Key Takeaways:

“In Lucania, it was alleged that the heavens had been on fire; at Privernum the Sun had been glowing red through the whole of a cloudless day; at the temple of Juno Sospita in Lanuvium a terrible noise was heard in the night.”

Not to mention children born of “uncertain sex,” or a lamb with a pig’s head in the town of Frusino.

In March, Andrew Solow of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts published the most detailed analysis of Roman sky signs so far. He built on similar work done in 1979 by Richard Stothers of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

The work of Roman historian Titus Livius (Livy, in English), who lived from 59 B.C. – A.D. 17, formed the basis of both studies. Livy’s Ab Urbe Condita, written in the time of the first emperors, chronicles Rome’s history with the help of written records dating back hundreds of years. Many times, he reports how Romans interpreted natural events as warnings that something was amiss in the relationship between the state and its gods.

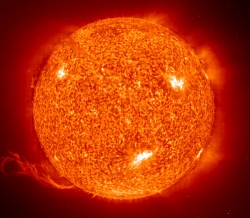

When Stothers embarked on his project 30 years ago, he thought Livy had done the most consistent job for the 133-year period from 223 B.C. to 91 B.C. He showed these events increased and decreased with a period of about 11 years. That’s the average activity cycle for the Sun, and Stothers concluded most of the heavenly portents Romans worried about were aurorae — atmospheric glows triggered when solar storms sweep past Earth.

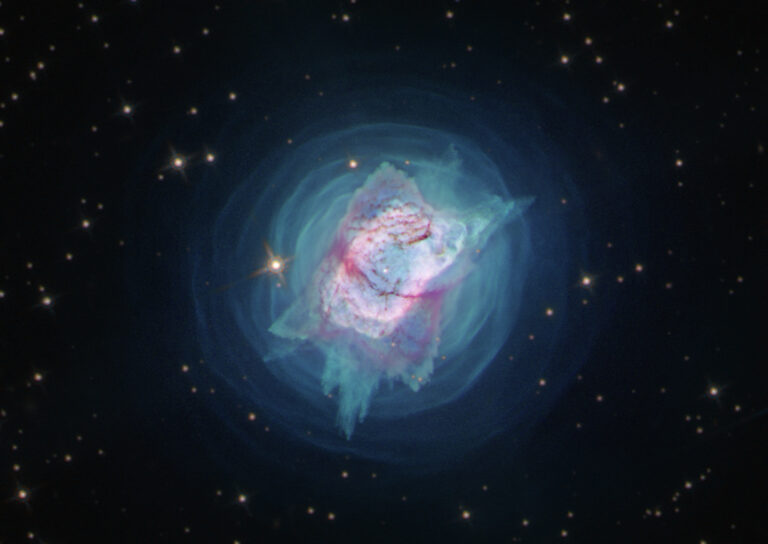

With descriptions such as “the sky lit up during the night,” “the sky appeared to be on fire,” or even “a phantom navy was seen shining in the sky,” one can well imagine Livy’s sources are reporting aurorae.

Solow’s work, which appeared in the March 30, 2005, issue of Earth and Planetary Science Letters, shows these events happen most often 4 years and 8 years into the 11-year cycle. This twin-peaked, or bimodal, distribution matches that seen in the modern aurora record.

“My 1979 analysis … found the 11-year solar cycle, but completely overlooked the possibility that the frequency distribution of aurorae might be bimodal, as it has been in modern times,” Stothers told Astronomy. “Solow has demonstrated bimodality in the ancient data amazingly well.”

Ancient records interest solar scientists because they give us a glimpse of past solar behavior. Modern records go back only to about 1750, when astronomers began counting sunspots systematically. Two millennia ago, as now, the Sun displayed an 11-year cycle. Now, Solow’s work shows that, whatever its origin, bimodality also has been part of the solar cycle during the past 2,000 years.

Sometimes, though, other phenomena must have triggered Roman anxiety. A “fiery torch” in the sky may also describe a comet, for example. That’s one of the things Solow has been thinking about. Nowadays, in Italy, he says, you can expect aurorae about once every 10 years. In Livy’s history of Rome, celestial portents are reported about every four years. He argues there’s probably a background noise of comets and meteors in Livy’s work, topped with the periodic signal from aurorae.