New results from NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope have revealed a rare example of a type Ia explosion in which a dead star “fed” off an aging star like a cosmic zombie, triggering a blast. The results help researchers piece together how these powerful and diverse events occur.

“It’s kind of like being a detective,” said Brian Williams of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “We look for clues in the remains to try to figure out what happened, even though we weren’t there to see it.”

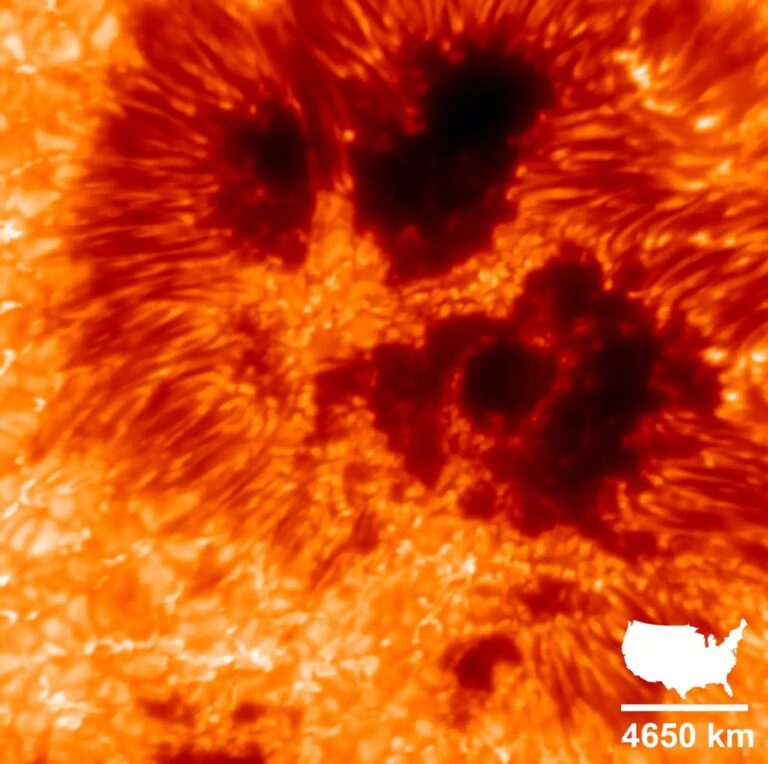

Supernovae are essential factories in the cosmos, churning out heavy metals, including the iron contained in our blood. Type Ia supernovae tend to blow up in consistent ways and thus have been used for decades to help scientists study the size and expansion of our universe. Researchers say that these events occur when white dwarfs — the burnt-out corpses of stars like our Sun — explode.

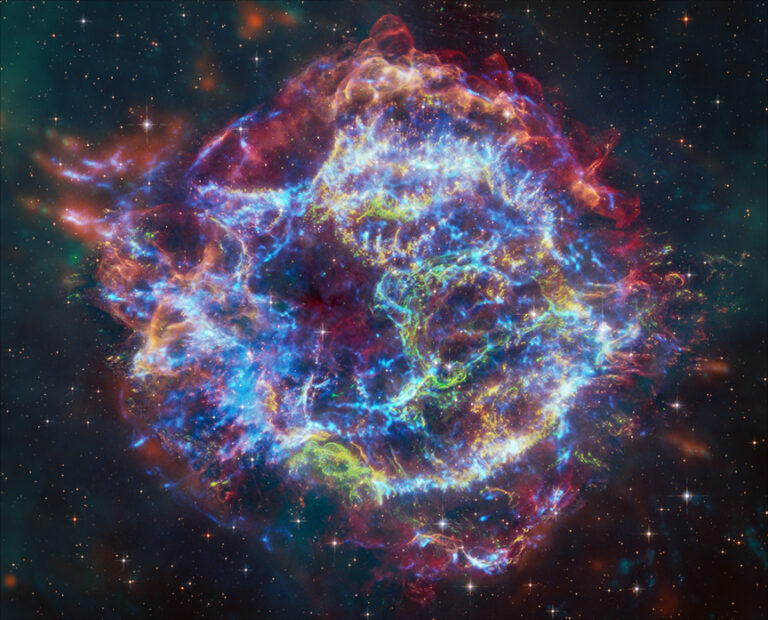

Evidence has been mounting over the past 10 years that the explosions are triggered when two orbiting white dwarfs collide — with one notable exception. Kepler’s supernova, named after the astronomer Johannes Kepler who witnessed it along with many other people in 1604, is thought to have been preceded by just one white dwarf and an elderly companion star called a red giant. Scientists know this because the remnant sits in a pool of gas and dust shed by the aging star.

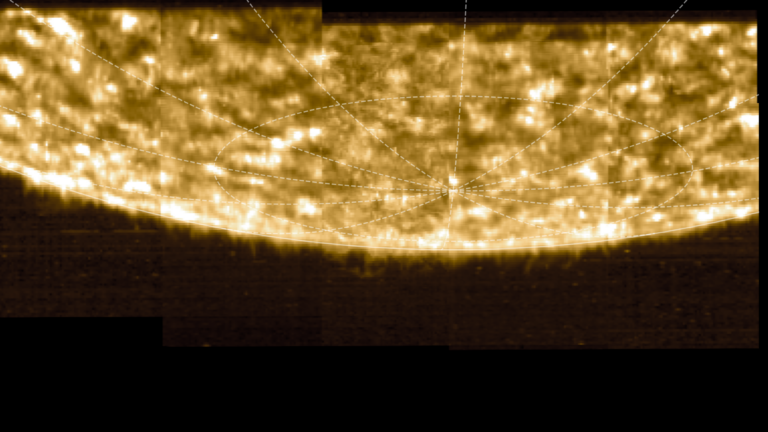

Spitzer’s new observations now find a second case of a supernova remnant resembling Kepler’s. Called N103B, the roughly 1,000-year-old supernova remnant lies 160,000 light-years away in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a small galaxy near our Milky Way.

“It’s like Kepler’s older cousin,” said Williams. He explained that N103B, though somewhat older than Kepler’s supernova remnant, also lies in a cloud of gas and dust thought to have been blown off by an older companion star. “The region around the remnant is extraordinarily dense,” he said. Unlike Kepler’s supernova remnant, no historical sightings of the explosion that created N103B are recorded.

Both the Kepler and N103B explosions are thought to have unfolded as follows: An aging star orbits its companion — a white dwarf. As the aging star molts, which is typical for older stars, the shed material falls onto the white dwarf. This causes the white dwarf to build up in mass, become unstable, and explode.

According to the researchers, this scenario may be rare. While the pairing of white dwarfs and red giants was thought to underlie virtually all type Ia supernovae as recently as a decade ago, scientists now think that collisions between two white dwarfs are the most common cause. The new Spitzer research highlights the complexity of these tremendous explosions and the variety of their triggers. The case of what makes a dead star rupture is still very much an unsolved mystery.