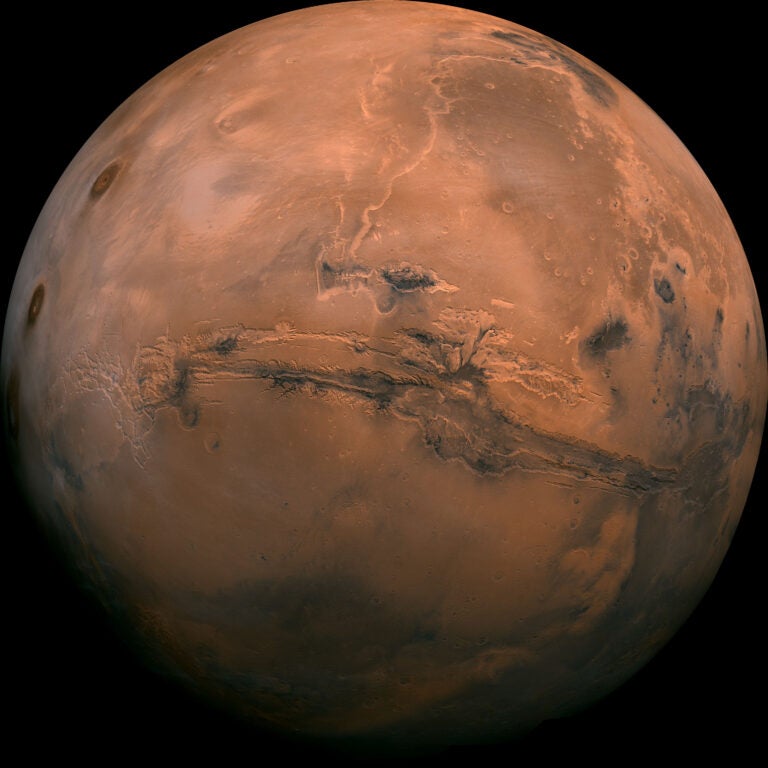

Closer to home, the prime targets this month are Mars and Mercury. The Red Planet hovers above the southwestern horizon in early evening; its bright orange-red light is sure to grab your attention. Mercury comes up before the Sun in early November for its best morning appearance of 2014 for northern observers.

Our tour of solar system objects begins in the southwestern sky as darkness falls. Mars lingers on these November evenings, setting more than three hours after the Sun and seeming to maintain its altitude from one night to the next. But appearances can be deceiving — Mars actually gains altitude this month. The planet moves eastward relative to the background stars almost as quickly as the Sun does, so its angular separation from our star stays nearly constant. The overriding factor this month is that Mars slides to a position more above the Sun, placing it slightly farther above the horizon.

The Red Planet shines at magnitude 1.0 and is the brightest point of light in the southwestern sky. Some of the fainter background objects make good companions, however. On November 3, Mars passes 0.6° north of 3rd-magnitude Lambda (λ) Sagittarii, the star at the apex of Sagittarius’ conspicuous Teapot asterism. The Lagoon Nebula (M8) then lies 5° west and globular cluster M22 just 2° east-northeast of the planet. Mars moves to within 1° of M22 on November 5 and 6.

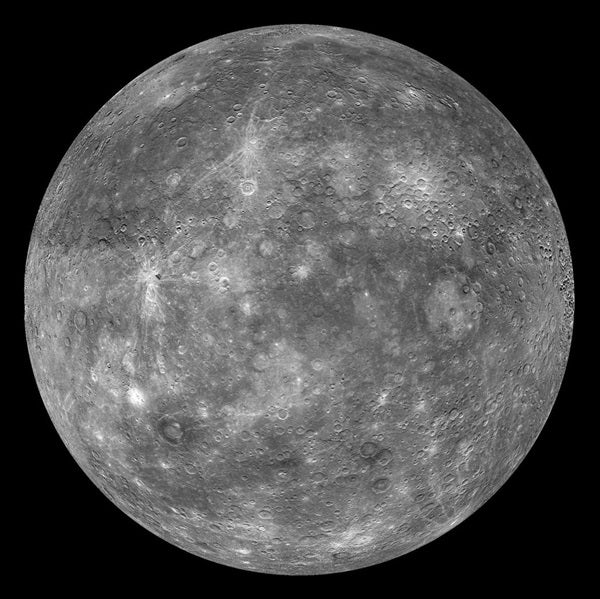

Mars’ rapid eastward trek continues through November; by the 30th, it stands 20° from Lambda Sgr. Unfortunately, a planet typically moves fastest when it lies on the opposite side of the Sun from Earth. Mars now resides more than 150 million miles away and appears through a telescope as a featureless disk 5″ across.

