Human beings always seem drawn to vacant spaces. In Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein, published in 1818, one pole-bound character captures this appeal when he says, “I shall satiate my ardent curiosity with the sight of a part of the world never before visited, and may tread a land never before imprinted with the foot of man.” Many real-life contemporaries would have joined him, compelled by the same urge.

Sir John Franklin’s 1845 expedition was the largest of numerous polar explorations sent out by Britain and other countries. Why Britain and not the United States? At the time, Britain had the world’s largest and most powerful navy, which contained a glut of able and ambitious naval officers. These men saw their careers in danger of falling onto a lee shore in the post-Waterloo peace — so what better way to stand out than through arduous and dangerous exploration? In addition, Britain’s global commerce gave economic impetus to scouting new routes to old places — hence the search for the Northwest Passage.

When we look at British polar expeditions in the early and mid-19th century, it’s striking they were not manned by the conscripts and press-gang sweepings who, despite all odds, smashed the French and Spanish navies at Trafalgar a generation before. Instead, by the standards of the age, the polar crews were men well-fed (at least initially) and intelligent. More important, they were volunteers.

Most remarkable, of those who went with Franklin, many had returned to the polar world repeatedly, despite bad experiences and the well-documented hardships of earlier expeditions. These men were drawn irresistibly poleward like human compass needles.

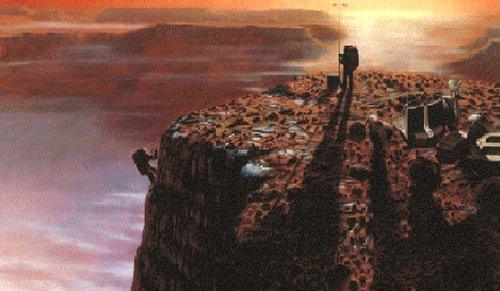

It’s not hard to see parallels to today’s astronaut crews — even the emptiness of the polar regions echoes that of space, and both realms provide a sense of being utterly alone amid vast emptiness. In both cases, also, the adventurers have the benefits of the most advanced technology of their day.

Once the path to adventure lay in steering a ship’s course into the wintry world found in high latitudes. Now we see another, more literal, vacuum drawing those imbued with a spirit of adventure. Tomorrow’s spacefaring crews that travel into the unknown will go better prepared than Franklin and his men did. The food, at least, won’t be deadly, however uninspiring it may be. And the terrors, which surely await, will be better anticipated.

Yet spacefaring will never be free of danger. Solar flares can kill or maim explorers today just as unrelenting cold, vitamin deficiency, and starvation did 160 years ago.

Adventuring into the truly unknown at the risk of one’s life isn’t for everyone. But all of us are enriched by the wonders such explorers find.