Key Takeaways:

Scientists using NASA’s Cassini spacecraft at Saturn have stalked a new class of moons in the rings of Saturn that create distinctive propeller-shaped gaps in ring material. It marks the first time scientists have been able to track the orbits of individual objects in a debris disk. The research gives scientists an opportunity to time-travel back into the history of our solar system to reveal clues about disks around other stars in our universe that are too far away to observe directly.

“Observing the motions of these disk-embedded objects provides a rare opportunity to gauge how the planets grew from, and interacted with, the disk of material surrounding the early Sun,” said Carolyn Porco, from the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colorado. “It allows us a glimpse into how the solar system ended up looking the way it does.”

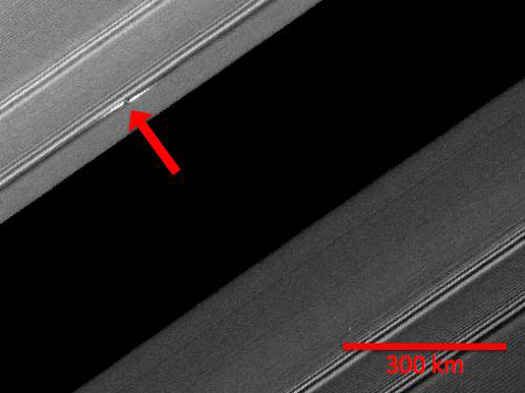

Cassini scientists first discovered double-armed propeller features in 2006 in an area now known as the “propeller belts” in the middle of Saturn’s outermost dense A ring. A new class of moonlets — smaller than known moons, but larger than the particles in the rings — that could clear the space immediately around them created the spaces. Those moonlets, which were estimated to number in the millions, were not large enough to clear out their entire path around Saturn, as do the moons Pan and Daphnis.

Matthew Tiscareno from Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, reports on a new cohort of larger and rarer moons in another part of the A ring farther out from Saturn. With propellers as much as hundreds of times as large as those previously described, these new objects have been tracked for as long as 4 years.

The propeller features are up to several thousand miles long and several miles wide. The moons embedded in the ring appear to kick up ring material as high as 1,600 feet (500 meters) above and below the ring plane, which is well beyond the typical ring thickness of about 30 feet (10 meters). Cassini is too far away to see the moons amid the swirling ring material around them, but scientists estimate that they are about 0.5 mile (1 kilometer) in diameter because of the size of the propellers.

Tiscareno and colleagues estimate there are dozens of giant propellers, and 11 of them were imaged multiple times between 2005 and 2009. One of them, nicknamed Bleriot after the famous aviator Louis Bleriot, showed up in more than 100 separate Cassini images and one ultraviolet imaging spectrograph observation over this time.

“Scientists have never tracked disk-embedded objects anywhere in the universe before now,” Tiscareno said. “All the moons and planets we knew about before orbit in empty space. In the propeller belts, we saw a swarm in one image and then had no idea later on if we were seeing the same individual objects. With this new discovery, we can now track disk-embedded moons individually over many years.”

Over the 4 years, the giant propellers have shifted their orbits, but scientists are not yet sure what is causing the disturbances in their travels around Saturn. Bumping into other smaller ring particles or responding to their gravity may upset their path, but the gravitational attraction of large moons outside the rings may also be a factor. Scientists will continue monitoring the moons to see if the disk itself is driving the changes, similar to the interactions that occur in young solar systems. If it is, Tiscareno said, this would be the first time such a measurement has been made directly.

“Propellers give us unexpected insight into the larger objects in the rings,” said Linda Spilker, from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “Over the next 7 years, Cassini will have the opportunity to watch the evolution of these objects and to figure out why their orbits are changing.”