The voyage of NASA’s Pluto-bound New Horizons spacecraft through the Jupiter system earlier this year provided a bird’s-eye view of a dynamic planet that has changed since the last close-up looks by NASA spacecraft.

New Horizons passed Jupiter on February 28, riding the planet’s gravity to boost its speed and shave three years off its trip to Pluto. It was the eighth spacecraft to visit Jupiter — but a combination of trajectory, timing and technology allowed it to explore details no probe had seen before, such as lightning near the planet’s poles, the life cycle of fresh ammonia clouds, boulder-size clumps speeding through the planet’s faint rings, the structure inside volcanic eruptions on its moon Io, and the path of charged particles traversing the previously unexplored length of the planet’s long magnetic tail.

“The Jupiter encounter was successful beyond our wildest dreams,” says New Horizons Principal Investigator Alan Stern, of NASA Headquarters, Washington. “Not only did it prove out our spacecraft and put it on course to reach Pluto in 2015, it was a chance for us to take sophisticated instruments to places in the Jovian system where other spacecraft couldn’t go, and to return important data that adds tremendously to our understanding of the solar system’s largest planet and its moons, rings and atmosphere.”

The New Horizons team presents its latest and most detailed analyses of that data today at the American Astronomical Society’s Division for Planetary Sciences meeting in Orlando, Florida, and in a special section of the October 12 issue of the journal Science. The section includes nine technical papers written by New Horizons team members and collaborators.

From January through June, New Horizons’ seven science instruments made

More than 700 separate observations of the Jovian system — twice the activity planned at Pluto — with most of them coming in the eight days around closest approach to Jupiter. “We carefully selected observations that complemented previous missions, so that we could focus on outstanding scientific issues that needed further investigation,” says New Horizons Jupiter Science Team Leader Jeff Moore, of NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, California. “The Jupiter system is constantly changing and New Horizons was in the right place at the right time to see some exciting developments.”

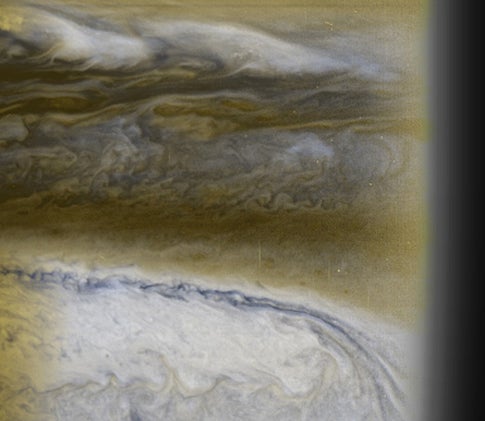

Jovian weather was high on the list, as New Horizons’ visible light, infrared and ultraviolet remote-sensing instruments probed Jupiter’s atmosphere for data on cloud structure and composition. They saw clouds form from ammonia welling up from the lower atmosphere and heat-induced lighting strikes in the polar regions — the first polar lighting ever observed beyond Earth, demonstrating that heat moves through water clouds at virtually all latitudes across Jupiter. They made the first most detailed size and speed measurements yet of “waves” that run the width of planet and indicate violent storm activity below. Additionally, New Horizons snapped the first close-up images of the Little Red Spot, a nascent storm about half the size of Jupiter’s larger Great Red Spot and about 70 percent of Earth’s diameter, gathering new information on storm dynamics.

Under a range of lighting and viewing angles, New Horizons also captured the clearest images ever of the tenuous Jovian ring system. In them, scientists spotted clumps of debris that may indicate a recent impact inside the rings, or some more exotic phenomenon; movies made from New Horizons images also offer an unprecedented look at ring dynamics, with the tiny inner moons Metis and Adrastea shepherding the materials around the rings. A search for smaller moons inside the rings — and possible new sources of the dusty material — found no bodies wider than a kilometer.

The mission’s investigations of Jupiter’s four largest moons focused on Io, the closest to Jupiter and whose active volcanoes blast tons of material into the Jovian magnetosphere (and beyond). New Horizons spied 11 different volcanic plumes of varying size, three of which were seen for the first time and one — a spectacular 200-mile-high eruption rising above the volcano Tvashtar — that offered an unprecedented opportunity to trace the structure and motion of the plume as it condensed at high altitude and fell back to the moon’s surface. In addition, New Horizons spotted the infrared glow from at least 36 Io volcanoes, and measured lava temperatures up to 1,900 degrees Fahrenheit, similar to many terrestrial volcanoes.

New Horizons’ global map of Io’s surface backs the moon’s status as the solar system’s most active body, showing more than 20 geological changes since the Galileo Jupiter orbiter provided the last close-up look in 2001. The remote imagers also kept watch on Io in the darkness of Jupiter’s shadow, noting mysterious glowing gas clouds above dozens of volcanoes. Scientists suspect that this gas helps to resupply Io’s atmosphere.

New Horizons’ flight down Jupiter’s magnetotail gave it an unprecedented look at the vast region dominated by the planet’s strong magnetic field. Looking specifically at the fluxes of charged particles that flow hundreds of millions of miles beyond the giant planet, the New Horizons particle detectors saw evidence that tons of material from Io’s volcanoes move down the tail in large, dense, slow-moving blobs. By analyzing the observed variations in particle fluxes over a wide range of energies and scales, New Horizons scientists are exploring how the volcanic gases from Io are ionized, trapped and energized by Jupiter’s magnetic field, then ultimately ejected from the system.

Designed, built and operated by the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland, New Horizons lifted off from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Florida, in January 2006. The fastest spacecraft ever launched, it needed just 13 months to reach Jupiter. New Horizons is now about halfway between the orbits of Jupiter and Saturn, more than 743 million miles (1.19 billion kilometers) from Earth. It will fly past Pluto and its moons in July 2015 before heading deeper into the Kuiper belt of icy rocky objects on the planetary frontier.