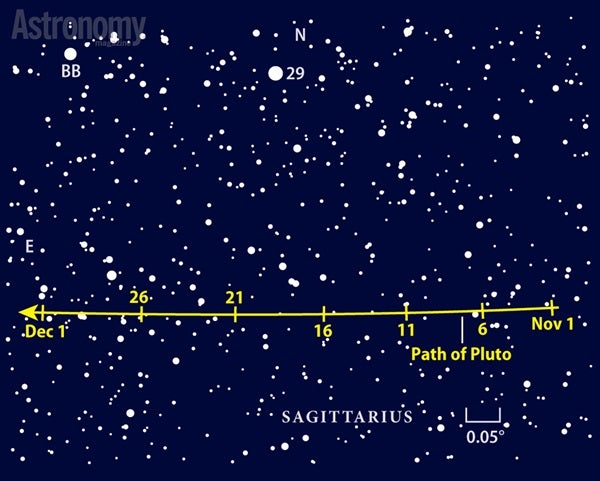

The easiest way to find Pluto is to offset from 5th-magnitude 29 Sgr. The solar system object passes 22′ due south of this star November 19. The finder chart below will help you get to the right area, but the best way to confirm a sighting is to return to the same field a night or two later and identify the “star” that moved.

In contrast to Mars, Neptune barely budges this month. It reaches its stationary point November 16, when its westward motion comes to a halt and it starts moving to the east. Couple this with the outer planet’s typically slow progress, and you have a recipe for immobility. Neptune remains 0.9° west of magnitude 4.8 Sigma (σ) Aquarii all month.

The planet glows at magnitude 7.9, so you’ll need binoculars or a telescope to spot it. Here’s an easy way. Head out shortly after darkness falls, and find the Great Square of Pegasus high in the south. Pick out 2nd-magnitude Markab (Alpha [α] Pegasi), which marks the square’s lower right corner, and then Fomalhaut, the lone 1st-magnitude star above the southern horizon. These two objects are 45° apart, and midway between them is 4th-magnitude Lambda Aqr. Another 4th-magnitude sun, Tau (τ) Aqr, lies 6° due south of Lambda. Sigma is the western vertex of an equilateral triangle with this pair. Once you’ve located Neptune west of Sigma, turn a telescope on the planet to see its 2.3″-diameter disk.

Magnitude 5.7 Uranus reached opposition and peak visibility in October, and it remains a tempting target nearly all night. The planet stands halfway between the southeastern horizon and the zenith after sunset and is easy to track down through binoculars. Let Epsilon (ε) and Delta (δ) Piscium, a pair of 4th-magnitude suns in the constellation Pisces the Fish, be your guides. These two lie about a dozen degrees southeast of Algenib (Gamma [γ] Pegasi), the star at the Great Square’s lower left corner. Look 2.3° due south of Delta (the more westerly of the pair) for 6th-magnitude 96 Psc. Uranus spends November within 1° of this star, passing due south of it at midmonth.

