The radar system on the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Mars Express has uncovered new details about some of the most mysterious deposits on Mars: The Medusae Fossae Formation. It has given the first direct measurement of the depth and electrical properties of these materials, providing new clues about their origin.

The Medusae Fossae Formation (MFF) are deposits on Mars that are both unique and enigmatic. Found near the equator, along the divide between the highlands and lowlands, they may represent some of the youngest deposits on the surface of the planet. This is inferred from the marked lack of impact craters dotting this terrain, unlike on older terrain.

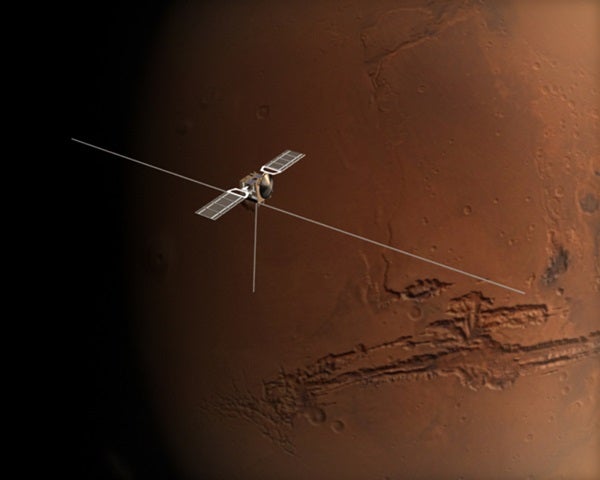

Mars Express has been collecting data from this region using its Mars Advanced Radar for Subsurface and Ionospheric Sounding (MARSIS). Between March 2006 and April 2007, Mars Express orbited the region many times, taking radar soundings as it went.

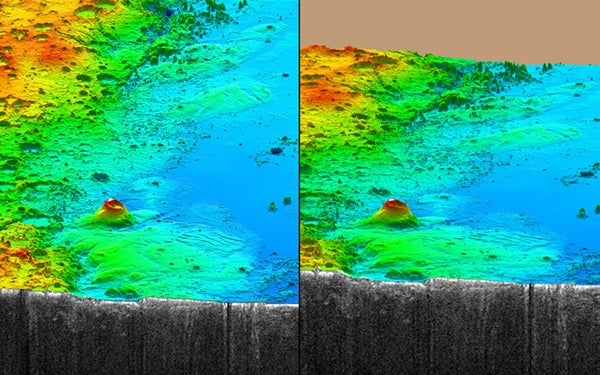

For the first time, these radar soundings revealed the depth of the MFF layers, because of the time it took for the radar beam to pass through the top layers and bounce off the solid rock beneath. “We didn’t know just how thick the MFF deposits really were,” said Thomas Watters, lead author of the results at the Center for Earth and Planetary Studies, National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution, USA. “Some investigators thought they might be a thin veneer overlaying topographic rises in the lowlands. The new data show that the MFF are massive deposits over 2.5 kilometers thick in some places where MARSIS orbits pass over them,” Watters added.

The MFF deposits intrigue scientists because they are associated with regions that absorb certain wavelengths of Earth-based radar. This had led to them being called ‘stealth’ regions because they give no radar echo. The affected wavelengths are 3.5 to 12.6 centimeters. MARSIS, however, works at wavelengths of 50 to over 100 meters. At these wavelengths, the radar waves mostly pass through the MFF deposits creating subsurface echoes when the radar signal reflects off the plains material beneath.

Deciding between these scenarios is not easy, even with the new data. The MARSIS data reveal the electrical properties of the layers. These suggest that the layers could be poorly packed, fluffy or dusty material. However it is difficult to understand how porous material from wind-blown dust can be kilometers thick and yet not be compacted under the weight of the overlying material.

On the other hand, although the electrical properties are consistent with water ice layers, there is no other strong evidence for the presence of ice today in the equatorial regions of Mars.

“If there is water ice at the equator of Mars, it must be buried at least several meters below the surface,” says Jeffrey Plaut, MARSIS Co-Principal Investigator at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, USA. This is because the water vapor pressure on Mars is so low that any ice near the surface would quickly evaporate. “It is still early in the game. We may get cleverer with our analysis and interpretation or we may only know when we go there with a drill and see for ourselves,” says Plaut.

Giovanni Picardi at the University of Rome, La Sapienza, Principal Investigator of the experiment, says, “Not only is MARSIS providing excellent scientific results but the team is also working on the processing techniques that will allow for more accurate evaluation of the characteristics of the subsurface layers and their constituent material. Hence, the possible extension of the mission will be very important to increase the number of observations over the regions of interest and improve the accuracy of the evaluations.”