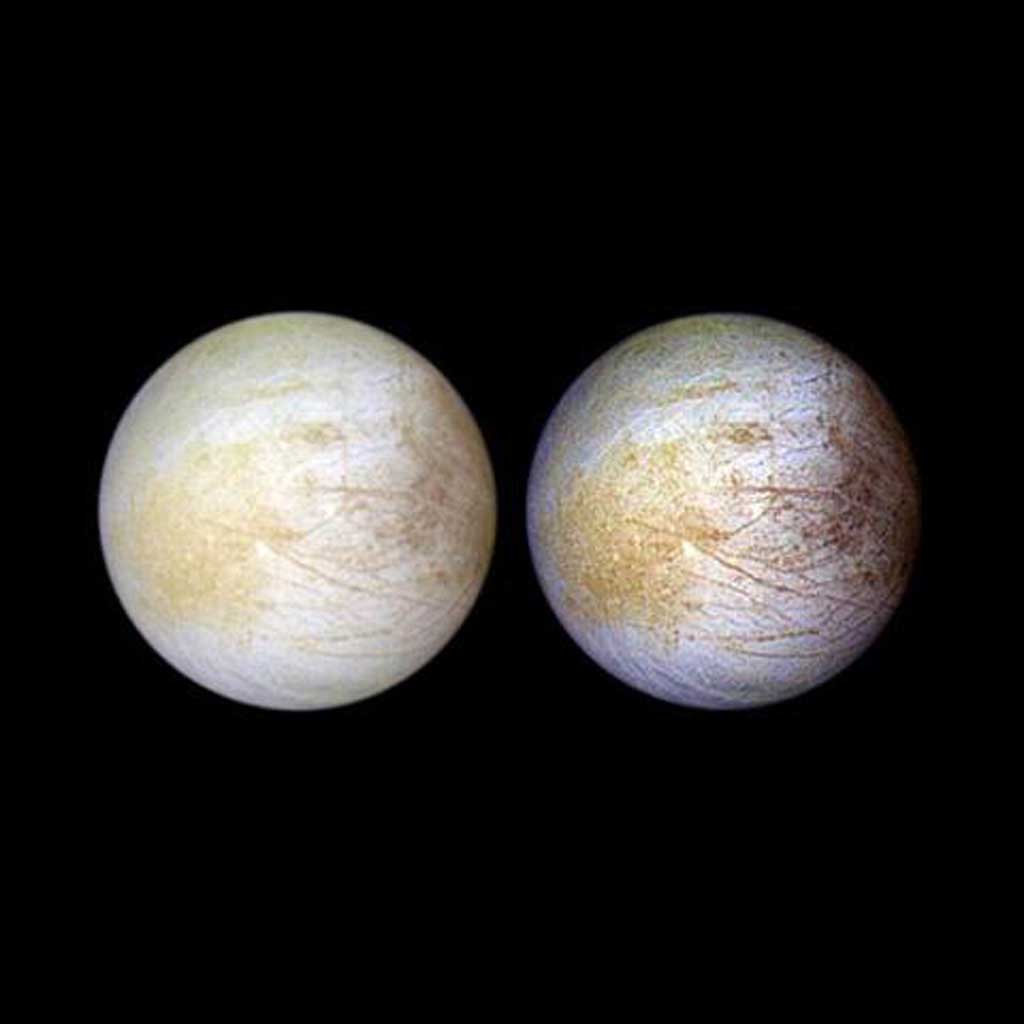

By analyzing the distinctive cracks lining the icy face of Europa, NASA scientists found evidence that this moon of Jupiter likely spun around a tilted axis at some point.

“One of the mysteries of Europa is why the orientations of the long, straight cracks called lineaments have changed over time. It turns out that a small tilt, or obliquity, in the spin axis, sometime in the past, can explain a lot of what we see,” said Alyssa Rhoden at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

Europa’s network of crisscrossing cracks serves as a record of the stresses caused by massive tides in the moon’s global ocean. These tides occur because Europa travels around Jupiter in a slightly oval-shaped orbit. When Europa comes closer to the planet, the moon gets stretched like a rubber band, with the ocean height at the long ends rising nearly 100 feet (30 meters). That’s roughly as high as the 2004 tsunami in the Indian Ocean, but it happens on a body that measures only about one-quarter of Earth’s diameter. When Europa moves farther from Jupiter, it relaxes back into the shape of a ball.

The moon’s ice layer has to stretch and flex to accommodate these changes, but when the stresses become too great, it cracks. The puzzling part is why the cracks in Europa’s icy layer point in different directions over time, even though the same side of Europa always faces Jupiter.

A leading explanation has been that Europa’s frozen outer shell might rotate slightly faster than the moon orbits Jupiter. If this out-of-sync rotation does occur, the same part of the ice shell would not always face Jupiter.

Rhoden and her Goddard co-author Terry Hurford put that idea to the test using images taken by NASA’s Galileo spacecraft during its nearly eight-year mission, which began in 1995. “Galileo produced many paradigm shifts in our understanding of Europa, one of which was the phenomena of out-of-sync rotation,” said Claudia Alexander of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

Rhoden and Hurford compared the pattern of cracks in a key area near Europa’s equator to predictions based on three different explanations. The first set of predictions was based on the rotation of the ice shell. The second set assumed that Europa was spinning around a tilted axis, which, in turn, made the orientation of the pole change over time. This effect, called precession, looks very much like what happens when a spinning toy top has started to slow down and wobble. The third explanation was that the cracks were laid out in random directions.

The researchers got the best performance when they assumed that precession had occurred, caused by a tilt of about 1°, and combined this effect with some random cracks, said Rhoden. Out-of-sync rotation was surprisingly unsuccessful, in part, because Rhoden found an oversight in the original calculations for this model.

The results are compelling enough to satisfy Richard Greenberg, the professor from the University of Arizona, Tucson, who had earlier proposed the idea of out-of sync rotation.

“By extracting new information from the Galileo data, this work refines and improves our understanding of the very unusual geology of Europa,” said Greenberg, who was Rhoden’s undergraduate advisor and Hurford’s graduate advisor.

The existence of tilt would not rule out the out-of-sync rotation, according to Rhoden and Greenberg. But it does suggest that Europa’s cracks may be much more recent than previously thought. That’s because the spin pole direction may change by as much as a few degrees per day, completing one precession period over several months. On the other hand, with the leading explanation, one full rotation of the ice sheet would take roughly 250,000 years. In either case, several rotations would be needed to explain the crack patterns.

A tilt also could affect the estimates of the age of Europa’s ocean. Tidal forces are thought to generate the heat that keeps Europa’s ocean liquid, and a tilt in the spin axis might suggest that tital forces generate more heat. This heat might keep the ocean liquid longer.

The analysis does not specify when the tilt would have occurred. So far, measurements have not been made of the tilt of Europa’s axis, and this is one goal scientists have for any future Europa mission.

“One of the fascinating open questions is how active Europa still is. If researchers pin down Europa’s current spin axis, then our findings would allow us to assess whether the clues we are finding on the moon’s surface are consistent with the present-day conditions,” said Rhoden.