C assini scientists may have identified the source of one of Saturn’s more mysterious rings. Saturn’s G ring likely is produced by relatively large, icy particles that reside within a bright arc on the ring’s inner edge.

The particles are confined within the arc by gravitational effects from Saturn’s moon Mimas. Micrometeoroids collide with the particles, releasing smaller, dust-sized particles that brighten the arc. The plasma in the giant planet’s magnetic field sweeps through this arc continually, dragging out the fine particles, which create the G ring.

The finding is evidence of the complex interaction between Saturn’s moons, rings and magnetosphere. Studying this interaction is one of Cassini’s objectives.

“Distant pictures from the cameras tell us where the arc is and how it moves, while plasma and dust measurements taken near the G ring tell us how much material is there,” said Matthew Hedman, a Cassini imaging team associate at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York.

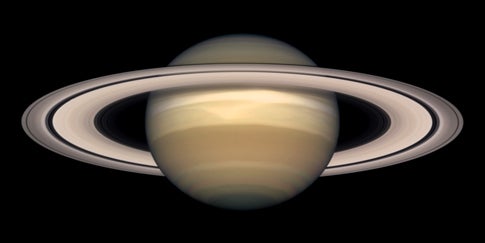

Saturn’s rings compose an enormous, complex structure and their origin is a mystery. The rings are labeled in the order they were discovered.

From the planet outward, they are D, C, B, A, F, G and E. Main rings A, B, and C, from edge-to-edge, would fit neatly in the distance between Earth and the Moon. The most transparent rings are D, F, E, and G, outside the main rings.

Unlike Saturn’s other dusty rings, the G ring is not associated closely with moons that either could supply material directly to it (as Enceladus does for the E ring), or sculpt and perturb its ring particles (as Prometheus and Pandora do for the F ring). Until now, the location of the G ring defied explanation.

As part of their study, Hedman and colleagues conducted computer simulations that showed the gravitational disturbance of Mimas could indeed produce such a structure in Saturn’s G ring. The only other places in the solar system where such disturbances occur are the ring arcs of Neptune.

Cassini’s magnetospheric imaging instrument detected depletions in charged particles near the arc in 2005. According to the scientists, unseen mass in the arc must be absorbing the particles. “The small dust grains that the Cassini camera sees are not enough to absorb energetic electrons,” said Elias Roussos of the Max-Planck-Institute for Solar System Research in Germany, and member of the magnetospheric imaging team. “This tells us that a lot more mass is distributed within the arc.”

The researchers concluded that there is a population of larger, as-yet-unseen bodies hiding in the arc, ranging in size from that of peas to small boulders. The total mass of all these bodies is equivalent to that of a 328-foot (100-meter) wide, ice-rich, small moon.

Joe Burns, member of the imaging team, said, “We’ll have a super opportunity to spot the G ring’s source bodies when Cassini flies about a thousand kilometers (600 miles) from the arc 18 months from now.”