Traveling at a mind-blowing 15,000 mph (24,100 km/h), the spacecraft will dip within 124 miles (200 kilometer) of Mercury and image much of the surface never before seen by spacecraft. As MESSENGER pulls away from the planet, it will view a region seen at high resolution only once before — when NASA’s Mariner 10 spacecraft made three flybys in 1974 and 1975, said Senior Research Associate William McClintock, a mission co-investigator from CU-Boulder’s Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP).

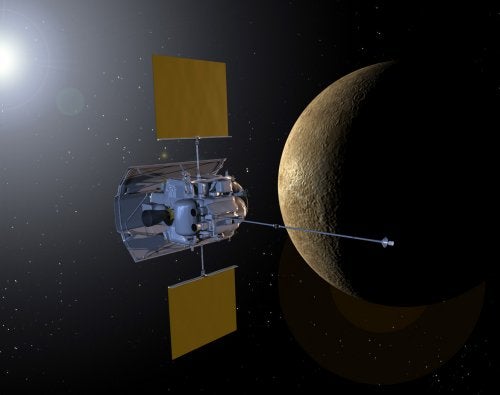

Launched in August 2004, MESSENGER will make the last of three passes by Mercury — the closest planet to the Sun — in October 2009 before finally settling into orbit around it in 2011. The circuitous, 4.9 billion-mile (7.9 billion km) journey to Mercury requires more than 6 years and 15 loops around the Sun to guide it closer to Mercury’s orbit. McClintock led the development of CU-Boulder’s Mercury Atmospheric and Surface Composition Spectrometer, or MASCS, miniaturized to weigh less than 7 pounds (3 kilograms) for the arduous journey.

The craft is equipped with a large Sunshade and heat-resistant ceramic fabric to protect it from the Sun, and more than half of the weight of the 1.2-ton spacecraft at launch consisted of propellant and helium. “We are almost two-thirds of the way there, but we still have a lot of work to do,” said McClintock. “We are continually refining our game plan, including developing contingencies for the unexpected.”

The desk-sized MESSENGER spacecraft is carrying seven instruments — a camera, a magnetometer, an altimeter, and four spectrometers (MASCS). Data from MASCS earlier this year during the first flyby January 14 provided LASP researchers with evidence that about 10 percent of the sodium atoms ejected from Mercury’s hot surface during the daytime were accelerated into a 25,000-mile-long (40,200 km) sodium tail trailing the planet, McClintock said.

MESSENGER will take data and images from Mercury for about 90 minutes October 6, when LASP will turn on a detector in MASCS for its first look at Mercury’s surface in the far ultraviolet portion of the light spectrum, said McClintock. The scanner will look at reflected light from Mercury’s surface to better determine the mineral composition of the planet.

“We got some surprising results with our UV detector in January, and we hope to see additional surprises as we extend our observations further into the ultraviolet,” he said.

The second Mercury flyby is slated for 5:40 a.m. EDT on October 6. LASP Director Daniel Baker, also a co-investigator on the MESSENGER mission, is using data from the mission to study Mercury’s magnetic field and its interaction with the solar wind. Mark Lankton is the LASP program manager for the MASCS instrument.