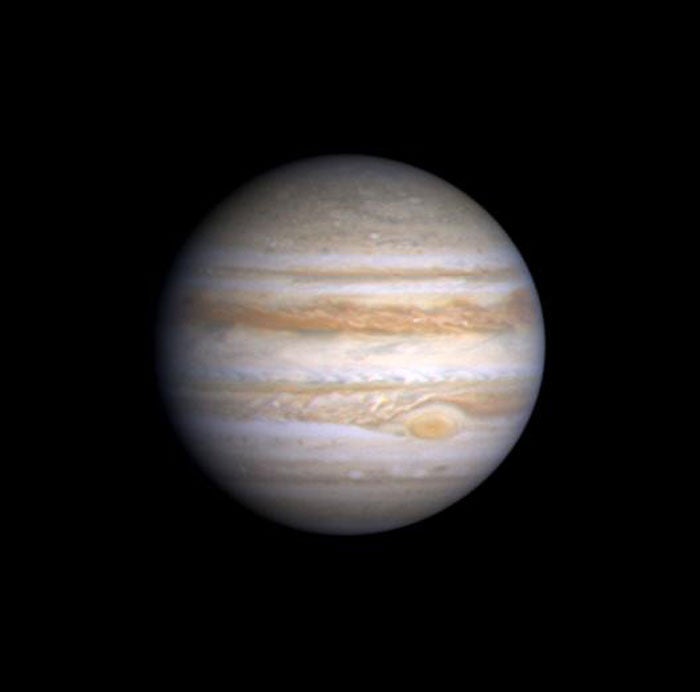

Jupiter rises around midnight local time November 1 and two hours earlier by month’s end. This world shines at magnitude –2.1, far outshining the background stars of its host constellation, Leo the Lion. The planet moves eastward relative to this backdrop during November, and by the 30th closes to within 8° of the Lion’s luminary, 1st-magnitude Regulus.

Although Jupiter shows up easily to naked eyes even when it is close to the horizon, the best views through a telescope come once it climbs higher a couple of hours later. Turbulence in Earth’s atmosphere often blurs close-up views of objects, particularly those at low altitudes.

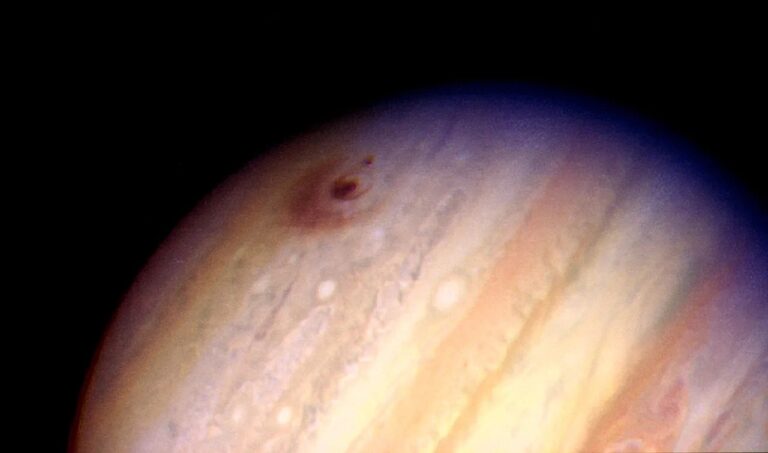

Jupiter’s equatorial diameter grows from 36″ to 40″ during November. At this size, small scopes will show quite a lot of detail in the gas giant’s cloud tops. Expect to see two parallel dark belts sandwiching a brighter zone coinciding with the planet’s equator. Under steady viewing conditions, a series of alternating belts and zones comes into focus.

Don’t let the view of Jupiter distract you from the equally intriguing targets that lie right beside it. The planet’s four bright moons put on a show every night, changing positions noticeably within a few hours as they orbit the central giant. Adding to the excitement is Earth’s passage through the moons’ orbital plane, an event that happens only twice during Jupiter’s 12-year sojourn around the Sun. This alignment produces mutual satellite events — occultations, when one moon passes in front of another, and eclipses, when one passes into another’s shadow. The series lasts through next August.

November 23 brings another exciting event as Io occults Europa at Jupiter’s eastern limb (though the planet’s glow makes observing this event difficult). Europa peeks out from behind Jupiter’s disk at 2:16 a.m. EST — just as Io starts to occult it. One minute later, Io begins to transit Jupiter, and two minutes after that, the mutual occultation ends.

As Jupiter climbs high in the southeast before dawn in early November, Mercury pops into view near the horizon. The innermost planet reaches greatest elongation on the 1st, when it lies 19° west of the Sun and rises about 90 minutes before our star. It appears about 10° high 45 minutes before sunrise, which makes this the elusive planet’s best morning appearance of the year.

