We’ll start with Mercury, which makes a brief appearance after sunset. It reaches greatest eastern elongation October 1, standing 26° east of the Sun. Mercury lies well south of the ecliptic plane, which makes a shallow angle with the western horizon, so the innermost planet remains low. Begin looking 30 minutes after sunset to spot the magnitude 0 planet 3° high in the west-southwest. It sets 20 minutes later, so you don’t have long.

Mercury gets fainter each morning and is magnitude 0.1 October 8. It lingers only 2° high 30 minutes after sunset and sets 15 minutes later, heading toward an October 25th inferior conjunction with the Sun. It will reappear in the morning sky early next month.

Jupiter stands 30° high in the southern sky an hour after sunset at the beginning of the month, and is well positioned for a few hours of observing before it descends in the west. Glowing at magnitude –2.4, it’s the brightest object in the sky except for the Moon. It dips to –2.2 by month’s end. Jupiter sets after midnight on October 1 and is gone by 11 P.M. local time on October 21.

Joining Jupiter in your telescope are the four Galilean moons, Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. Before the planet descends too low, there’s a short window to see some of its regularly occurring satellite events, such as transits, occultations, and shadow transits. You can find out about upcoming events each week at www.astronomy.com/observing/sky-this-week.

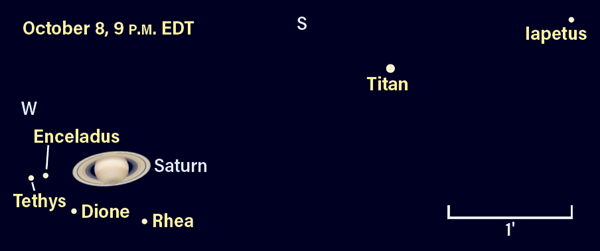

Saturn stands 7° east of Jupiter, also in Sagittarius, on October 1. The gap narrows to 5° by October 31. A waxing First Quarter Moon stands south of the planetary duo on October 22. Saturn shines at magnitude 0.5 and, by the end of October, sets by 11 P.M. local time.

Saturn is always a crowd-pleaser through a telescope. Its majestic ring system is on view, spanning 38″ compared with the 17″-wide disk. If seeing conditions are good, look for the dark Cassini Division and the shadow of the disk projected onto the far side of the rings.

Saturn’s brightest moon, Titan, shines at 8th magnitude, while a trio of 10th-magnitude moons — Tethys, Dione, and Rhea — skitter closer to the rings. Look carefully at the edge of the rings to spy Enceladus, a 12th-magnitude firefly hidden in Saturn’s searchlight glow. Iapetus brightens as it moves west of Saturn following conjunction, heading toward western elongation early next month. The brighter of the moon’s two hemispheres is turning toward Earth in the latter half of October.

Neptune shines all month at magnitude 7.8. During October, the ice giant moves westward from a point 1.6° east-northeast of Phi Aquarii to 57′ from the star. A telescope will reveal the planet’s bluish disk, spanning 2″.

