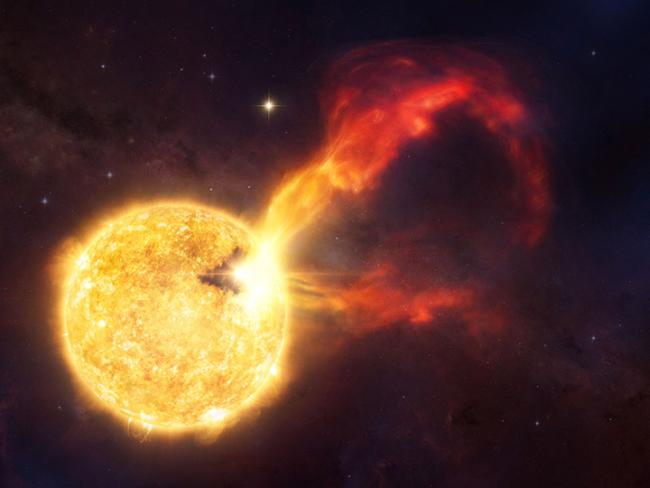

Scientists have discovered plenty of black holes, but the evidence has always been indirect. For instance, Cygnus X-1, the first discovered stellar mass black hole, gives away its presence by cannibalizing a nearby star and firing back hot jets of gas visible in X-ray, and many supermassive black holes are inferred either through gravitational influence or unlikely stars getting sucked into tidal disruption events. It’s sort of like watching a small ship sink without being able to see the whirlpool in the ocean taking it down.

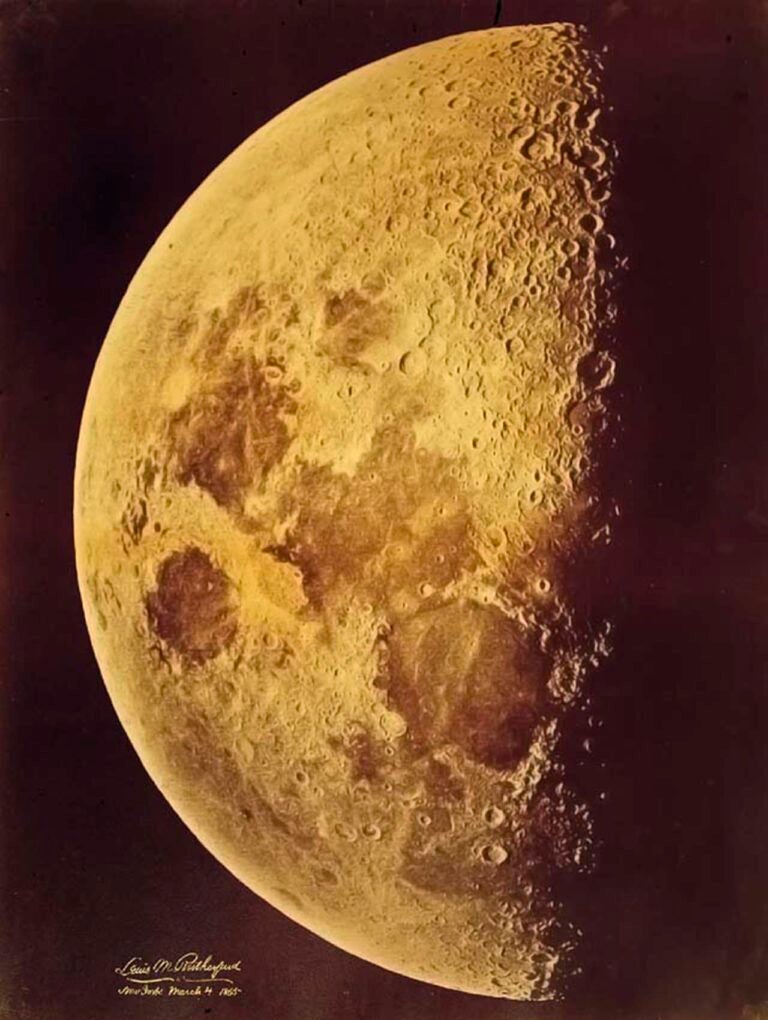

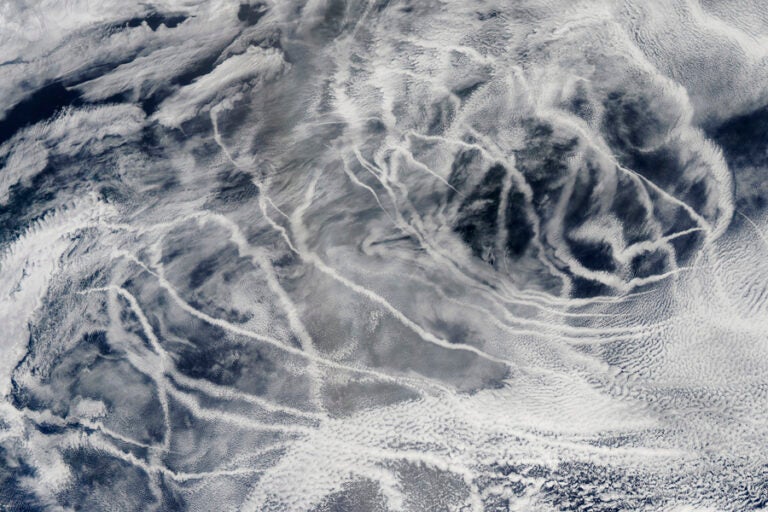

But by enlisting an array of telescopes, the Event Horizon Telescope will utilize very long baseline array interferometry to measure perturbations in gas around Sagittarius A (Sag A), the black hole at the center of our galaxy. In very long baseline array interferometry, the arrival of photons from Sag A will come at different times, with each telescope measuring the same event. By reconstructing what each telescope sees, a picture can emerge of whatever is happening at the center of our galaxy.

And then, for the first time, we’ll see inside a black hole instead of witnessing its effects, which will help astronomers answer questions about behaviors of these voracious beasts. While the campaign begins in April, the first finalized image may not come out until April.