Now all that is over. No way around it, the end of a great adventure is bitter.

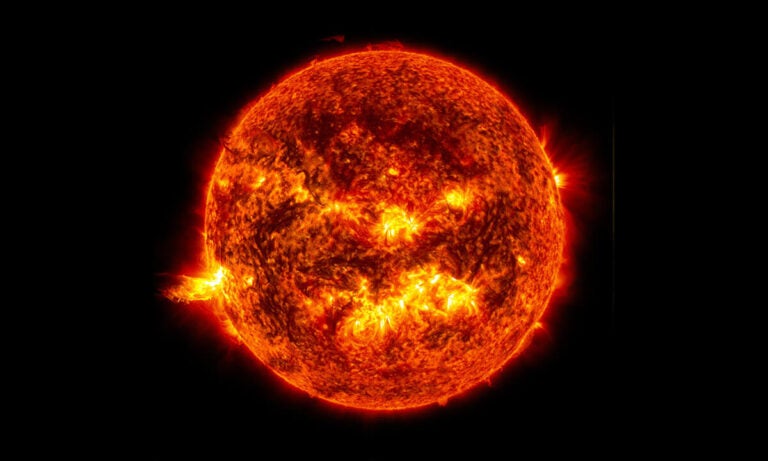

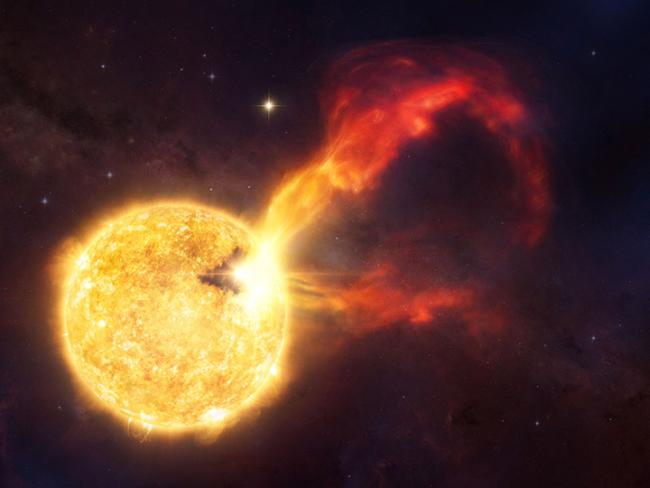

The sweet part is the extraordinary science Rosetta has conducted along the way. Early results confirmed the presence of diverse organic compounds; showed that comets alone could not have provided the water that fills Earth’s oceans; mapped the surprisingly complex magnetic environment around Comet 67P; and catalogued enormous eruptions of gas and dust–roughly 100,000 kilos [200,000 pounds] at a time–that show how comets disintegrate under the force of solar heat. Much of Rosetta’s dataset has yet to be fully analyzed. Planetary scientists will be mining new insights from it for many years to come.

The time and effort that went into the Rosetta mission only intensify the bitter and the sweet. Planning for the mission began in 1985, when the mission was known as CNSR, for “Comet Nucleus Sample Return.” Many things changed along the way as budgets shrank, NASA dropped out as a partner with the European Space Agency (ESA), and the whole idea of bringing home samples of the comet had to be abandoned. (I discuss the mission’s twisted history in more detail here.) Even after launch in 2004, Rosetta needed more than 10 years to reach the comet. That is the longest gap ever between launch and arrival for a space probe, longer even than New Horizon’s 9-year journey to Pluto.