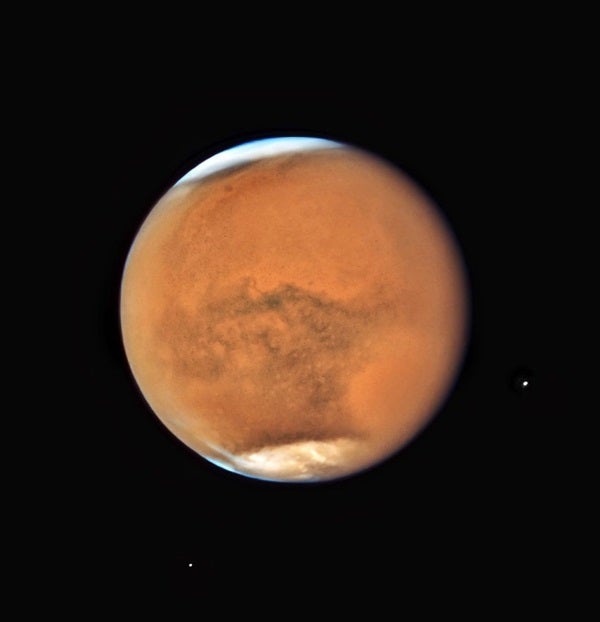

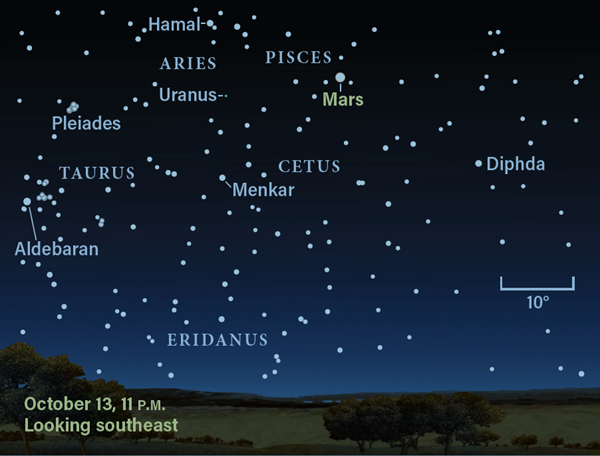

A Full Moon rises with Mars on October 1. An hour after sunset, Mars stands 13.5° east of our satellite and shines brilliantly at magnitude –2.5. Located in Pisces, Mars rises by 8 P.M. local time and is at its best apparition in years for Northern Hemisphere observers. It reaches its long-awaited opposition on October 13 and moves westward along its retrograde path, reaching a point 3° south of Epsilon (ε) Piscium on October 31. It won’t appear better than this until 2035.

The Red Planet is closest to Earth on October 6, when it sits 0.41 astronomical unit (38.1 million miles [61.3 million kilometers], where 1 AU is the average Earth-Sun distance) from our planet and achieves magnitude –2.6.

Although Mars is not quite as close as the perihelic opposition of July 2018, it stands 30° higher in Northern Hemisphere skies. The higher altitude means light from Mars passes through our atmosphere along a shorter path than it did in 2018. Through a telescope, the planet’s 23″-wide disk presents a wealth of detail for the careful observer, and the best views of the Red Planet are when it stands highest in the sky during the couple of hours around local midnight.

Mars rotates in 24 hours 36 minutes (14° per hour), so when observing at the same time each evening, the planet appears to have rotated backward compared to the previous day. In early October, the Hellas Basin and Syrtis Major are rotating off the fully illuminated disk at 12 A.M. EDT. At that time, eastern observers will see that Syrtis Major has not quite reached the limb, but observers in western states will see the feature has almost gone. Syrtis Major is positioned near the center of the disk from October 5 through 9 at 12 A.M. EDT. Again, West Coast observers should look earlier. To its south is the bright Hellas Basin, often the source of localized dust storms. Observers are hoping this year that dust storms won’t affect the entire planet, as they did in 2018.

The Full Moon shares the sky with Mars for the second time this month on the 29th. You’ll find the planet less than 5° northwest of the Moon an hour after sunset.

Uranus reaches opposition on the 31st in a sparse region of the sky in southern Aries. A bright gibbous Moon rises nearby on October 3, and by 2 A.M. EDT on October 4, the planet is 4.3° north of our satellite, appearing as a magnitude 5.7 starlike object.

When the Moon is gone, the best way to catch the planet is to scan with binoculars between Hamal, the brightest star in Aries, and Menkar (Alpha [α] Ceti). Uranus lies 10.5° from Hamal along this line. There are no bright stars nearby; the closest is 6th-magnitude 29 Arietis. Uranus lies 1.2° southwest of this star on October 1. The planet moves westward along its retrograde path and is 2.3° from the star by October 31. It’s the best time to spy the distant planet through a telescope, as it is visible all night. High magnification reveals a 4″-wide disk.

Venus rises around 4:00 A.M. local time on October 1, alongside Regulus in Leo. The pair stand 1.8° apart. Venus shines at a brilliant magnitude –4.1, 145 times brighter than Regulus at magnitude 1.3. At 5 A.M. EDT on October 2 and 3, you’ll find the planet 41″ and 30″ from the star, respectively.

