Rosetta, which continues its scientific investigations at the comet until September before its own comet-landing finale, has in recent months been balancing science observations with flying dedicated trajectories optimized to listen out for Philae. But the lander has remained silent since July 9, 2015.

“The chances for Philae to contact our team at our lander control center are unfortunately getting close to zero,” said Stephan Ulamec from the German Aerospace Center, DLR. “We are not sending commands any more, and it would be very surprising if we were to receive a signal again.”

Philae’s team of expert engineers and scientists at the German, French, and Italian space centers and across Europe have carried out extensive investigations to try to understand the status of the lander, piecing together clues since it completed its first set of scientific activities after its historic landing on November 12, 2014.

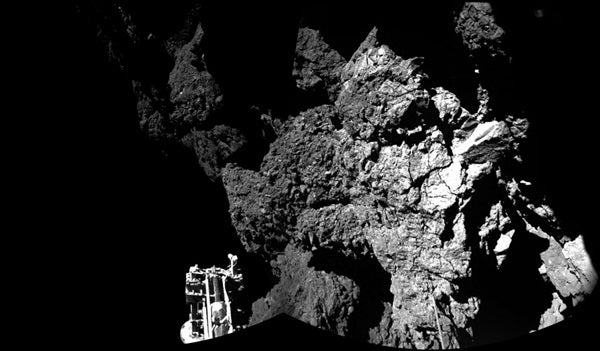

A story with incredible twists and turns unfolded on that day. In addition to a faulty thruster, Philae also failed to fire its harpoons and lock itself onto the surface of the comet after its seven-hour descent, bouncing from its initial touchdown point at Agilkia to a new landing site, Abydos, over 0.6 mile (1 kilometer) away. The precise location of the lander has yet to be confirmed in high-resolution images.

A reconstruction of the flight of the lander suggested that it made contact with the comet four times during its two-hour additional flight across the small comet lobe. After bouncing from Agilkia, it grazed the rim of the Hatmehit depression, bounced again, and then finally settled on the surface at Abydos.

Even after this unplanned excursion, the lander was still able to make an impressive array of science measurements, with some even as it was flying above the surface after the first bounce.

Once the lander had made its final touchdown, science and operations teams worked around the clock to adapt the experiments to make the most of the unanticipated situation. About 80 percent of its initial planned scientific activities were completed.

In the 64 hours following its separation from Rosetta, Philae took detailed images of the comet from above and on the surface, sniffed out organic compounds, and profiled the local environment and surface properties of the comet, providing revolutionary insights into this fascinating world.

But with insufficient sunlight falling on Philae’s new home to charge its secondary batteries, the race was on to collect and transmit the data to Rosetta and across 320 million miles (510 million kilometers) of space back to Earth before the lander’s primary battery was exhausted as expected. Thus, on the evening of November 14-15 2014, Philae fell into hibernation.

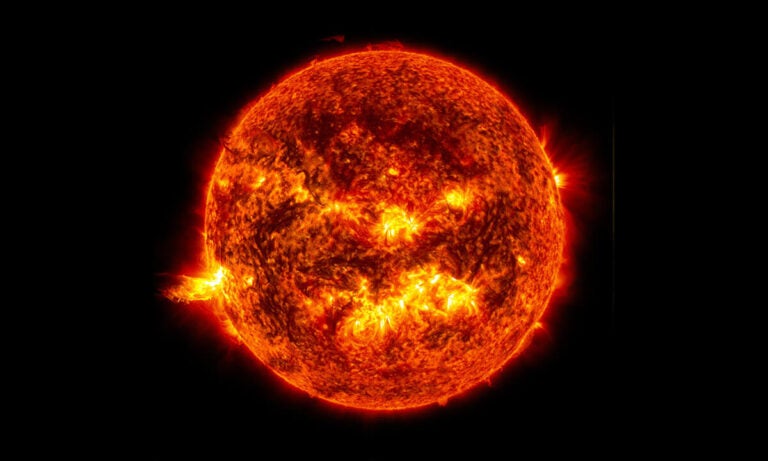

As the comet and the spacecraft moved closer to the Sun ahead of perihelion on August 13, 2015 — the closest point to the Sun along its orbit — there were hopes that Philae would wake up again.

Estimates of the thermal conditions at the landing site suggested that the lander might receive enough sunlight to start warming up to the minimum –45°C required for it to operate on the surface even by the end of March 2015.

It is worth noting that if Philae had remained at its original landing site of Agilkia, it would have likely overheated by March, ending any further operations.

On June 13, 2015, the lander finally hailed the orbiting Rosetta and subsequently transmitted housekeeping telemetry, including information from its thermal, power, and computer subsystems.

