Key Takeaways:

The findings show that the stellar explosion took place in a hollowed-out cavity, allowing material expelled by the star to travel much faster and farther than it would have otherwise.

“This supernova remnant got really big, really fast,” said Brian J. Williams from North Carolina State University in Raleigh. “It’s two to three times bigger than we would expect for a supernova that was witnessed exploding nearly 2,000 years ago. Now, we’ve been able to finally pinpoint the cause.”

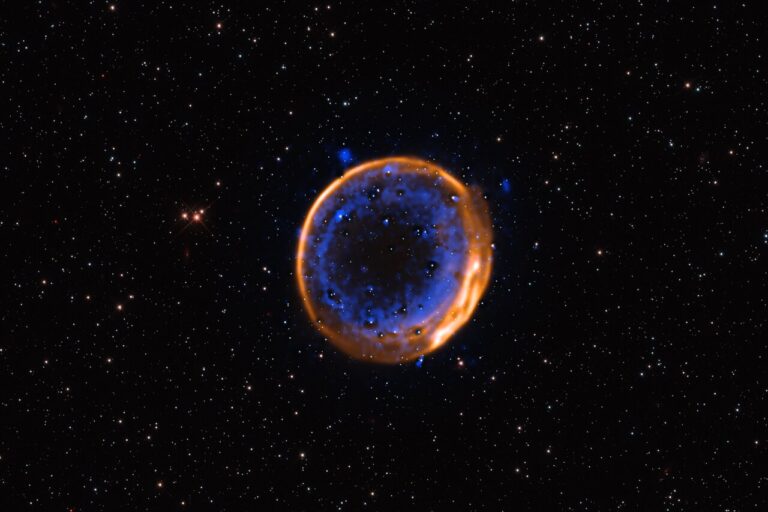

In A.D. 185, Chinese astronomers noted a “guest star” that mysteriously appeared in the sky and stayed for about eight months. By the 1960s, scientists had determined that the mysterious object was the first documented supernova. Later, they pinpointed RCW 86 as a supernova remnant located about 8,000 light-years away. But a puzzle persisted. The star’s spherical remains are larger than expected. If they could be seen in the sky today in infrared light, they’d take up more space than our Moon.

The solution arrived through new infrared observations made with Spitzer and WISE and previous data from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and the European Space Agency’s XMM-Newton Observatory.

The findings reveal that the event is a type Ia supernova created by the relatively peaceful death of a star like our Sun, which then shrank into a dense star called a white dwarf. The white dwarf is thought to have later blown up in a supernova after siphoning matter, or fuel, from a nearby star.

“A white dwarf is like a smoking cinder from a burnt-out fire,”

Williams said. “If you pour gasoline on it, it will explode.”

The observations also show for the first time that a white dwarf can create a cavity around it before blowing up in a type Ia event. A cavity would explain why the remains of RCW 86 are so big. When the explosion occurred, the ejected material would have traveled unimpeded by gas and dust and spread out quickly.

Spitzer and WISE allowed the team to measure the temperature of the dust making up the RCW 86 remnant at about –325° degrees Fahrenheit (–200° Celsius). They then calculated how much gas must be present within the remnant to heat the dust to those temperatures. The results point to a low-density environment for much of the life of the remnant, essentially a cavity.

Scientists initially suspected that RCW 86 was the result of a core-collapse supernova, the most powerful type of stellar blast. They had seen hints of a cavity around the remnant, and, at that time, such cavities were only associated with core-collapse supernovae. In those events, massive stars blow material away from them before they blow up, carving out holes around them.

But other evidence argued against a core-collapse supernova. X-ray data from Chandra and XMM-Newton indicated that the object consisted of high amounts of iron, a telltale sign of a type Ia blast. Together with the infrared observations, a picture of a type Ia explosion into a cavity emerged.

“Modern astronomers unveiled one secret of a two-millennia-old cosmic mystery only to reveal another,” said Bill Danchi from NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C. “Now, with multiple observatories extending our senses in space, we can fully appreciate the remarkable physics behind this star’s death throes, yet still be as in awe of the cosmos as the ancient astronomers.”

The findings show that the stellar explosion took place in a hollowed-out cavity, allowing material expelled by the star to travel much faster and farther than it would have otherwise.

“This supernova remnant got really big, really fast,” said Brian J. Williams from North Carolina State University in Raleigh. “It’s two to three times bigger than we would expect for a supernova that was witnessed exploding nearly 2,000 years ago. Now, we’ve been able to finally pinpoint the cause.”

In A.D. 185, Chinese astronomers noted a “guest star” that mysteriously appeared in the sky and stayed for about eight months. By the 1960s, scientists had determined that the mysterious object was the first documented supernova. Later, they pinpointed RCW 86 as a supernova remnant located about 8,000 light-years away. But a puzzle persisted. The star’s spherical remains are larger than expected. If they could be seen in the sky today in infrared light, they’d take up more space than our Moon.

The solution arrived through new infrared observations made with Spitzer and WISE and previous data from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and the European Space Agency’s XMM-Newton Observatory.

The findings reveal that the event is a type Ia supernova created by the relatively peaceful death of a star like our Sun, which then shrank into a dense star called a white dwarf. The white dwarf is thought to have later blown up in a supernova after siphoning matter, or fuel, from a nearby star.

“A white dwarf is like a smoking cinder from a burnt-out fire,”

Williams said. “If you pour gasoline on it, it will explode.”

The observations also show for the first time that a white dwarf can create a cavity around it before blowing up in a type Ia event. A cavity would explain why the remains of RCW 86 are so big. When the explosion occurred, the ejected material would have traveled unimpeded by gas and dust and spread out quickly.

Spitzer and WISE allowed the team to measure the temperature of the dust making up the RCW 86 remnant at about –325° degrees Fahrenheit (–200° Celsius). They then calculated how much gas must be present within the remnant to heat the dust to those temperatures. The results point to a low-density environment for much of the life of the remnant, essentially a cavity.

Scientists initially suspected that RCW 86 was the result of a core-collapse supernova, the most powerful type of stellar blast. They had seen hints of a cavity around the remnant, and, at that time, such cavities were only associated with core-collapse supernovae. In those events, massive stars blow material away from them before they blow up, carving out holes around them.

But other evidence argued against a core-collapse supernova. X-ray data from Chandra and XMM-Newton indicated that the object consisted of high amounts of iron, a telltale sign of a type Ia blast. Together with the infrared observations, a picture of a type Ia explosion into a cavity emerged.

“Modern astronomers unveiled one secret of a two-millennia-old cosmic mystery only to reveal another,” said Bill Danchi from NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C. “Now, with multiple observatories extending our senses in space, we can fully appreciate the remarkable physics behind this star’s death throes, yet still be as in awe of the cosmos as the ancient astronomers.”