If you scan the area through binoculars, you should glimpse Spica, Virgo’s brightest star, to Mercury’s lower right. The planet passes 5° north of Spica on the 3rd. Mercury shines at magnitude –0.6, some five times brighter than the 1st-magnitude star. Although Spica climbs higher with each passing day, Mercury dips lower, and you’ll have a hard time spotting it after mid-November.

A telescope shows Mercury’s changing size and phase quite nicely. On the 1st, the planet appears 6.9″ across and slightly more than half-lit. A week later, it spans 5.9″ and reveals a three-quarters-lit phase. And by midmonth, the diminutive world’s 5.3″-diameter disk is 91 percent illuminated.

Venus and Saturn lie too close to the Sun in our sky to see in November. Both will return next month — the former will hang low in the evening sky while the latter will climb higher before dawn.

Early sunsets and long nights are hallmarks of November. For planetary and deep-sky aficionados who brave the cool temperatures, this provides extra observing time. But Moon watchers gain as well. Viewers can study the waning gibbous Moon in midevening, tracking the terminator (the dividing line between day and night) as it sweeps westward, and still get to bed on time. With sunlight hitting the Moon’s surface from the west instead of the east as it does during waxing phases, it casts Luna’s terrain in a different light.

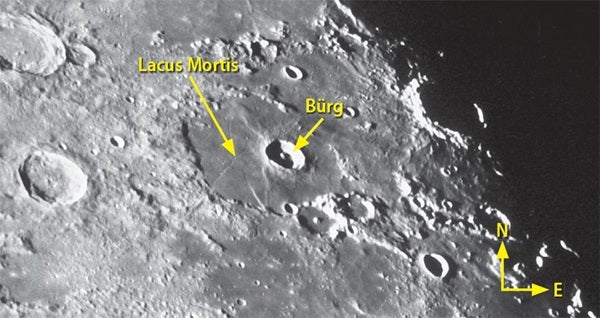

On the evening of November 11, lunar night is about to overtake Lacus Mortis (the Lake of Death) and the prominent crater Bürg that lies inside. (The view approximates that in the photo at right.) The lengths of the shadows provide our eyes and brains with cues that allow us to judge the heights of features. Note that little remains of Lacus Mortis’ eastern wall, but the rather jumbled block of higher ground to the west casts nice shadows. Innumerable impacts over the eons ejected the material that forms this rough terrain. Lava later welled up through the floor of Lacus Mortis and provided a clean slate for future hits.

Bürg is a 25-mile-wide crater that displays the classic features of a relatively young impact scar: a raised rim with a single central peak. It’s big enough that gravity caused the interior of the steep walls to “slump” and create a relatively simple terrace. The two craters along Lacus Mortis’ edge south of Bürg have battered rims worn down by long-term bombardment — a sure sign of advanced age.

After rigor mortis froze the lava plains of Lacus Mortis in place, the Moon continued to churn underneath, leaving a fascinating set of fractures. To the west of Bürg is a rille (channel) that formed as terrain pulled apart. The scarp (cliff) south of this rille came into being as the ground to the west dropped down. Another rille stands immediately east of this scarp.

All these features show up best when the Sun lies just above the lunar horizon, so they may not be visible on the 10th. Don’t worry if clouds block your view on the 11th, however — you can see this area again when sunrise returns on the 27th. By then, Luna will be a 5-day-old waxing crescent, resplendent with a magnificent stretch of features along the terminator.

The Leonid meteor shower peaks on the North American afternoon of November 17. Observers under dark skies should see up to 15 meteors per hour on the mornings of both the 17th and 18th. But this rate is really just an educated guess. Viewers have witnessed intriguing variations during the past several years.

Fortunately, the waning crescent Moon won’t scatter much unwanted light during the prime viewing hours after midnight. The radiant lies in the Sickle asterism of Leo the Lion, which climbs nearly overhead before dawn. Because Leonid meteors arrive nearly head-on from the direction of Earth’s orbital motion, they hit our atmosphere at the highest rate possible — some 44 miles per second. To learn more about the shower, see “A great year for the Leonids” on p. 60.