Venus progresses across southern Leo during October, passing 2.7° south of the galaxy M95 on October 10. A crescent Moon joins the planet on the 14th. Venus crosses into Virgo on the 23rd, ending October within 1° of 4th-magnitude Zaniah (Eta [η] Virginis).Telescopic views show the planet changing from a 72 percent-lit disk on October 1 to 81-percent illuminated on October 31st, its diameter simultaneously diminishing from 16″ to 13″, owing to its increasing distance from Earth.

Rising Moon: Out on a limb

A 3D perspective is one of the big draws of solar system observing. Nowhere else is the effect greater than along the edge of our Moon.

We gain the strongest sense of depth from shadows cast by tall crater rims onto the floors below. At low Sun angles, the sharpness and length of shadows can so exaggerate the relief that early selenographers mistakenly thought the lunar terrain was quite jagged. However, if you check out the limb with high power, you’ll see the true profile is much smoother — bumpy, to be sure, but not saw-toothed.

Beginning on October 19th, the first thing to jump out at you will be the sunrise on the magnificent Mare Crisium, north of the lunar equator. After you gawk at its circle of peaks towering over a rolling sea of wrinkled ridges, tear yourself away and scan farther north along the rim of the three-day-old Moon. Look for a large flat zone with a dark swath: Mare Humboldtianum. Not quite at its cusp is the large crater Nansen, named for a Norwegian explorer of Earth’s polar region. Its broad, tall rim casts a wall of shadow onto its floor.

Over the next few evenings, you might notice how far Mare Crisium is from the limb. It’s as if the Moon is turning its face slightly to the side. Although Luna’s spin is constant, our satellite is currently on the slower-moving part of its elliptical orbit. The apparent rolling motion is called libration.

With the nights ticking toward Full phase, watch Mare Crisium continue to shift toward the limb. It’s easiest to see this with the unaided eye in daylight, when there is less glare. Binoculars also provide a great view. In a telescope, Humboldtianum slowly sprouts ears and a large divot as it turns back into profile.

The libration and phase cycles are both monthly, but not exactly — so they quickly fall out of sync. There’s always something different next time, with true repetitions occurring only after a Saros cycle of 18 years 10 days.

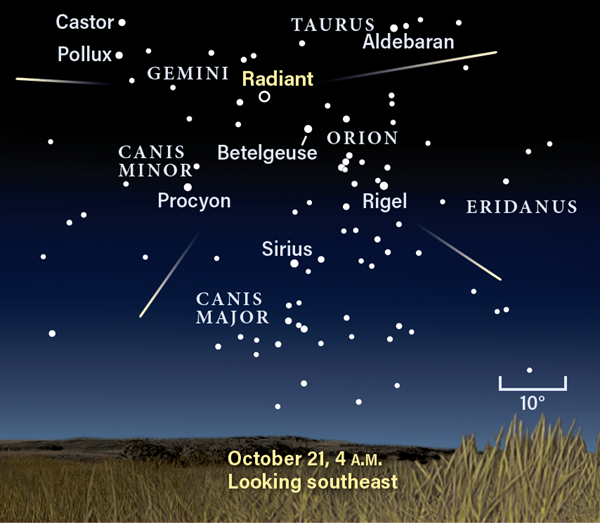

Meteor Watch: Hunt meteors in the Hunter

A very favorable appearance of the Orionid meteor shower occurs between October 2 and November 7. The shower peaks October 21, when the Moon is just 5 days old. On the night before maximum, the radiant in northern Orion rises shortly before midnight, just as the Moon sets. The radiant climbs higher in the sky through dawn. The listed zenithal hourly rate of 20 meteors per hour may occur in the hour before dawn. From a dark site with Orion lower in the sky, rates will also be lower.

The shower is the result of debris shed by Comet 1P/Halley and is a regular on the annual meteor shower calendar. With so much planetary action this month, keep a lookout for fast-paced Orionid meteors burning up in our atmosphere over a few nights centered on the peak.

