Key Takeaways:

“We got lucky to have captured an outburst from the black hole during our observing campaign,” said Fiona Harrison from the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. “These data will help us better understand the gentle giant at the heart of our galaxy and why it sometimes flares up for a few hours and then returns to slumber.”

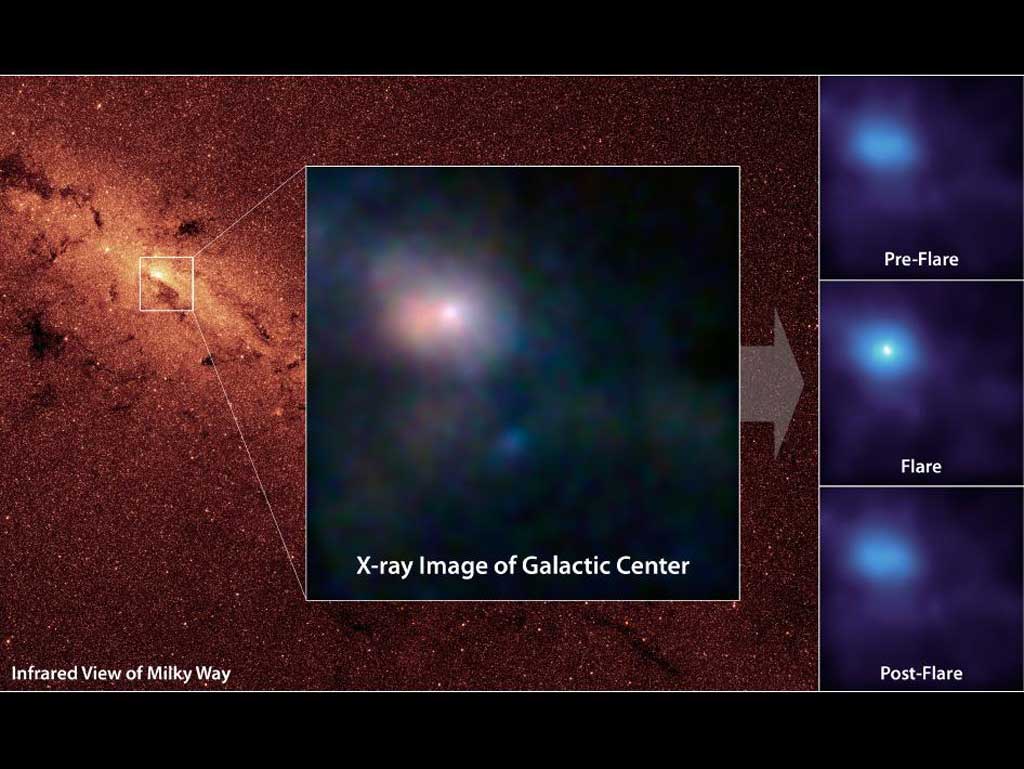

NuSTAR, launched June 13, is the only telescope capable of producing focused images of the highest-energy X-rays. For two days in July, the telescope teamed up with other observatories to observe Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*), the black hole at the center of the Milky Way. Participating telescopes included NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory, which sees lower-energy X-ray light, and the W. M. Keck Observatory atop Mauna Kea in Hawaii, which took infrared images.

Compared to giant black holes at the centers of other galaxies, Sgr A* is relatively quiet. Active black holes tend to gobble up stars and other fuel around them. Sgr A* is thought only to nibble or not eat at all, a process that is not fully understood. When black holes consume fuel — whether a star, a gas cloud, or, as recent Chandra observations have suggested, even an asteroid — they erupt with extra energy.

In the case of NuSTAR, its state-of-the-art telescope is picking up X-rays emitted by consumed matter being heated up to about 180 million degrees Fahrenheit (100 million degrees Celsius) and originating from regions where particles are boosted close to the speed of light. Astronomers say these NuSTAR data, when combined with the simultaneous observations taken at other wavelengths, will help them better understand the physics of how black holes snack and grow in size.

“Astronomers have long speculated that the black hole’s snacking should produce copious hard X-rays, but NuSTAR is the first telescope with sufficient sensitivity to actually detect them,” said Chuck Hailey of Columbia University in New York City.