| WHEN TO VIEW THE PLANETS |

||

| Evening Sky |

Midnight | Morning Sky |

| Mars (southwest) |

Jupiter (east) |

Mercury (east) |

| Uranus (southeast) |

Uranus (southwest) |

Jupiter (south) |

| Neptune (south) |

Neptune (west) |

|

| |

|

|

| |

||

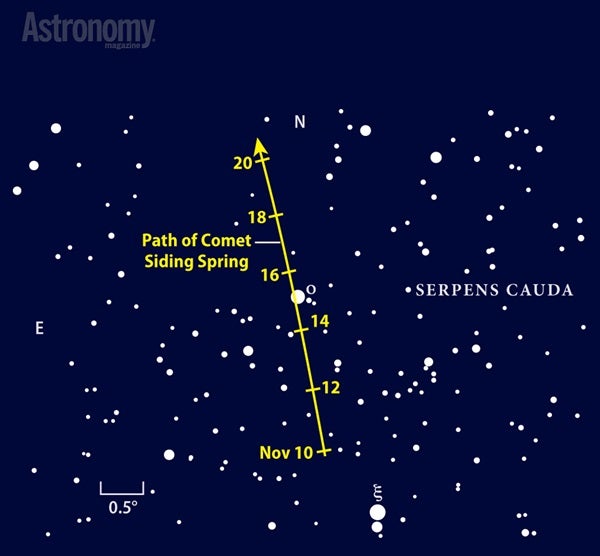

If only we could have been martians in October. On the 19th, we would have had a once-in-a-lifetime experience watching Comet Siding Spring (C/2013 A1) pass just 81,000 miles away. We earthlings get a consolation prize this month — seeing the same comet without the need for a spacesuit helmet. Comet Siding Spring should glow at 9th magnitude in November’s early evening sky.

The best views will come under a dark sky after the Moon exits the stage around the 10th. A 4-inch telescope at low power will catch the out-of-round fuzzball if you look for it before it drops close to the horizon around 7:30 p.m. The comet spends November climbing northward through Serpens the Serpent and Ophiuchus the Serpent-bearer. On the 15th, Siding Spring will be easy to get to but tough to see, possibly lost in the glare from 4th-magnitude Omicron (ο) Serpentis.

Globular star cluster M72 in Aquarius — located 45° east of the comet — is comparable in brightness and apparent size. Pump your scope’s power past 100x to see the differences. Siding Spring’s light appears softer and should have a bright point in the middle, the latter trait a result of heightened activity because the comet just passed closest to the Sun. This so-called false nucleus is a dense dust shroud that hides the true surface. The comet’s southwestern flank should appear more sharply defined than the opposite side, where a stubby tail fans away from the Sun.

Observers close to or south of the equator also can enjoy 6th-magnitude Comet PANSTARRS (C/2012 K1). It lies near magnitude –0.7 Canopus early this month and passes magnitude 0.5 Achernar around November 22’s New Moon.

Reaching out, touching, and understanding are all aspects of the human condition we engage in while stargazing. Each dot of light that touches our eyes carries with it a story. For example, watching one such dot change position from night to night announces the presence of a small cog in our solar system’s machinery.

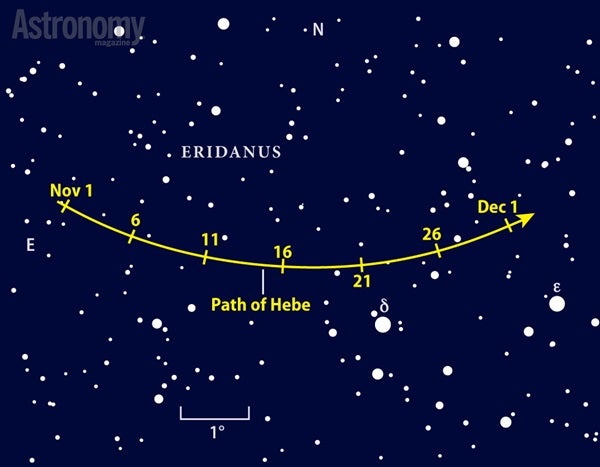

In the case of asteroid 6 Hebe, we’re seeing one of the hundreds of thousands of cogs that inhabit the space between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. This 118-mile-wide rock appears to be boating down Eridanus the River, visible in the southeast in midevening. Use 4th-magnitude Delta (δ) and Epsilon (ε) Eridani as your guides to rediscover German astronomer Karl Hencke’s 1847 find. The asteroid peaks at magnitude 8.0 around its November 15 opposition, but it is probably easiest to find on the 21st and 22nd when it passes only 1° north of Delta.

