Key Takeaways:

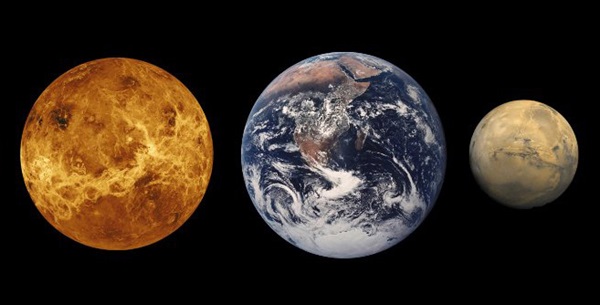

Dr. Kevin Walsh, a research scientist at Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), led an international team performing simulations of the early solar system, demonstrating how an infant Jupiter may have migrated to within 1.5 astronomical units (AU, the distance from the Sun to the Earth) of the Sun, stripping a lot of material from the region and essentially starving Mars of formation materials.

“If Jupiter had moved inwards from its birthplace down to 1.5 AU from the Sun, and then turned around when Saturn formed as other models suggest, eventually migrating outwards towards its current location, it would have truncated the distribution of solids in the inner solar system at about 1 AU and explained the small mass of Mars,” says Walsh. “The problem was whether the inward and outward migration of Jupiter through the 2 to 4 AU region could be compatible with the existence of the asteroid belt today, in this same region. So, we started to do a huge number of simulations.

“The result was fantastic,” says Walsh. “Our simulations not only showed that the migration of Jupiter was consistent with the existence of the asteroid belt, but also explained properties of the belt never understood before.”

The asteroid belt is populated with two very different types of rubble, very dry bodies as well as water-rich orbs similar to comets. Walsh and collaborators showed that the passage of Jupiter depleted and then re-populated the asteroid belt region with inner-belt bodies originating between 1 and 3 AU as well as outer-belt bodies originating between and beyond the giant planets, producing the significant compositional differences existing today across the belt.

Dr. Kevin Walsh, a research scientist at Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), led an international team performing simulations of the early solar system, demonstrating how an infant Jupiter may have migrated to within 1.5 astronomical units (AU, the distance from the Sun to the Earth) of the Sun, stripping a lot of material from the region and essentially starving Mars of formation materials.

“If Jupiter had moved inwards from its birthplace down to 1.5 AU from the Sun, and then turned around when Saturn formed as other models suggest, eventually migrating outwards towards its current location, it would have truncated the distribution of solids in the inner solar system at about 1 AU and explained the small mass of Mars,” says Walsh. “The problem was whether the inward and outward migration of Jupiter through the 2 to 4 AU region could be compatible with the existence of the asteroid belt today, in this same region. So, we started to do a huge number of simulations.

“The result was fantastic,” says Walsh. “Our simulations not only showed that the migration of Jupiter was consistent with the existence of the asteroid belt, but also explained properties of the belt never understood before.”

The asteroid belt is populated with two very different types of rubble, very dry bodies as well as water-rich orbs similar to comets. Walsh and collaborators showed that the passage of Jupiter depleted and then re-populated the asteroid belt region with inner-belt bodies originating between 1 and 3 AU as well as outer-belt bodies originating between and beyond the giant planets, producing the significant compositional differences existing today across the belt.