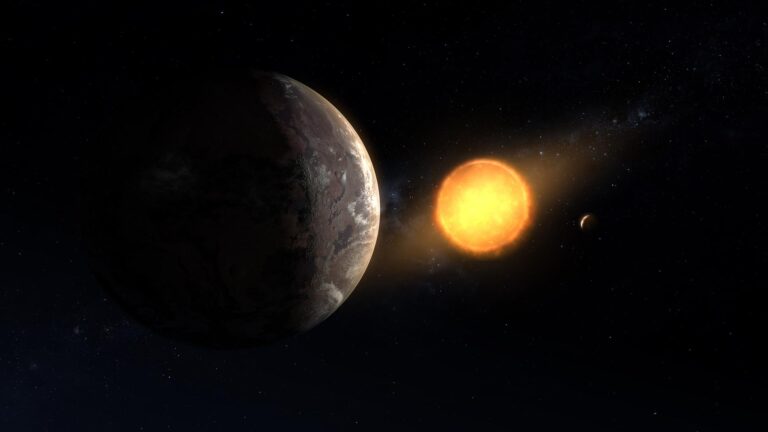

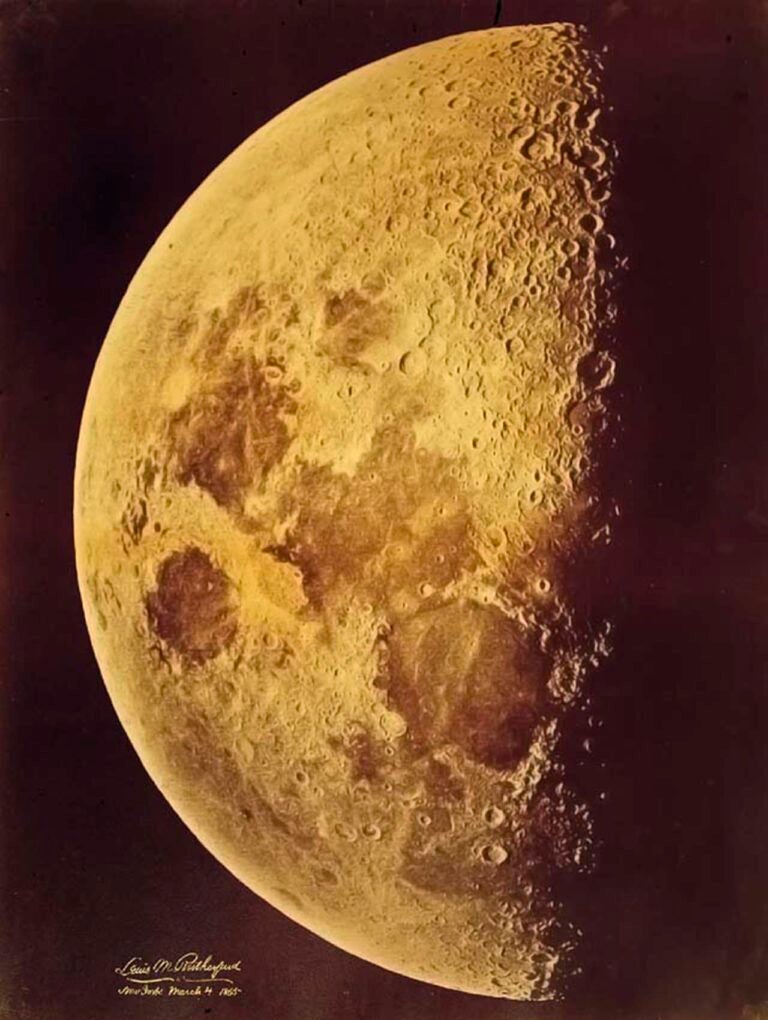

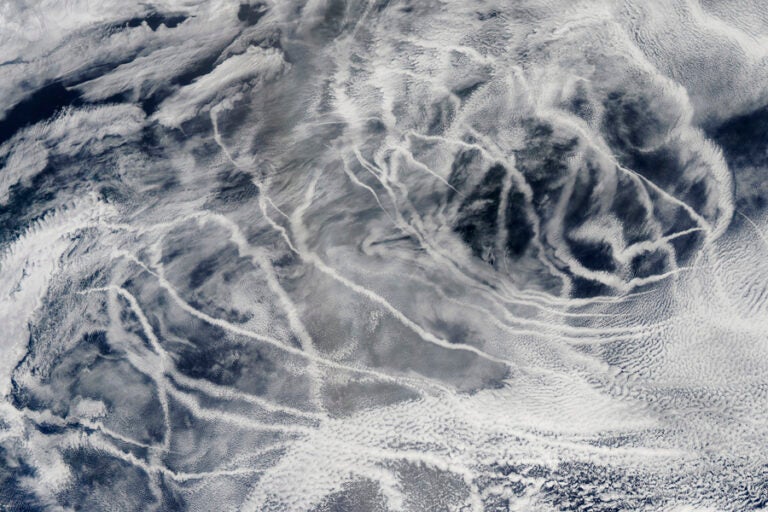

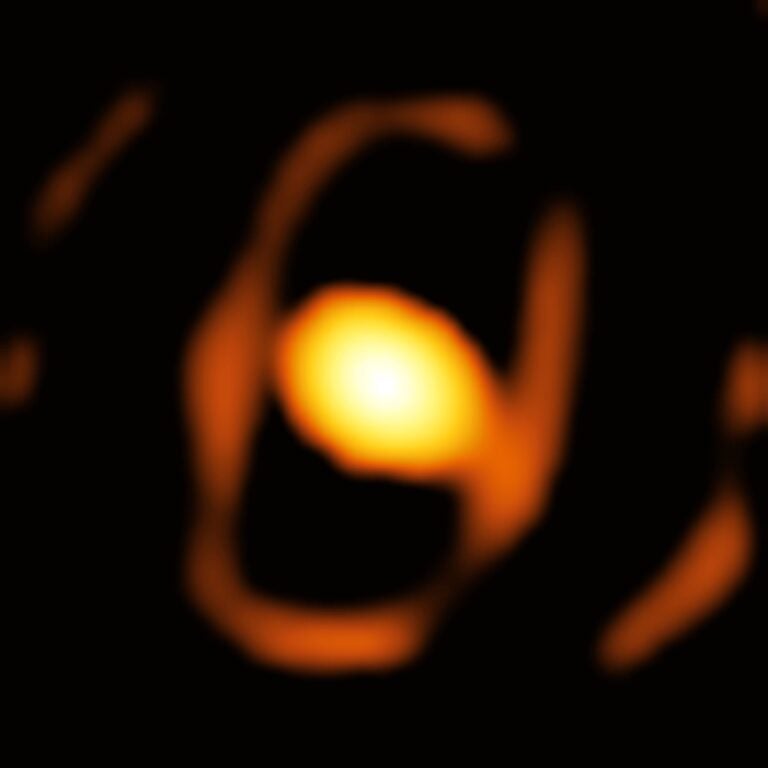

The payoff from this drawn-out timeline is that Rosetta saw remarkable sights along the way. Its two-year main mission lasted so long that the ESA described it as “living with a comet.” The agency created a series of affecting cartoon animations that anthropomorphized the spacecraft in a way that greatly amplified the “living” aspect. And then there are the astonishing images that Rosetta has returned. The spacecraft is dead, but the emotional power of these views, along with their perception-altering qualities, insure that they will live forever as milestones in the human exploration of the solar system.

For more space news and images, follow me on Twitter: @coreyspowell