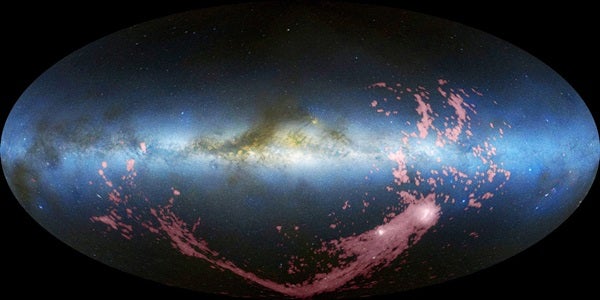

The Magellanic Stream is an arc of hydrogen gas spanning more than 100° of the sky as it trails behind the Milky Way’s neighbor galaxies, the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds. Our home galaxy, the Milky Way, has long been thought to be the dominant gravitational force in forming the Stream by pulling gas from the Magellanic Clouds. A new computer simulation by Gurtina Besla from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and her colleagues now shows that the Magellanic Stream resulted from a past close encounter between these dwarf galaxies rather than effects of the Milky Way.

“The traditional models required the Magellanic Clouds to complete an orbit about the Milky Way in less than 2 billion years in order for the Stream to form,” said Besla. Other work by Besla and her colleagues, and measurements from the Hubble Space Telescope by a colleague, rule out such an orbit, however, and suggest the Magellanic Clouds are new arrivals and not longtime satellites of the Milky Way.

This creates a problem: How can the Stream have formed without a complete orbit about the Milky Way?

To address this, Besla and her team set up a simulation assuming the Magellanic Clouds were a stable binary system on their first passage about the Milky Way in order to show how the Stream could form without relying on a close encounter with the Milky Way.

The team postulated that the Magellanic Stream and Bridge are similar to bridge and tail structures seen in other interacting galaxies and formed before the Milky Way captured the Magellanic Clouds.

“While the Clouds didn’t actually collide,” said Besla, “they came close enough that the Large Cloud pulled large amounts of hydrogen gas away from the Small Cloud. This tidal interaction gave rise to the Bridge we see between the Clouds, as well as the Stream.”

“We believe our model illustrates that dwarf-dwarf galaxy tidal interactions are a powerful mechanism to change the shape of dwarf galaxies without the need for repeated interactions with a massive host galaxy like the Milky Way,” said Besla.

While the Milky Way may not have drawn the Stream material out of the Magellanic Clouds, the Milky Way’s gravity now shapes the orbit of the Clouds and thereby controls the appearance of the tail.

“We can tell this from the line-of-sight velocities and spatial location of the tail observed in the Stream today,” said Lars Hernquist from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.