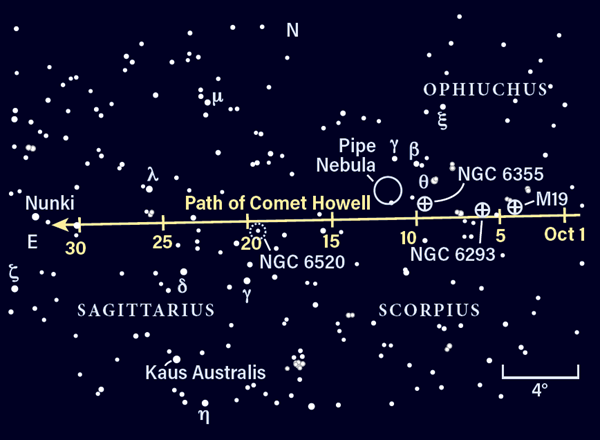

Comet Search: The Milky Way gets the green light

Sure to be a highlight of fall evenings, interplanetary visitor 88P/Howell is a must-see crossing the heart of our galaxy. Well within reach of a 4-inch scope under a dark sky, the soft gray light of ionized gases surrounding the comet’s head should glow a distinct green in larger instruments.

Early in the month, Howell and Sagittarius set in the southwest shortly after dusk. The dark-sky window before moonrise opens for one hour on October 5 and widens over the following nights. We quickly lose contrast on the 20th, thanks to a waxing crescent Moon.

Of particular interest is the 11th through the 13th, when Howell crosses the hindquarters of the Prancing Horse dust cloud. Visual observers will recognize this as the bowl of Barnard’s Pipe Nebula. You can trap this wild stallion and still get to bed by 11 P.M.

There are several other dates of note: On October 5, Howell is outshined by M19 nearby. On the 6th, the comet switches roles to rival NGC 6293; on the 9th and 10th, it slides past NGC 6355; and on the 19th, it shares the sky with NGC 6520. Compare and contrast their form and structure.

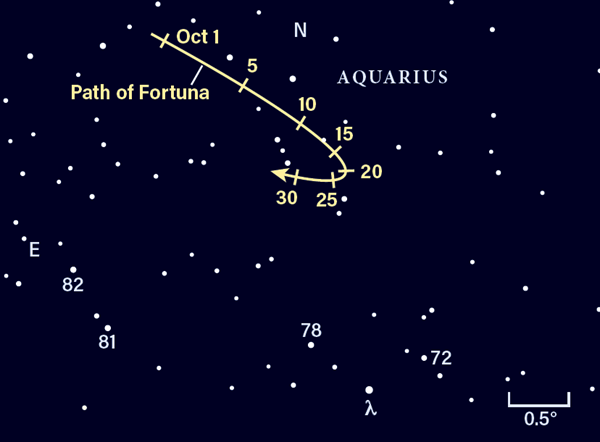

Locating Asteroids: Watery wanderings

The astronomical embodiment of Lady Luck highlights some passing coincidences in Aquarius. Named after the Roman goddess, 19 Fortuna is a 125-mile-wide boulder in the main asteroid belt. Find her by dropping down the right side of the Great Square of Pegasus until you meet Lambda (λ) Aquarii, shining modestly at magnitude 3.7, then nudge your scope north 1.5°, or three Moon-widths.

By chance, a different belt loops through this part of the sky: that of geostationary satellites. The chance is high to see some. First, create a framework sketch of five or six stars in the low-power field where Fortuna lies — one of them is probably our 10th-magnitude asteroid. Within 10 to 20 minutes, a satellite is likely to enter the eyepiece and take three to four minutes to slide across. Appearing no different than a background star, it may be as bright as 5th magnitude!

Once a satellite drifts into your field of view, turn off your drive and watch the sky flow past. In 25 minutes, bluish Neptune makes an appearance. Even if you can’t resolve its tiny disk, the ice giant will look like a “flat” magnitude 7.8 star.

Avoid the nights of October 25 through 27, when the glare of the nearby Moon interferes.