Subsequent analysis of the data indicated that the lander had in fact already woken up on April 26, 2015, but had been unable to send any signals until June 13.

The fact that the lander had survived the multiple impacts on November 12 and then unfavorable environmental conditions, greatly exceeding the specifications of its various electronic components, was quite remarkable.

After June 13, Philae made a further seven intermittent contacts with Rosetta in the following weeks, with the last coming on July 9. However, the communications links that were established were too short and unstable to enable any scientific measurements to be commanded.

Despite the improved thermal conditions, with temperatures inside Philae reaching 32°F (0°C), no further contacts were made as the comet approached perihelion in August.

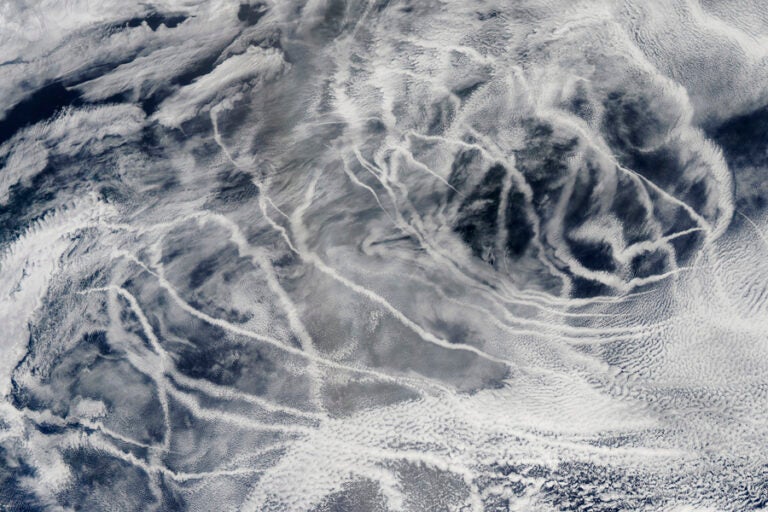

However, the months around perihelion are also the comet’s most active. With increased levels of outflowing gas and dust, conditions were too challenging for Rosetta to safely operate close enough to the comet and within the 124 miles (200 km) where the signals had previously been detected from Philae.

In more recent months, the comet’s activity has subsided enough to make it possible to approach the nucleus again safely — this week the spacecraft reached around 28 miles (45 km) — and Rosetta has made repeated passes over Abydos.

No signal has been received, however. Attempts to send commands “in the blind” to trigger a response from Philae have also not produced any results.

The mission engineers think that failures of Philae’s transmitters and receivers are the most likely explanation for the irregular contacts last year, followed by continued silence into this year.

Another difficulty that Philae may be facing is dust covering its solar panels, ejected by the comet during the active perihelion months, preventing the lander from powering up.

Also, the attitude and even location of Philae may have changed since November 2014 owing to cometary activity, meaning that the direction in which its antenna is sending signals to Rosetta is not as predicted, affecting the expected communication window.

“The comet’s level of activity is now decreasing, allowing Rosetta to safely and gradually reduce its distance to the comet again,” said Sylvain Lodiot from ESA.

“Eventually, we will be able to fly in ‘bound orbits’ again, approaching to within 6-12 miles (10-20 km) — and even closer in the final stages of the mission — putting us in a position to fly above Abydos close enough to obtain dedicated high-resolution images to finally locate Philae and understand its attitude and orientation.”

“Determining Philae’s location would also allow us to better understand the context of the incredible in situ measurements already collected, enabling us to extract even more valuable science from the data,” said Matt Taylor from ESA.

“Philae is the cherry on the cake of the Rosetta mission, and we are eager to see just where the cherry really is!”

At the same time, Rosetta, Philae, and the comet are heading back out towards the outer solar system again. They have crossed the orbit of Mars and are now some 220 million miles (350 million km) from the Sun. According to predictions, the temperatures should be falling far below those at which Philae is expected to be able to operate.

Nevertheless, while hopes of making contact again with Philae dwindle, Rosetta will continue to listen for signals from the lander as it flies alongside the comet ahead of its own comet landing in September.

“We would be very surprised to hear from Philae again after so long, but we will keep Rosetta’s listening channel on until it is no longer possible due to power constraints as we move ever further from the Sun towards the end of the mission,” said Patrick Martin from ESA.

“Philae has been a tremendous challenge, and for the lander teams to have achieved the science results that they have in the unexpected and difficult circumstances is something we can all be proud of.

“The combined achievements of Rosetta and Philae, rendezvousing with and landing on a comet, are historic high points in space exploration.”