Scientists using a continent-wide array of radio telescopes have made an extremely precise measurement of the curvature of space caused by the Sun’s gravity. Their technique promises a major contribution to a frontier area of basic physics.

“Measuring the curvature of space caused by gravity is one of the most sensitive ways to learn how Einstein’s theory of general relativity relates to quantum physics,” said Sergei Kopeikin of the University of Missouri. “Uniting gravity theory with quantum theory is a major goal of 21st-century physics, and these astronomical measurements are a key to understanding the relationship between the two.”

Kopeikin and his colleagues used the National Science Foundation’s Very Long Baseline Array (VLBA) radio-telescope system to measure the bending of light caused by the Sun’s gravity to within one part in 30,000. With further observations, the scientists say their precision technique can make the most accurate measure ever of this phenomenon.

Bending of starlight by gravity was predicted by Albert Einstein when he published his general theory of relativity in 1916. According to relativity theory, the strong gravity of a massive object such as the Sun produces curvature in the nearby space, which alters the path of light or radio waves passing near the object. The phenomenon was first observed during a solar eclipse in 1919.

Although numerous measurements of the effect have been made over the intervening 90 years, the problem of merging general relativity and quantum theory has required ever more accurate observations. Physicists describe the space curvature and gravitational light-bending as a parameter called “gamma.” Einstein’s theory holds that gamma should equal exactly 1.0.

“Even a value that differs by one part in a million from 1.0 would have major ramifications for the goal of uniting gravity theory and quantum theory, and thus in predicting the phenomena in high-gravity regions near black holes,” Kopeikin said.

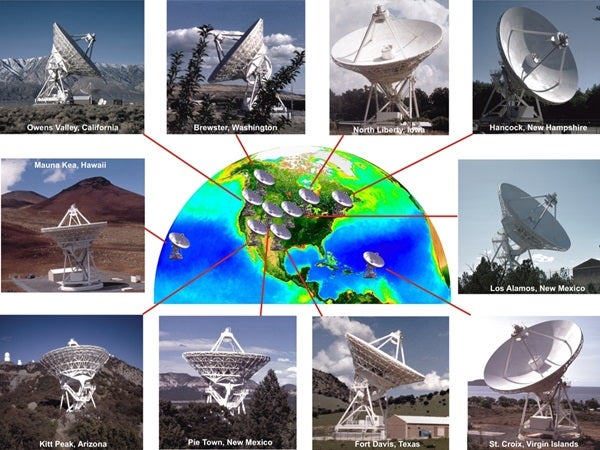

To make extremely precise measurements, the scientists turned to the VLBA, a continent-wide system of radio telescopes ranging from Hawaii to the Virgin Islands. The VLBA offers the power to make the most accurate position measurements in the sky and the most detailed images of any astronomical instrument available.

The researchers made their observations as the Sun passed nearly in front of four distant quasars — faraway galaxies with supermassive black holes at their cores — in October 2005. The Sun’s gravity caused slight changes in the apparent positions of the quasars because it deflected the radio waves coming from the more-distant objects.

The result was a measured value of gamma of 0.9998 ± 0.0003, in excellent agreement with Einstein’s prediction of 1.0.

“With more observations like ours, in addition to complementary measurements such as those made with NASA’s Cassini spacecraft, we can improve the accuracy of this measurement by at least a factor of four, to provide the best measurement ever of gamma,” said Edward Fomalont of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO). “Since gamma is a fundamental parameter of gravitational theories, its measurement using different observational methods is crucial to obtain a value that is supported by the physics community.”

Kopeikin and Fomalont worked with John Benson of the NRAO and Gabor Lanyi of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. They reported their findings in the July 10 issue of the Astrophysical Journal.