Key Takeaways:

“These jets arise as infalling matter approaches the black hole, but we don’t yet know the details of how they form and maintain themselves,” said Cornelia Mueller from the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, Germany.

The new image shows a region less than 4.2 light-years across — less than the distance between our Sun and the nearest star. Radio-emitting features as small as 15 light-days can be seen, making this the highest-resolution view of galactic jets ever made.

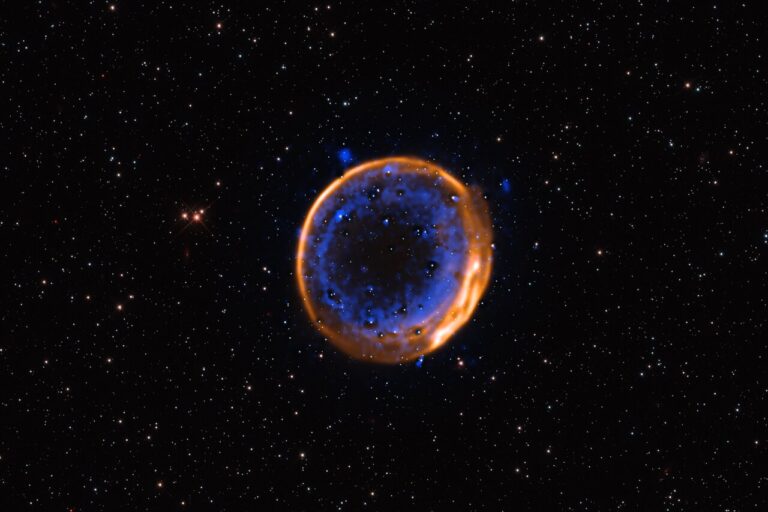

Mueller and her team targeted Centaurus A (Cen A), a nearby galaxy with a supermassive black hole weighing 55 million times the Sun’s mass. Also known as NGC 5128, Cen A is located about 12 million light-years away in the constellation Centaurus and is one of the first celestial radio sources identified with a galaxy.

When seen in radio waves, Cen A is one of the biggest and brightest objects in the sky, nearly 20 times the apparent size of a Full Moon. This is because the visible galaxy lies nestled between a pair of giant radio-emitting lobes, each nearly a million light-years long.

These lobes are filled with matter streaming from particle jets near the galaxy’s central black hole. Astronomers estimate that matter near the base of these jets races outward at about one-third the speed of light.

Using an intercontinental array of nine radio telescopes, researchers for the Tracking Active Galactic Nuclei with Austral Milliarcsecond Interferometry (TANAMI) project were able to effectively zoom into the galaxy’s innermost realm.

“Advanced computer techniques allow us to combine data from the individual telescopes to yield images with the sharpness of a single giant telescope — one nearly as large as Earth itself,” said Roopesh Ojha from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

The enormous energy output of galaxies like Cen A comes from gas falling toward a black hole possessing millions of times the Sun’s mass. Through processes not fully understood, some of this infalling matter is ejected in opposing jets at a substantial fraction of the speed of light. Detailed views of the jet’s structure will help astronomers determine how they form.

The jets strongly interact with surrounding gas, at times possibly changing a galaxy’s rate of star formation. Jets play an important but poorly understood role in the formation and evolution of galaxies. NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope has detected much higher-energy radiation from Cen A’s central region.

“This radiation is billions of times more energetic than the radio waves we detect, and exactly where it originates remains a mystery,” said Matthias Kadler from the University of Wuerzburg, Germany, and a collaborator of Ojha. “With TANAMI, we hope to probe the galaxy’s innermost depths to find out.”

“These jets arise as infalling matter approaches the black hole, but we don’t yet know the details of how they form and maintain themselves,” said Cornelia Mueller from the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, Germany.

The new image shows a region less than 4.2 light-years across — less than the distance between our Sun and the nearest star. Radio-emitting features as small as 15 light-days can be seen, making this the highest-resolution view of galactic jets ever made.

Mueller and her team targeted Centaurus A (Cen A), a nearby galaxy with a supermassive black hole weighing 55 million times the Sun’s mass. Also known as NGC 5128, Cen A is located about 12 million light-years away in the constellation Centaurus and is one of the first celestial radio sources identified with a galaxy.

When seen in radio waves, Cen A is one of the biggest and brightest objects in the sky, nearly 20 times the apparent size of a Full Moon. This is because the visible galaxy lies nestled between a pair of giant radio-emitting lobes, each nearly a million light-years long.

These lobes are filled with matter streaming from particle jets near the galaxy’s central black hole. Astronomers estimate that matter near the base of these jets races outward at about one-third the speed of light.

Using an intercontinental array of nine radio telescopes, researchers for the Tracking Active Galactic Nuclei with Austral Milliarcsecond Interferometry (TANAMI) project were able to effectively zoom into the galaxy’s innermost realm.

“Advanced computer techniques allow us to combine data from the individual telescopes to yield images with the sharpness of a single giant telescope — one nearly as large as Earth itself,” said Roopesh Ojha from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

The enormous energy output of galaxies like Cen A comes from gas falling toward a black hole possessing millions of times the Sun’s mass. Through processes not fully understood, some of this infalling matter is ejected in opposing jets at a substantial fraction of the speed of light. Detailed views of the jet’s structure will help astronomers determine how they form.

The jets strongly interact with surrounding gas, at times possibly changing a galaxy’s rate of star formation. Jets play an important but poorly understood role in the formation and evolution of galaxies. NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope has detected much higher-energy radiation from Cen A’s central region.

“This radiation is billions of times more energetic than the radio waves we detect, and exactly where it originates remains a mystery,” said Matthias Kadler from the University of Wuerzburg, Germany, and a collaborator of Ojha. “With TANAMI, we hope to probe the galaxy’s innermost depths to find out.”