A team of astronomers from Germany, Bulgaria, and Poland has used a completely new technique to find an exotic extrasolar planet. The same approach is sensitive enough to find planets as small as Earth in orbit around other stars. The group, led by Gracjan Maciejewski of Jena University in Germany, used transit timing variation (TTV) to detect a planet with 15 times the mass of Earth in the system WASP-3, 700 light-years from the Sun in the constellation Lyra.

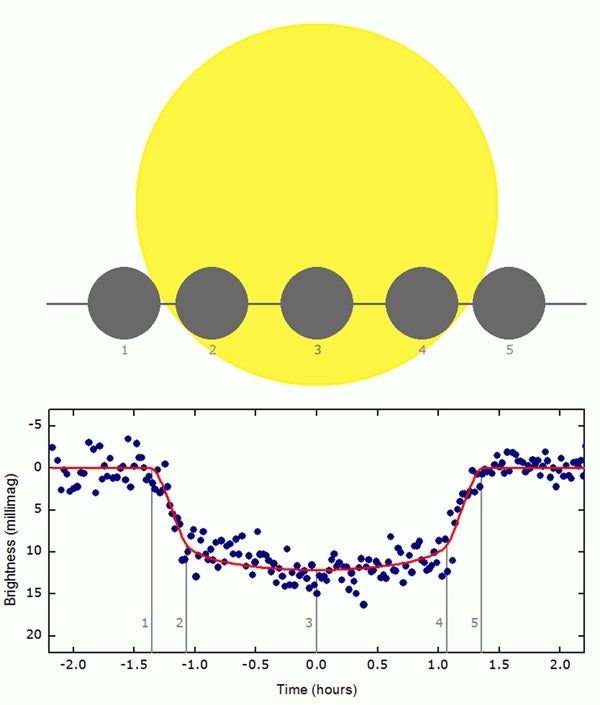

TTV was suggested as a new technique for discovering planets a few years ago. Transits take place when a planet moves in front of the star it orbits, temporarily blocking some of the light from the star. So far this method has been used to detect a number of planets and is being deployed by the Kepler and Corot space missions in its search for planets similar to Earth.

If a planet — typically large — is found, then the gravity of additional smaller planets will tug on the larger object, causing deviations in the regular cycle of transits. The TTV technique compares the deviations with predictions made by extensive computer-based calculations, allowing astronomers to deduce the makeup of the planetary system.

For this search, the team used the 35-inch (90 cm) telescope of the University Observatory Jena and the 24-inch (60 cm) telescope of the Rohzen National Astronomical Observatory in Bulgaria to study transits of WASP-3b, a large planet with 630 times the mass of Earth.

“We detected periodic variations in the transit timing of WASP-3b. These variations can be explained by an additional planet in the system with a mass of 15 Earth-mass — one Uranus mass — and a period of 3.75 days,” said Maciejewski.

“In line with international rules, we called this new planet WASP-3c,” said Maciejewski. This newly discovered planet is among the least massive planets known to date and also the least massive planet known orbiting a star that is more massive than our Sun.

This is the first time that a new extrasolar planet has been discovered using this method. The new TTV approach is an indirect detection technique like the previously successful transit method.

The discovery of the second 15 Earth-mass planet makes the WASP-3 system very intriguing. The new planet appears to be trapped in an external orbit, twice as long as the orbit of the more massive planet. Such a configuration is probably a result of the early evolution of the system.

The TTV method is very attractive because it is particularly sensitive to small perturbing planets, even down to the mass of Earth. For example, an Earth-mass planet will pull on a typical gas giant planet orbiting close to its star and cause deviations in the timing of the larger objects’ transits of up to 1 minute.

This is a big enough effect to be detected with relatively small 3-foot (1 meter) diameter telescopes, and discoveries can be followed up with larger instruments. The team is now using the 33-foot (10 meters) Hobby-Eberly Telescope in Texas to study WASP-3c in more detail.