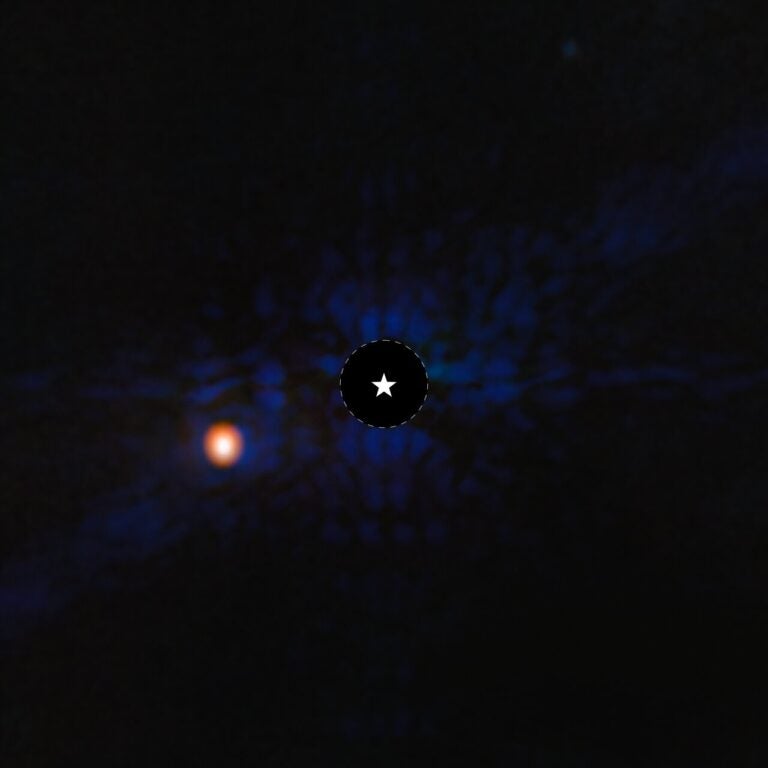

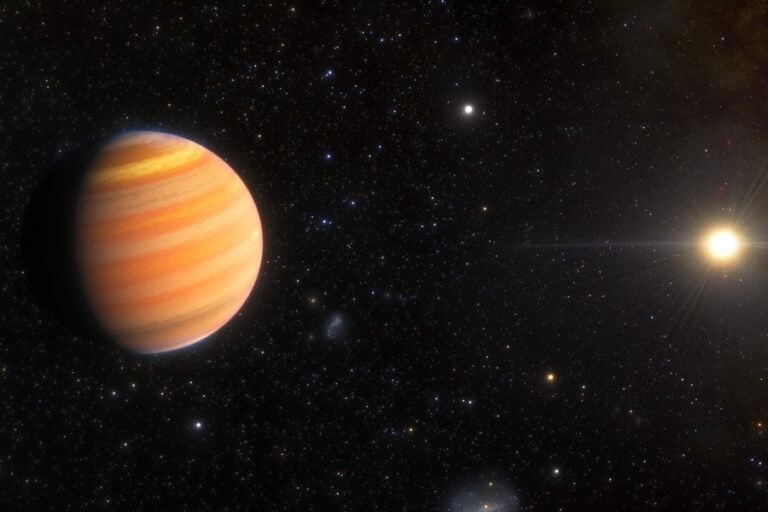

The name Epsilon Eridani may sound familiar because it fires the imaginations of scientists and writers as a potential abode of life. Younger and slightly cooler than the Sun, it lies just 10.5 light-years away. Astronomers have discovered a planet of some 1.55 Jupiter masses circling this star in a seven-year orbit. Pause at this star and ponder the possibilities of an Enceladus or Europa-like moon around the invisible giant as the light touches your eye.

Martin Ratcliffe provides planetarium development for Sky-Skan, Inc. from his home in Wichita, Kansas. Meteorologist Alister Ling works for Environment Canada in Edmonton, Alberta.