The dramatic differences between the northern and southern hemispheres of Mars have puzzled scientists for 30 years. One of the proposed explanations — a massive asteroid impact — now has strong support from computer simulations carried out by two groups of researchers. Planetary scientists at the University of California, Santa Cruz, were involved in both studies, which appear in the June 26 issue of Nature.

“It’s a very old idea, but nobody had done the numerical calculations to see what would happen when a big asteroid hits Mars,” says Francis Nimmo, associate professor of Earth and planetary sciences at UCSC and first author of one of the papers.

Nimmo’s group found that such an impact could indeed produce the observed differences between the martian hemispheres. The other study used a different approach and reached the same conclusion. Nimmo’s paper also suggests testable predictions about the consequences of the impact.

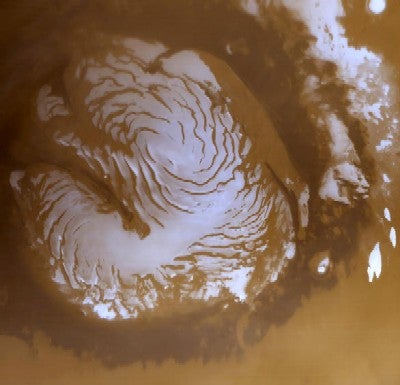

The so-called hemispheric dichotomy was first observed by NASA’s Viking missions to Mars in the 1970s. The Viking spacecraft revealed that the two halves of the planet look very different, with relatively young, low-lying plains in the north and relatively old, cratered highlands in the south. Some 20 years later, the Mars Global Surveyor mission showed that the crust of the planet is much thicker in the south and also revealed magnetic anomalies present in the southern hemisphere and not in the north.

“Two main explanations have been proposed for the hemispheric dichotomy — either some kind of internal process that changed one half of the planet, or a big impact hitting one side of it,” Nimmo says. “The impact would have to be big enough to blast the crust off half of the planet, but not so big that it melts everything. We showed that you really can form the dichotomy that way.”

The quantitative model used by Nimmo’s group calculated the effects of an impact in two dimensions. Asphaug’s group used a different model to calculate impacts in three dimensions, but with lower resolution (i.e., less detail in the simulation).

“The two approaches are very complementary; putting them together gives you a complete picture,” Nimmo says. “The two-dimensional model provides high resolution, but you can only look at vertical impacts. The three-dimensional model allows nonvertical impacts, but the resolution is lower so you can’t track what happens to the crust.”

Most planetary impacts are not head-on, Asphaug says. His group found a “sweet spot” of impact conditions that result in a hemispheric dichotomy matching the observations. Those conditions include an impactor about one-half to two-thirds the size of the Moon, striking at an angle of 30 to 60°.

“This is how planets finish their business of formation,” Asphaug says. “They collide with other bodies of comparable size in gargantuan collisions. The last of those big collisions defines the planet.”

According to Nimmo’s analysis, shock waves from the impact would travel through the planet and disrupt the crust on the other side, causing changes in the magnetic field recorded there. The predicted changes are consistent with observations of magnetic anomalies in the southern hemisphere, he says.

In addition, new crust that formed in the northern lowlands would be derived from deep mantle rock melted by the impact and should have significantly different characteristics from the southern hemisphere crust. Certain Martian meteorites may have originated from the northern crust, Nimmo says. The study also suggests that the impact occurred around the same time as the impact on Earth that created the Moon.

Nimmo’s group includes UCSC graduate student Shawn Hart, associate researcher Don Korycansky, and Craig Agnor of Queen Mary University, London. The other paper is by Margarita Marinova and Oded Aharonson of the California Institute of Technology and Erik Asphaug, professor of Earth and planetary sciences at UCSC.